By Erin Weinman, Reader Services

I recently came across the Elizabeth Craft White diary, written in 1770 when the death of her husband left her distraught. “Life seems a burden to me since Death, Cruel, & unrelenting Death- has snacht from me the Partner of my heart: O fated Death how could you come, tho he called for thee why did you not pass by him, turn from him & flee away.” Elizabeth White’s diary lasted from December 26, 1770 until its sudden end on January 23, 1771. Throughout its passages, she questions the fate of her husband’s soul and laments over the ultimate fate of her own soul. The entries read more of a reflection of her own spiritual awareness as she makes it clear that she has accepted death’s presence and hopes that her daughter would be properly guided into heaven.

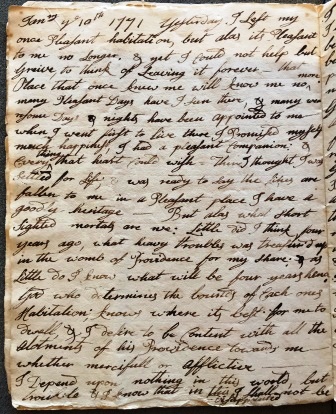

“Jan ye 10th 1771”

The diary is heartbreaking, but Elizabeth White’s thoughts were not uncommon during a period in which mourning became intertwined with religious culture. In early Massachusetts, it wasn’t uncommon for people to use the death of a loved one as a time to reflect upon their own souls and ask God to forgive their sins, faced with the reality that their own end could be near. Ministers often encouraged their parishioners to keep diaries to embellish their faith in Heaven, viewing this as another way to become closer to God and to understand what death meant. Sermons often revolved around the topic of dying, such as Timothy Edwards’ All the living must surely die, and go to judgement.

Man is born to trouble as the Sparks fly upward tears sorrow & Death is the Portion of every person that is Born into the world. I have been born, most certainly & it is as certain that I must die & I know not how soon. Die I must! & die I shall! (Elizabeth White, January 18, 1771).

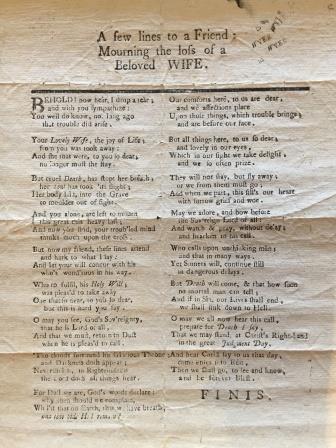

While Elizabeth White would live another 60 years, her words reflected those of many others who faced the prospect of death. While writing a diary was certainly a way to privately grieve and bring routine back into one’s life, the sentimentality can be found in countless other accounts. Public displays of mourning were common through sermons and poetry, much of which told personal stories to illustrate the importance of accepting our demise. In an undated poem titled A few lines to a Friend: Mourning the loss of a Beloved Wife, the author clearly states the purpose of a loved one’s death is to remember our own mortality.

“A few lines to a Friend: Mourning the loss of a Beloved WIFE,” n.d.

“O may we all now heart his call,

Prepare for Death I say,

That we may stand, at Christ’s Right-hand

In the great Judgement Day.

And hear Christ say to us that day,

Come enter into Reît,

Then we shall go, to see and know,

And be forever Blest.”

Such expressions were also common in letters of correspondence. In a Letter from William and Mary Pepperrell to their children, the Pepperrell’s express a similar sentiment at the death of their son.

Your kind & symathiseing Letter of this day we received for wich are oblig’d to you and as you justly observe that if this Great affliction may be wich we have meet with in ye Death of our Dear Son may be sancthifyed so as to warn our hearts from our Earthly Enjoyments & to set them more & more upon our Great Creator […]

As the living hoped to reflect upon death, there was also importance placed upon a person’s final words. Tracts were commonly produced to teach people of the importance of dying properly and to share examples of good Christians, such as The Triumphant Christian: or The dying words and extraordinary behavior of a gentleman. Rev. Mr. Clarke later wrote in 1756 The real Christians hope in death, or, An account of the edifying behavior of several persons of piety in their last moments. The resting words of young children and women were of particular interest and were commonly published for the public to learn from. This model became embedded in New England culture. Dying words reflected one’s entire life. To speak such proper final words meant that one had led a pious life and was ready to accept their fate. It meant they would make amends with any sin they had caused and reassured those close by that they were off to heaven.

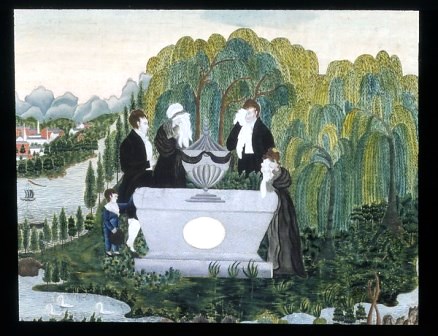

Mourning Picture, ca. 1810. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

To die quietly or without any resting words often caused distress to the living. Oftentimes, many would suspect that silence meant the person led a sinful life and that their fate was eternity in Hell. Elizabeth White’s husband died quietly after succumbing to fever, leaving her to question his fate.

When I think of home it seems to hurt me, once I had a home but now I have none. O that it was with me as in time past- But alas I shall never see a good day, more in the Land of the Living, once I was a girl then was I happy; once I was a married woman & was very happy till it Pleased the Lord to visit the pasture of my joys & cares, with a violent likeness that; deprived him of his senses so that he was never himself not long together to his dying day- now alas he is gone from whence he will never return, even to the Land of darkness, & ye shadow of death: a Land of darkness, as darkness itself & of ye shadow of death without any order- if he had died upon a sick bed, I should have some Peace concerning him: but now I have none- he is gone, I know not how it is with him […]

Such a prescribed mentality towards death is found across hundreds of letters and diaries, but they certainly don’t discredit the sentimentality of the writer’s feelings. It is simply part of human nature to cope with tragedy. In a society where religion played a vital role in everyday life, it is not at all surprising that death became a lesson to remind oneself of their ultimate ending.

To see what other related materials are held are at the Society, try searching our online catalog, ABIGAIL, then consider Visiting the Library.

Sources:

Seeman, Eric R. “’She died like good old Jacob’: deathbed scenes and inversions of power in New England, 1675-1775.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, v. 104 (1994), p. 285-314.

Vinovskis, Maris. “Angels’ heads and weeping willows: death in early America.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, v. 86, pt. 2 (1977), p. 273-302.