By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

“The Russian People pass their lives in a continual and alternate succession of feasting and fasting,” John Quincy Adams stated to his mother without so much as a salutation. From his vantage point as minister plenipotentiary to St. Petersburg in 1811, Adams wrote to his parents about Russian politics, court life, and traditions. Based on the eight pages he dedicated to it, one of the customs that intrigued John Quincy most was how Russians celebrated Easter.

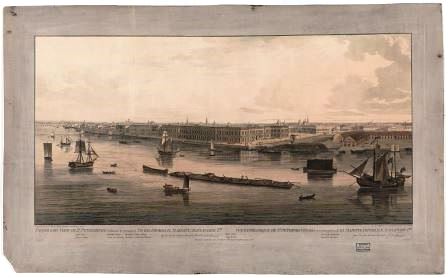

Panaromic view of St. Petersburg by J. A. Atkinson, c.1807.(Library of Congress)

In mid-February seven weeks of “rigorous lent” began during which believers should eat “absolutely nothing but bread and salt.” John Quincy acknowledged that the severity of the restrictions were somewhat abated in practice, and that “among the highest class of the nobility there are persons not extremely scrupulous about observing the fast at-all.” This laxity came at a price, however, as the public was severely critical of those who did not follow the orders of the Church. For this reason, “there are few even of the highest ranks, but choose to be thought regular in their practice.” He added that the Imperial family was “punctilious in setting the example.”

Besides being without the foods to which they were accustomed, theaters were closed for all seven weeks of Lent. “No entertainments are given, and the families which profess to be scrupulous in their duties neither pay nor receive visits.” In place of the usual merriments, there were religious services three or four times a week. In the last week of lent, called “Passion-week,” there were ceremonies every day.

On Good Friday, funeral processions led into churches where elaborate representations of Christ’s sepulcher were erected and lit until the midnight services on Easter morning. At the stroke of midnight, cannons were fired to signal the start of three- or four-hour services in all the churches of St. Petersburg.

As a foreign minister, John Quincy was permitted to attend services in the chapel in the Imperial palace. He arrived at the palace “in full dress as to Court” and was ushered into the chapel just before midnight. He soon heard the thunder of cannons and observed Emperor Alexander I and the Imperial family process into the candlelit chapel. Attendants distributed lit wax tapers as the all-male choir performed. At the conclusion of the Mass, seven priests formed a line before the Emperor, each holding a holy relic. The Emperor kissed each relic and “embraced the Priests themselves.” John Quincy wrote that the other members of the Imperial family followed in succession, “excepting that the Priests instead of being embraced by the Ladies, kiss’d their hands.” He informed Abigail that this was a new trend with which many believers from all ranks of society were displeased because it removed the “primitive equality of all Christian believers” and “the purity of Christian innocence” from the tradition. He writes that many preferred “the good old smack upon the cheek and lips, which they boast of as having always been given at Easter.” Interestingly, John Quincy noted, “Every individual in the chapel. . .was understood to have the privilege of going up and embracing the Emperor.” The people attending the ceremony excitedly exercised this privilege, keeping the Emperor kissing and embracing for a full hour.

On the afternoon of Easter Sunday, St. Isaac’s Square became home to “Rope-dancers, Chinese-Shadows, puppet-shows, mechanical and optical representations, strange animals, and the like delights of the Populace.” The square, John Quincy related, was also filled with twenty or thirty carnival rides, “filled by a succession of men, women and children who keep them in perpetual motion.” He observed that the fair was enjoyed only by “the lowest classes,” and that anyone who owned or could hire a carriage spent the afternoon circling the Square, “beholding all these amusements. . .and at the same time exhibiting themselves, and their Carriages, and Liveries and Horses, in Spectacle to one Another.”

One tradition that pervaded all classes was the custom of giving eggs, which was “as universal as that of kissing,” John Quincy told his mother. Those in the lower classes exchanged hard-boiled eggs that were dyed red. People with greater wealth gifted artificial eggs made of everything from marble and porcelain to candied sugar. John Quincy assured Abigail that his four-year-old son was partaking in the festivities. “Boxes of Sugar-plums assume this form in presents for children, much to the entertainment of master Charles.” Charles also had the opportunity to gaze in shop windows lavishly decorated with “multitudes of these artificial eggs, of various sizes, suspended by silk ribbons of all the gaudy Colours” and to hear street vendors hawk the candy eggs, gingerbread, and other candy. “In short,” John Quincy concluded, “these objects are so multiplied at these times before the eyes of a Stranger to the Custom, that he would almost be induced to believe that in Russia, breeding eggs, and kissing was the business of human life.”