By Susan Martin, Collection Services

This is the fourth post in a series about the wartime experience of Charles Cornish Pearson. Go back and read Part I, Part II, and Part III for the full story.

After a short hiatus, I’m happy to return to the story of Sgt. Charles Cornish Pearson of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion in World War I. We last heard from him in April 1918, so I’ll pick up now in May. I’ve been looking forward to this installment because it was during this month that Charles wrote some of my favorite letters in the collection.

Things were relatively quiet for Charles’ battalion after the terrible Battle of Seicheprey in northeastern France. Philip S. Wainwright says very little about the month of May 1918 in his History of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, except that it “passed uneventfully.” But I imagine these calmer periods gave soldiers time to pause and reflect on their experiences, for better or worse. Certainly Charles wrote longer and more introspective letters this month, and in them he took a broader look at the war he’d been fighting for almost a year. He was housed in barracks somewhere near Seicheprey when he wrote to his parents on the 5th.

Please get the idea of the awfulness of this war out of your head […] We are not such a terribly afraid lot and as long as they keep us supplied with the necessary articles of food clothing & ammunition why we don’t kick a great deal. Money supplies & less politics are what we need over here and I hope the people in the U.S. will gradually awaken to these facts & the sooner they do so why the sooner the war will be over.

As for his recent “exciting experiences,” Charles showed remarkable composure (or at least put on a brave face for his family). His letters give us a fascinating look into the psychology of soldiers in the trenches.

Now that we have done our bit at the Front & had a taste of gas, shells air raids etc. why there isn’t much new to experience & one settles down to take it all as it comes. Do our bit & then try to forget about it as quickly as possible. […] We aren’t down hearted, but don’t think that we forget the serious side of this business and realize that the next day may be the time that we get our stomachful a plenty. Its all a matter of chance anyway & […] it makes little difference what you do, if its your turn, why you get it.

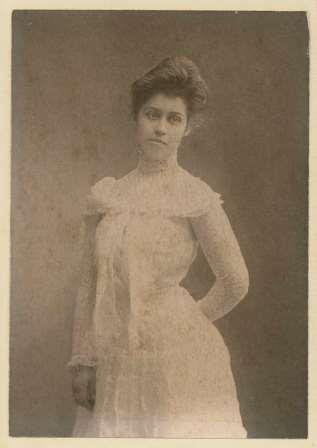

Fifteen days later, still enjoying the well-deserved rest and relaxation, he wrote at length to his younger sister Jean. The collection came with one photograph of her, taken ca. 1910-1915.

Jean—short for Jeannette—was about 26 years old in 1918 and lived in Masters, Colorado, with her husband Thomas B. McPherson and, I think, a young son and daughter. Unfortunately, the MHS doesn’t hold her letters to Charles, but she’d been a steadfast correspondent, often sending cigarettes and care packages. His letter, dated 20 May, reveals not only his affection for her, but also his sense of humor, compassion, and humility. After reassuring Jean that things were fairly quiet (“You don’t care for excitement these days after you have had a little of it”), he launched into a description of another soldier named Charlie. I particularly like his euphemism “over the weather,” which was a new one for me.

[He] was a little Sicilian in my old squad who when ever he got tight found the English language a little beyond him. […] He sure was a comical chap and furnished us with many a laugh. Used to always call me “Boss” and when he came in evenings a little bit over the weather would have to sit on the edge of my bunk and tell me all his troubles. Poor Charlie, he was not a success at the front. He developed a case of shell shock and was sent back to the Base and suppose we will never see him again.

Later he corrected a misunderstanding in his endearingly modest way.

Where do you get that “Hero” stuff in your last letter? Indifference to fear etc. Don’t you believe it for a minute. Yours truly is just as frightened as the next fellow and can duck and run for dug-out just as quick as the next fellow. Still this fear stuff doesn’t figure a great deal at that; you may be scared to death still if you have to do something why you have to, that is all.

And he explained in no uncertain terms who the real heroes were, downplaying his own hardships and betraying not even a trace of self-pity.

Besides as far as danger goes we don’t get it the way the doughboys do, he is the fellow that stands the brunt of this war and deserves the credit even more than any other line of service, aviators not excepted. Why? because he stands real hardship which many of us are lucky to get out of. He goes up to the trenches for six or seven days at a stretch, lives in mud and water, gets very little sleep and eats when he gets a chance […] To see those boys hiking back from the trenches makes one (who doesn’t get that part of the game) think that doughboy is the fellow to be pitied.

Stay tuned for Part V of Charles’ story.