By Erin Weinman, Reader Services

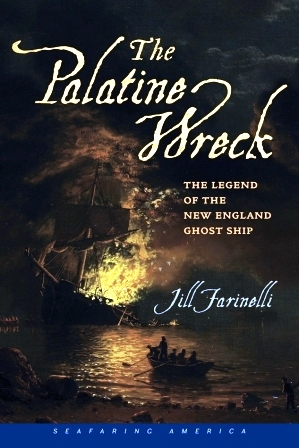

For nearly three centuries, stories of a burning ghost ship haunted the residents of Block Island, Rhode Island. Although it is unknown what it was witnesses have seen, the origin of “The Palatine Light” tells a different tale then the one passed down through popular culture. The Palatine Wreck: The Legend of the New England Ghost Ship by Jill Farinelli examines how the legend developed from the wreck of the Princess Augusta and explores how legends can emerge from public memory. By examining surviving letters of passengers, notarial records, and newspaper accounts of merchant ships, Farinelli was able to piece together a narrative of the Princess Augusta’s final journey in 1738 (xv-xvii). Further information on witnessed accounts of the ghost ship and surviving artifacts of the shipwreck was provided by Block Island’s historians. Jill Farinelli has worked as a freelance writer and editor for twenty-five years in Boston, Massachusetts. The Palatine Wreck is her first work of historical non-fiction.

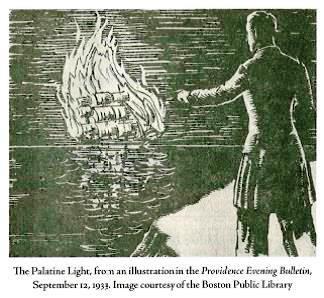

In January 1867, the poet John Greenleaf Whittier published a poem titled “The Palatine” in the Atlantic Monthly. Based on a tale he heard from a friend, the poem was the first to launch the legend of “The Palatine Light” into mainstream society (158).

“The Palatine Light, from an illustration in the Providence Evening Bulletin, September 12, 1933. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.”

For still, on many a moonless night,

From Kingston Head and from Montauk light

The spectre kindles and burns in sight.

Now low and dim, now clear and higher,

Leaps up the terrible Ghost of Fire,

Then, slowly sinking, the flames expire.

And the wise Sound skippers, though skies be fine,

Reef their sails when they see the sign

Of the blazing wreck of the Palatine!

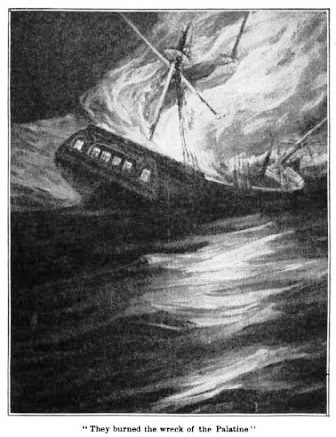

“They burned the wreck of the Palatine.”

The origin of the Palatine Light legend began in 1738. Palatines, a name given to the people who resided in regions along the Rhine of modern-day Germany, began emigrating in vast numbers in the early 18th-century. As Farinelli examines, over 6,500 emigrants made their way to the British colonies in 1738 alone in hopes of a better economic opportunity in the Pennsylvania colony (169). Unfortunately, the 1738 sailing season would be one of the deadliest in history, with a death rate of 35 percent. Massive storms in the Atlantic and ill-preparation for numerous overcrowded ships were to blame. The Princess Augusta departed from Rotterdam in June 1738 with an estimated 340 passengers. While only 68 would survive the journey across the Atlantic, it was the ship’s destruction within the sandbanks of Block Island that brought wide-spread attention to the voyage.

Farinelli explores how such a common story captivated the public’s mind in final section of the book. Why was the Princess Augusta the event to be immortalized? One idea Farinelli explores is the rise of the Spiritualist Movement in the 19th century. People became interested in the paranormal and were simply captivated by stories believed to be started by the ship’s survivors, allowing them to remain popular amongst New Englanders (144-145). While Farinelli and other researchers are unsure what exactly caused the illusion of a burning ship, the legend has been embraced by many New Englanders.

“Map of Block Island.

Map: Patti Isaacs, 45th Parallel Maps and Infographics.”

Farinelli’s research on the works of 19th-century New England writers, interviews with local Block Island historians, and years of researching Palatine emigration allows The Palatine Wreck to work as a case study for how history can transform itself into legend. A mixture of human tragedy fueled by the national rise in Spiritualism sparked interest amongst artists, who used the legend within their own fictional works. Whittier may have been the most famous example, but a number of writers had interpreted the event in their own ways. The emergence of Spiritualism sparked interest in these types of tales, combined with increased tourism in Block Island. At the end, Farinelli points out that this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

In the end it doesn’t matter whether the Palatine Light is a phantom, a figment, or a floating mass of dinoflagellates. Because the light has become an integral part of the legend, its reappearances has served a continual reminder of the tale. Without it, the Princess Augusta and its many passengers lost to the sea, would be lost to history as well. (152).

This book may be of particular interest to those who study transatlantic migration, German migration, and the development of public memory. Local New England residents who are familiar with the tale of “The Palatine Light” may also be interested, as the book provides a thorough background to the incident. The Massachusetts Historical Society holds a number of collections that complement the themes of this book including Palatine migration, transatlantic history, spiritualism, and maritime culture:

Manuscripts

Depositions of officers of the Palatine ship Princess Augusta, 1939

The Palatine, or, German immigration to New York and Pennsylvania, 1897

John Erving logbooks, 1727-1730

Log of the Brigantine Dolphin, 1732-1734

Printed Material

Early eighteenth century Palatine emigration: a British Government Redempitioner Project to Manufacture Naval Stores by Walter Allen Knittle [Philadelphia: S.N., 1936]

Boston in the Golden Age of Spiritualism: Séances, Mediums, and Immortality by Dee Morris [Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014]

To work with these materials, or any other collections at the MHS, consider Visiting the Library!

*****

[Updated, 5 March 2018, to include images.]