By Susan Martin, Collections Services

Your reference to the southerners regard, or rather, disregard of the Negro [–] I experienced a rather amusing incident a few weeks ago.

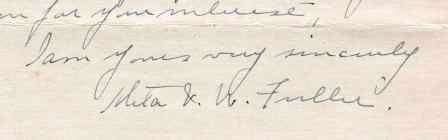

This passage comes from a letter written by African-American artist Meta Warrick Fuller on 5 January 1928 and recently acquired by the MHS. Fuller’s correspondent was Marion Colvin Deane, a white Canadian woman who worked at Virginia’s historically black Hampton Institute. Deane was an avid collector of autographs, particularly those of famous black writers, artists, educators, intellectuals, and activists. She wrote to Fuller, W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Walter F. White, and many others soliciting autographs for her collection.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968) was an accomplished and acclaimed black sculptor associated with the Harlem Renaissance, though her work spanned the decades both before and after that era. Born in Philadelphia, her early artistic promise was nurtured by her family, and she studied art in Philadelphia before traveling to France in 1899 to attend the Académie Colarossi and the École des Beaux-Arts. In France, she met and was mentored by Auguste Rodin. Her work was exhibited alongside older and more established contemporaries like John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt, and she would go to win many commissions and awards over her lifetime.

In 1928, when Marion C. Deane wrote to her, Fuller was living in Framingham, Mass. with her husband Solomon Carter Fuller and their three sons. She worked in her own private studio behind the house.

Fuller began her reply to Deane by apologizing for her handwriting and thanking Deane for “the kind interest and regard – may I be worthy of them.” Then, in response to a comment by Deane on Southern racial animosity, she described a recent “amusing incident” on a Framingham bus. Returning from a shopping trip and finding the bus crowded, Fuller opted to sit in the back, although for her this was “contrary to custom.” From there, she overheard “a youngish sort of woman”—a white woman presumably visiting from the South—talking to a friend.

I could still hear the conversation – she spoke of how strange it seemed to see colored people mingling with white people – in schools – restaurants and the like – she would go out if one sat down at a table with her – it didn’t seem right.

And what was Fuller’s reaction? Maybe not what you’d expect.

It all impressed me as very funny – and mischief got the better of me – I wrote on a slip of paper ‘God made man of one flesh[.]’ I rolled it up, and as I passed on my way out dropped it in her lap. I was convulsed at the expression of surprise when she saw what I had done, but I left the car before she had time to read it. I have not since seen the woman with whom she was talking but I am curious to know what she did after reading it.

The MHS currently holds no other papers of Meta Warrick Fuller, so this letter is a very welcome addition to our collection. It’s also a fascinating record of racial attitudes in the years between the Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” decision and the height of the civil rights movement in America.