By Shelby Wolfe, Reader Services

During a recent search in our online catalog, ABIGAIL, I came across two subject headings that caught my attention – “Single women” and “Boardinghouses—Massachusetts.” These struck me as familiar since during my first years in Boston as a single graduate student I lived in something similar to a boarding house just a few minutes’ walk from the MHS. Six floors of 160-square-foot rooms housed over one hundred single women, mainly students and young professionals, with the occasional resident who had lived there for decades. In my circle of friends, the building is commonly referred to as “the convent” – after all, that’s what it once was and retains traces of with its still-used chapel and a scattering of Catholic iconography, figurines, and crucifixes throughout.

Like you might expect, living in the convent came with its fair share of rules – no visitors allowed beyond the first floor common areas, shared kitchens close at 10:00 PM, shared bathrooms must be kept tidy, no food allowed in certain areas, no alcohol, no candles, quiet hours must be respected, etc. Even with its rules, living in the convent was a privilege – central location, affordable rent, and—perhaps my favorite part of all—a community of fellow residents from a variety of backgrounds who held a range of unique interests and skills.

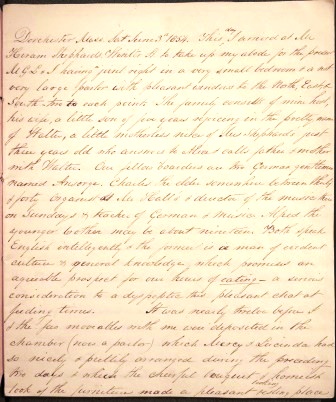

I was fascinated to read in Elizabeth Dorr’s 1845-55 and 1859 diaries (where the aforementioned subject headings of “Single women” and “Boardinghouses” led me) about the diarist’s day-to-day activities and interactions while living in a 19th-century boarding house. Elizabeth Dorr, who worked as a tutor and never married, first describes her Dorchester lodgings and fellow boarders in a diary entry on Saturday, 3 June 1854:

This day I arrived at Mr. Hiram Shephards, Winter St. to take up my abode for the present. MGL and I having a joint right in a very small bedroom and a not very large parlor with pleasant windows to the North, East, & South – two to each point. The family consists of mine host, his wife, a little son of five years rejoicing in the pretty name of Walter, a little motherless niece of Mrs. Shephard’s just three years old who answers to Alice and calls father & mother with Walter. Our fellow boarders are two German gentlemen named Ansorge. Charles the elder somewhere between thirty and forty. Organist at Mr. Hall’s and director of the music there on Sundays & teacher of German & Music. Alfred the younger brother may be about nineteen. Both speak English intelligently & the former is a man of evident culture & general knowledge which promises an agreeable prospect for our hours of eating – a serious consideration to a dyspeptic this pleasant chat at feeding times.

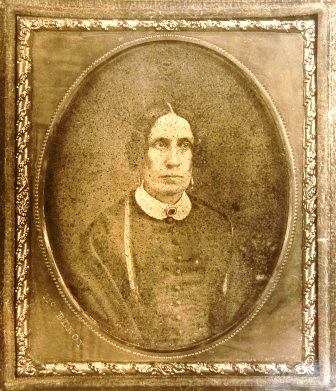

Elizabeth Dorr, [photograph] [19–]

Copy photograph of a daguerreotype of Elizabeth Dorr. Taken by an unidentified photographer.

While she doesn’t indicate any rules or conditions of occupying her rooms (of course, she wasn’t living in a convent), Elizabeth fills the pages with delicately transcribed accounts of social visits from friends, invitations to tea, and remarks on the weather. Some days are filled with three or four social visits (she could have friends over!) and outings to the Academy or a stop at Thornton’s for soda. Other entries reflect a different pace: Monday, 7 November 1859, “Too entirely exhausted to go to tea at Mrs. Rodman’s”; Sunday, 13 November 1859, “Dull. at home all day.” I learned from her 1854 diary that Friday, 21 July 1854, was “Too warm for action” and the Friday after Thanksgiving in 1859 was “almost summerish.”

The final page stood out from the rest as I read Elizabeth Dorr’s 1859 diary – the latest in the collection. She begins with one of those lines in a diary that transports a reader out of an individual’s personal life and solidly reminds one of the greater context in which this person lived – Friday, 2 December 1859, “Returned by Belleview road, bells ringing at the African church as we returned on account of John Brown’s execution.” The final lines of the diary, written two days later, absorb the reader back into Elizabeth’s daily routine of omnibus excursions and social visits, ending aptly with plans “to see a friend.”

If you are interested in viewing Elizabeth Dorr’s diaries yourself, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for assistance.