By Sara Georgini, Adams Papers

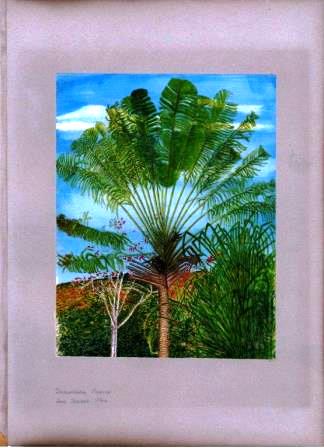

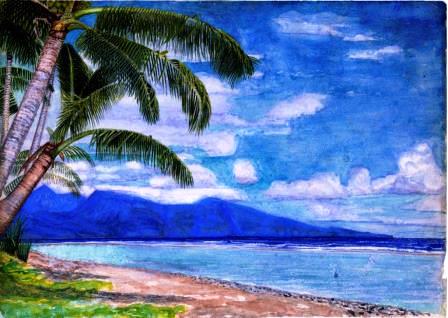

At eight o-clock on a January morning in 1891, and a world away from the ice-caked streets of his native New England, 52-year-old Henry Adams leisurely began to go about his day. Armed with coffee, he surveyed the two-room cottage that he had rented in Apia, Samoa, with the artist John LaFarge. Eager to skip the worst heat of the day, he puttered inside, answering letters and reading Homer. Often, Henry unearthed his 24-tube watercolor set and “whacked great daubs of color on paper,” creating a lush portfolio of postcard views of the local paradise. Just before dusk, Henry paddled out in a small, rough-hewn canoe. On some evenings he kept to the harbor and stared down the Pacific Ocean’s crashing walls of surf. Other nights, Henry rowed right on past, idling in the refuge of Matafangatele’s deep bay. A cozy dinner on the veranda, with strong cigars and a full stack of new novels, followed next. Local residents, laughing and chatting their way down the grass path, hailed the American historian lounging between the coconut palms: “Alofa, Akamu!” (“How are you, Adams”). “Such a life,” Henry Adams wrote home, “seems pleasant enough, especially in Beacon Street in winter, but a true traveller should be restless, and I am qualified in that particular to be high in the profession.”

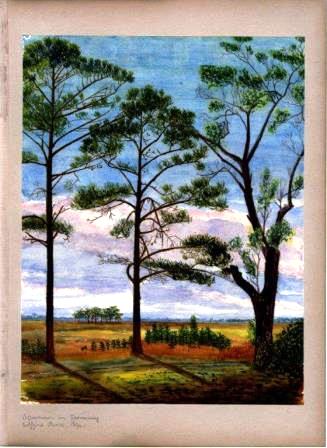

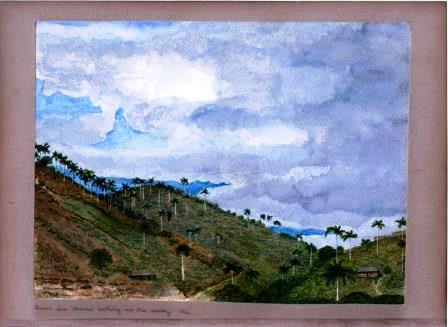

Henry Adams (1838-1918), Harvard professor of medieval history and eponymous author of the provocative Education, spent most of his life on the road. Adams traveled widely, soaking up foreign experiences and reveling in aesthetic journeys through Europe, Latin America, Japan, and the South Seas. Throughout the 1890s, he saved his warm-weather destinations for Boston’s bitterest months. He steamed off to Samoa, Cuba, Mexico, and Tahiti with friends, books, lavish wardrobes, and prized watercolors in tow. Partly inspired by his late wife Clover’s photography, Adams spent the last decades of his life capturing the sights and scenes of the late Victorian world as he traveled through it. Like many Americans, Henry adopted the post-Civil War passion for watercolors as a way to document natural beauty. In letters sent from exotic datelines like Coffin’s Point, Dos Bocas, and Apia, Henry reveled in his amateur pursuit. “I slobber water-colors again,” he told John Hay. “I labor whole days to do the most prosaic field I can find, and at the end of the week I throw it away in despair,” he confessed to Elizabeth Cameron. Later that year, camped in “Yellowstone country,” Adams plied his brushes to make the views on display in our Yankees in the West exhibit, but thought his niece Mabel Hooper would have done a better job. “I wanted you there to sketch for me. I was quite sick in spirit that I could not catch a tone of the country, for it was American to the very snow,” he wrote to her on 6 October 1891. “I wanted awfully to be an artist to see if I could make anything out of the American ideal, which is like the American women–not suited to pictorial or plastic art.” (Learn about Mabel Hooper LaFarge’s art career–including her watercolor portrait of Henry–here, thanks to Houghton Library).

Henry, who honed his critical edge at the North American Review’s helm, was hard on his own artistic abilities. “I have passed my morning trying to finish a sketch, but my sketches here are more lamentable than ever, and break my heart with mortification,” he wrote of Mexico. “Ten thousand objects about us are crying out to be painted, but the simplest are too difficult for me, and the difficult ones are a chaos of lights and lines… If I could only do some of the ravines in the hills, with sides of rock, and with sunlight dropping down through a network of foliage, and lianas, on ferns and mosses, I could amuse myself forever, but one such sketch would need a year, if it attempted drawing. The greens here are the richest I ever saw, and as for the reds, the earth and sky glow with them.” Journey here for information on Henry Adams’ watercolors.