By Susan Martin, Collection Services

After you’ve processed several collections of papers here at the Massachusetts Historical Society, you start to see familiar names crop up. It’s not just the usual Cabots and Saltonstalls and Lowells, etc., or those famous Boston ministers, merchants, and abolitionists. There’s also Edward Atkinson, who seemed to know just about everybody. I find that reformer Dorothea Dix makes a fairly regular appearance. But there’s one correspondent I’ve come across a few times that intrigued me, not least because of her beautiful handwriting. She was known by various names: Esther Frances Alexander, Francesca Alexander, or just plain Fanny Alexander.

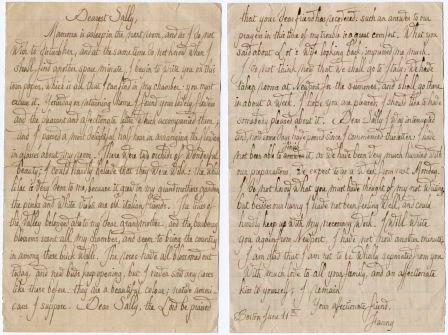

Fanny was an illustrator, author, folklorist, and translator. Her father was portrait painter Francis Alexander, and her mother Lucia (née Swett) was an etcher, author, and philanthropist. Fanny was their only child, born in Boston on 27 February 1837, although she spent most of her life in Italy. Fortunately for us, she kept up a correspondence with friends around the world. Her letters appear in a few different collections at the MHS, including the Bowditch-Codman-Balch and Fay-Mixter family papers. Her most substantial and personal letters here are the five she wrote to her friend Sally Hayward in the Joseph H. Hayward family papers.

Fanny wrote to Sally in great detail about her life in Italy and her artistic work. The letters typically run to at least four densely written pages and cover a variety of subjects. For example, on 28 February 1871, Fanny condoled with Sally on the death of her cousin, congratulated her on the imminent birth of a nephew, and recounted a story she’d read that inspired her latest sketch.

The story comforted me so much, that I could not resist turning it into a picture in pen and ink, which will be the first of my works ever offered for sale in Boston. […] I should like very much to have you see it, as it is a picture which I have put my whole heart into, as I have hardly ever done into any picture in my life.

She also described her painting studio “up under the roof.”

It is a pretty little room, and always full of flowers, so that it looks like a garden. […] I have a few little presents there, almost all from poor people; those which I receive from the rich are disposed of in the room down stairs, but my little painting room is the poor people’s room especially.

A few months later, Fanny wrote about another project she’d begun.

I am busy, among other things, in writing down a curious collection of legends and poetry, which I learnt long ago at Abetone, and which it seems a pity should be forgotten. I think that I shall have it printed some time, but how or where, I have not the least idea.

In 1882, legendary art critic John Ruskin was introduced to Fanny’s work, and he was impressed by her skill and simplicity. He went on to publish volumes of her art and stories and is usually credited with bringing her to the attention of the wider world. But Fanny would be remembered not only for her creative output, which inspired sonnets by James Russell Lowell and John Greenleaf Whittier, but also for her piety, her love of nature, and especially her charity. Many poor Italians considered her a saint.

She also lived in Florence during a time of great change. This passage from her letter of 12 December 1874 is particularly interesting.

Florence is now sadly changed since I first knew it; modern ideas have arrived even here, with the usual modern antipathy to everything venerable and beautiful; they have taken down our grand old walls, that were nearly six hundred years old, and have, for the sake of widening the business streets, and the bridges, destroyed some chapels, and other buildings, of great antiquity and beauty. All these things have grieved me more than I can tell you. […] However, there is no alternative but to die young, or to see changes.

Fanny lived a very sheltered life, with no formal education. In 1885, her eyesight began to fail, and she was all but blind by the end of her life. She had also broken her hip and walked with a crutch or cane. But on 22 August 1910, in a letter to Charles P. Bowditch, her mother Lucia described Fanny as busy and content.

Her room is full of the poor and the rich, who all make friends, and read the Bible, and eat bread and chocolate in company. Half blind and whole lame, she is the happiest of the happy.

Fanny’s father died in 1880. Fanny and Lucia lived together the rest of their lives, devoted to each other. According to Notable American Women, 1607-1950 (p. 35), “After the death of her mother in 1916 at the age of 102, Francesca took to her bed and remained there until her own death, at seventy-nine, the following January.” She is buried with her parents in Florence.