By Susan Martin, Collection Services

We feel very badly that you were compelled to take part, through your men, in the destruction of Darien, & fully sympathize in the sentiments you express. I sincerely hope that as Genl Hunter has been relieved, there may be a modification of the policy which caused the perpetration of such a deed, & that you may not be obliged again to participate in anything so repugnant to you.

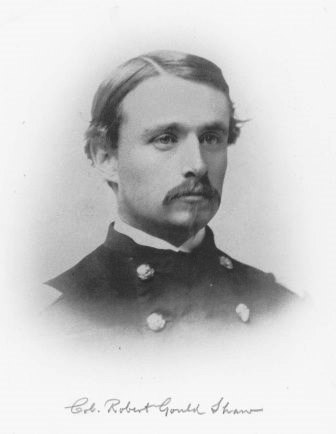

This excerpt comes from a letter written by Francis G. Shaw to his son Robert Gould Shaw on 23 June 1863, part of the Shaw-Minturn family papers at the MHS. Twelve days earlier, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the African-American regiment Robert commanded, had participated with other troops in a raid on the town of Darien in southeast Georgia.

Unfortunately, our collection doesn’t include Robert’s original letter, but Francis was probably replying to the one Robert wrote to his wife Annie the day after the raid, which she sent on to his parents. Robert’s letter to Annie has been printed in Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune (1992) and other publications.

According to his account, when Union troops arrived at Darien, they found the place all but deserted. James Montgomery, colonel of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry (another black regiment) and post commander, had the furniture, livestock, and other movable property confiscated, then smiled “a sweet smile” at Shaw and said, “I shall burn this town.” Shaw explained:

I told him, “I did not want the responsibility of it,” and he was only too happy to take it all on his shoulders; so the pretty little place was burnt to the ground, and not a shed remains standing; Montgomery firing the last buildings with his own hand. One of my companies assisted in it, because he ordered them out, and I had to obey. You must bear in mind, that not a shot had been fired at us from this place, and that there were evidently very few men left in it. All the inhabitants (principally women and children) had fled on our approach, and were no doubt watching the scene from a distance. […]

The reasons he gave me for destroying Darien were, that the Southerners must be made to feel that this was a real war, and that they were to be swept away by the hand of God, like the Jews of old. In theory it may seem all right to some, but when it comes to being made the instrument of the Lord’s vengeance, I myself don’t like it. Then he says, “We are outlawed, and therefore not bound by the rules of regular warfare”; but that makes it none the less revolting to wreak our vengeance on the innocent and defenceless.

Shaw called it a “dirty piece of business” and “as abominable a job as I ever had a share in.” He hated “to degenerate into a plunderer and robber. […] There was not a deed performed, from beginning to end, which required any pluck or courage.” He also feared the raid would damage the reputation of black soldiers. Montgomery’s actions were “barbarous” and gratuitous, he thought, and made him no better than notorious Confederate raider Raphael Semmes. But disobeying orders would have meant a court-martial. Shaw lamented, “after going through the hard campaigning and hard fighting in Virginia, this makes me very much ashamed of myself.”

Luis F. Emilio, another officer of the 54th, wrote about the Darien raid 28 years later in his history of the regiment. Emilio also described the beauty of the town, as well as the looting and destruction carried out by Union troops. But while Shaw’s account was thoughtful and conflicted, Emilio’s was a little more clinical and didn’t address the ethical questions.

Robert Gould Shaw and many other men of the 54th Regiment were killed during the assault on Fort Wagner just a few weeks after the destruction of Darien. Another letter in the Shaw-Minturn collection, written by Rev. Phillips Brooks, summarizes Shaw’s legacy. Brooks wrote to Robert’s mother on 17 Nov. 1892: “Indeed, he belongs to all of us, & to the country, & to history.”