By Brendan Kieran, Reader Services

While the MHS is not home to a large collection of court records, I recently viewed two items we do hold relating to fornication in 18th-century Massachusetts. These materials concern judicial proceedings that were separated by nearly sixty years, but provide interesting glimpses into the criminalization of sex in colonial Massachusetts. Through further investigation, I learned more about the ways the judicial system addressed sexuality during this period, including the significance of race and gender within the system.

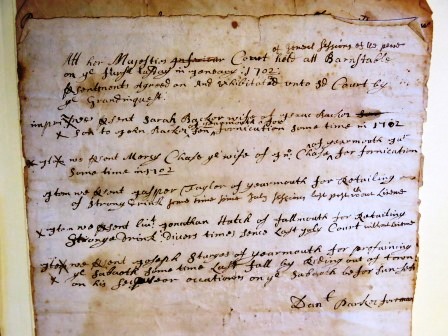

A small collection of Barnstable County (Mass.) legal documents includes one “memorandum of presentments to the Court of General Sessions of the Peace.” This January 1702 document, which bears the signature of foreman Daniel Parker, notes two cases of unlicensed sale of liquor, one case of profaning the Sabbath, and two cases of fornication. The people accused of fornication are Sarah [Backer?] and [Mercy Chase,] both of whom were married at the time; each supposedly engaged in “fornication some time in 1702.”

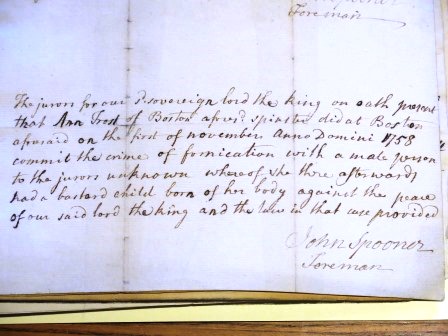

A Grand Jury presentment, 1 January 1760, located in our Miscellaneous Bound Manuscripts collection, notes an accusation against Ann Frost, a Boston resident who supposedly engaged in fornication on 1 November 1758. The man involved was “to the jurors unknown.” Frost had a child out of wedlock, “against the peace of our said lord the king and the laws in that case provided.” This presentment bears the signature of foreman John Spooner and was created for a Court of General Sessions of the Peace for Suffolk County-ordered grand jury.

In Regulating Passion: Sexuality and Patriarchal Rule in Massachusetts, 1700-1830 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), Kelly A. Ryan (a former Andrew W. Mellon fellow at the MHS) writes that, during the 18th century, white women became the main targets of fornication charges in the Massachusetts judicial system, while punishment of men for fornication dwindled beginning in the mid-17th century as sex outside of marriage came to be seen as a legal issue for women, not men (13-14, 21-23). Additionally, for much of the 17th-century colonial period, “premarital sex” was the main cause of fornication charges; however, in the late 1600s and early 1700s, men increasingly ceased to face judicial consequences for premarital sex (22-23). Also beginning in the late 1600s and extending through the 18th century, “nonmarital sex” became more common among fornication charges against women, as “the court and communities were especially concerned with remedying the problem of disorderly white women” (23-24). These charges were used to justify patriarchal control of white women; however, women accused of fornication did find ways to push back, including by resisting attempts of justices of the peace to elicit names of men involved (13-15, 30-32).

Engagement with the justice system for sex crimes did not look the same for men and women of color as it did for white people, though. According to Ryan, African Americans faced fornication charges in the 17th century, but African Americans and Indians experienced increasingly fewer such prosecutions during the 18th century (74-75, 77). This lack of prosecutions served to uphold white patriarchy by preventing white men from facing consequences for sexual contact with women who were enslaved while denying women of color agency and preventing African American men from being able to seek paternal rights (74, 78, 82). White women faced legal consequences for fornication with African American men, along with social disapproval for sex with Indian men; these actions were intended to enforce the notion that white women should be with white men (78-79, 82). Ultimately, according to Ryan, “[g]overnment prosecutions promoted white men’s sexual authority, partnerships between white women and white men, and the removal of paternal and sexual rights for men and women of color” (82).

Feel free to visit the MHS library if you would be interested in viewing materials in our collections. The library is open Monday through Saturday!