By Rhonda Barlow, Adams Papers

When President John Quincy Adams delivered his first annual message to Congress on December 6, 1825, he noted that “the want of a naval school of instruction, corresponding with the Military Academy at West Point, for the formation of scientific and accomplished officers, is felt with daily increasing aggravation.” But Congress was not sufficiently aggravated to establish a school. Because young naval officers could learn to handle a ship only at sea, it seemed reasonable for all their education to be conducted aboard ship.

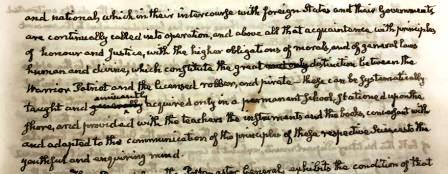

On December 4, 1827, Adams gave his third annual message to Congress, and for the third time, recommended the establishment of a naval academy similar to West Point, which Thomas Jefferson had established twenty-five years earlier. But this time, Adams explained his view of naval education in detail.

Adams held high standards for the “enquiring minds” of “the youths who devote their lives to the service of their country upon the ocean.” In his 1827 message, he explained that the academy he envisioned needed teachers, books, equipment, and a permanent location on shore. Subjects should include not only shipbuilding, math, and astronomy, but also literature, “which can place our officers on a level of polished education with the officers of other maritime nations,” and knowledge of foreign laws. As a former diplomat, and secretary of state from 1817 to 1825, Adams recognized that naval officers were a special class of American ambassadors.

But this combined scientific, technical, and liberal education was not enough. “Above all,” Adams continued, a young naval officer needed to learn “principles of honour and Justice” and “higher obligations of morals.” For John Quincy Adams, an American naval officer was a “Warrior Patriot,” equipped with a moral education that distinguished him from a mere pirate.

An entry in Adams’ Diary, made a few days after his 1827 speech, sheds light on his understanding of the role of morality in officer education. In his Diary, Adams reflected on the court martial of Master Commander William Carter for drunkenness.

Although he was reluctant to end Carter’s naval career, he wrote that “such enormous evils from intemperance demanded a signal example.” While intoxicated, the master commander twice was guilty of giving orders that almost caused the ship to founder, endangering both the valuable warship and her crew. On another occasion, he had been rude to a British officer. On another, he had engaged in disorderly conduct on shore, observed by, among others, a British officer. Adams’ Diary reveals that moral education was about self-control and responsibility, and the reputation of America’s fledgling navy abroad, especially among the British, whose Royal Navy was the envy of the world.

Adams failed to convince Congress to establish a naval academy. But eighteen years later, Adams, then a congressman, met with George Bancroft, the new secretary of the navy. In his Diary, Adams recorded that Bancroft “professes great zeal to make something of his Department.” A few months later, on October 10, 1845, Bancroft opened the Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD.