By Susan Martin, Collections Services

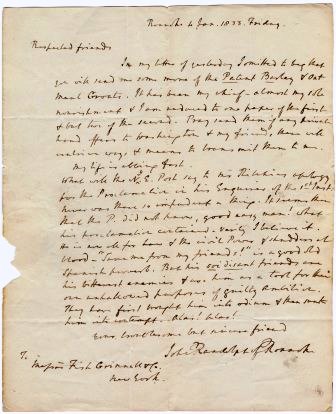

The recently acquired MHS collection of Shaw-Minturn family papers has received its fair share of well-deserved press, particularly related to the discovery of the famous sword carried by Robert Gould Shaw at the assault on Fort Wagner. I hope to write more about the Shaw letters in a later post. But the collection also contains some interesting papers from the Minturn branch of the family, including letters written by John Randolph (1773-1833) during the last year and a half of his life.

“John Randolph of Roanoke” (as he is usually known) was a Congressman, minister to Russia, tobacco planter, fiery orator, vehement anti-Federalist, and all-around difficult man to get along with. The seventeen Randolph letters in this collection were written to Fish, Grinnell & Co. of New York, shipping merchants who procured and shipped items for Randolph that he couldn’t acquire in Virginia. (Fish, Grinnell & Co. became Grinnell, Minturn & Co. when Robert B. Minturn joined the firm. Robert Gould Shaw’s sister married Robert B. Minturn, Jr.)

In October 1831, when the letters start, Randolph was only 58 but suffered from a variety of physical ailments, including the tuberculosis that would ultimately kill him. His first few letters deal primarily with business matters, but on 9 February 1832, he launched into an angry discourse on banking policy and the upcoming presidential election. A New York newspaper had apparently reported that Randolph’s support for Andrew Jackson was wavering.

I am & ever shall be I hope the friend of Genl. Jackson. But deadly opposed as I am to the Bank of the U.S. I cannot support his ministers [Louis] McLane & [Edward] Livingston who are its warm supporters. I will do nothing & say nothing that can injure his re-election […]

Randolph also had a few choice words for Martin Van Buren and John C. Calhoun (and a bad prediction).

Neither of them [will] ever be President of the U.S. & Heaven forbid that either ever should be. Although I think the N. Yorker much less objectionable than him of South Carolina, I should be very sorry to see him in an office for which in my poor judgemt. he is unfit, wanting that weight & dignity of character & manners which are more essential than the greatest abilities & which Genl. Washington alone (in my opinion) of all our Presidents possessed.

One of the issues that got Randolph fired up was the Second Bank of the United States. Jacksonian Democrats believed that a central bank violated state sovereignty and the Constitution. Randolph called it “that knot of brokers in Philada. that levy contributions all around them & leave nothing undone to injure the Trade of New York.” But he had confidence in President Jackson. When Congress voted to reauthorize the bank, Randolph reassured Fish & Grinnell that “no Bill re-chartering the present Bank will ever receive Genl. J.’s signature. I have it under his own hand.” And he was right—Jackson vetoed the bill on 10 July 1832.

However, just four days later, Jackson set in motion the Nullification Crisis by signing the Tariff of 1832. This protectionist tariff and its previous incarnation, the 1828 “Tariff of Abominations,” hit Southern states hard. A fed-up South Carolina adopted the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both tariffs void in the state and threatened secession if the federal government used force to compel compliance. Congress called their bluff and passed a bill authorizing the use of military force in South Carolina.

Randolph did not support nullification, but he was disappointed with Jackson and sympathetic to South Carolina. “And yet I fear,” he wrote, “that the people about the President, taking advantage of his own ferocious passions, and thirst for blood, will precipitate us into a conflict, that must end in ruin, no matter which party gets the upper hand.”

Fortunately South Carolina and the federal government would settle on a compromise tariff that defused the conflict, but Randolph’s feelings about the general political situation, combined with his poor health, made him despondent. He wrote on 31 January 1833:

The springs of life are worn out. Indeed in the abject state of the public mind, there is nothing worth living for. It is a merciful dispensation of providence, that Death can release the captive from the clutches of the Tyrant. […] I could not have believed that the people would so soon have shown themselves unfit for free government. I leave to General Jackson, & the Hartford men, and the ultra federalists and tories and the office-holders & office-seekers their triumph over the liberties of the Country. They will stand damned to everlasting fame.

Despite his cynicism, Randolph was a very witty correspondent. I like this passage from his 19 July 1832 letter, when he was considering a move to England and ordered a number of supplies.

After my last, you may well be surprised at the list of articles subjoined, but I have got into the habit of considering myself in a fourfold state – 1. as a dead man, 2. as a living one, 3. as a resident at Roanoke, 4. as residing on the south coast of England […] & I try to provide for each contingency.

We hope you’ll visit the MHS to take a look at the Shaw-Minturn family papers, the Robert Gould Shaw sword, or any of our other terrific resources.