By Neal Millikan, Adams Papers Editorial Project

On February 22, 1821, John Quincy Adams noted in his diary that “two of the most memorable transactions of my life” occurred that day: the ratification of the Transcontinental Treaty between the United States and Spain, and the submission of his report on weights and measures. While the treaty is remembered for orchestrating the U.S. acquisition of Florida, Adams’s work on weights and measures, which he referred to as “a fearful and oppressive task,” is largely forgotten today.

John Quincy’s obsession with the subject began in 1810 when he was minister plenipotentiary to Russia and spent his free time researching the variations among countries’ standard weights and measures. His wife, Louisa Catherine, recorded in her diary on July 21 that he “too often passed” the days “alone studying…no article however minute escaped his observation and to this object he devoted all his time.”

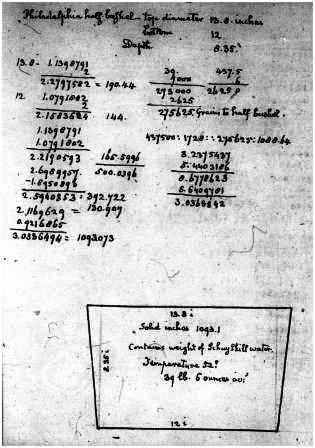

A page of John Quincy’s notes

[John Quincy Adams memorandum and garden book, 1810-1845, Adams Family Papers, microfilm edition, 608 reels (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society) reel 203.]

As secretary of state (1817–1825) John Quincy had many duties, but none intrigued him more than this topic. In 1817, the Senate passed a resolution asking that office to submit “a statement relative to the standard weights and measures” within the states and foreign countries, along with “propositions…as may be proper to be adopted” in America. John Quincy assumed the position on September 22, and by October 7 he drolly noted in his diary that the subject “weighs much upon my mind.” During the summer of 1820 he would wake up early to perform tests and record his results before going to work. Adams’s final report recommended that “no innovation upon the existing weights and measures should be attempted.” He instead called for America to “declare” its official measures “as they now exist” and to give standard metal measurements to “every State and Territory.”

For all his efforts, Adams’s work was not widely read. Indeed, his own father, John Adams, referred to it on May 10, 1821, as “a Mass of historical, philosophical chemical mathematical and political knowledge” but noted, “I cannot Say and perhaps Shall never be able to Say I have read it.” Upon the completion of the work Louisa Catherine recorded in her diary: “Thank God we hear no more of Weights and Measures” [January 6], and John Quincy commented on the final report in his diary:

It is, after all the time and pains that I have bestowed upon it a hurried and imperfect work; but I have no reason to expect that I shall ever be able to accomplish any literary labour more important to the best ends of human exertion, public utility, or upon which the remembrance of my children, may dwell with more satisfaction.