By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

For as long as teenagers have had bedrooms, they’ve been pinning their role models up on the wall—a favorite singer, a beloved actor, the best ball player. When John Quincy Adams was fifteen, his bedroom at The Hague held a gilded framed picture of General George Washington. Like many of his contemporaries, John Quincy had the deepest respect for the “truly great and illustrious” Washington, a respect that endured throughout his life.

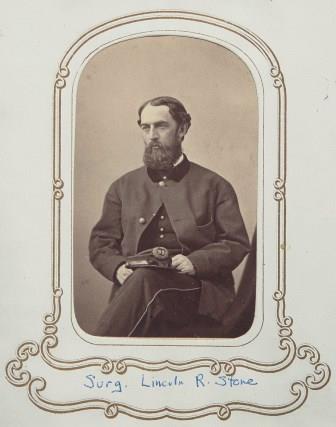

John Quincy’s portrait was likely a copy of John Trumbull’s 1780 portrait of Washington.

[Accessed on 29 August 2017 at: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/24.109.88/]

Twelve years after the portrait of Washington was removed from the wall, John Quincy Adams discovered he would be returning to The Hague thanks to the general’s orders. On May 27, 1794, John Adams wrote to his wife that, “the President has it in contemplation to Send your son to Holland.” When he wrote to his son, he discussed the appointment at The Hague in vague terms, calling the nomination “the Result of the Presidents own Observations and Reflections.” The next day, John Adams penned, “The Senate have this Day unanimously advised and consent to the Appointment of John Quincy Adams to the Hague.”

Just at the beginning of his law career in Boston, John Quincy felt too young and inexperienced to deserve the honor. Nevertheless, he did not believe his father would have suggested it to the president. When he next met his father in Quincy, John Adams confirmed his hunch. “I found that my nomination had been as unexpected to him as to myself,” JQA recorded in his diary. “His satisfaction at the appointment is much greater than mine,” he confessed, writing, “I wish I could have been consulted before it was irrevocably made. I rather wish it had not been made at all.”

Despite his hesitation at being separated from his family and sent halfway across the world for a then-undisclosed purpose, the day before his 28th birthday, JQA was in Philadelphia being introduced to President Washington. “He said little or nothing to me upon the subject of the business on which I am to be sent,” JQA noted. That night JQA was invited to dine with the president, and he paid his respects to Martha Washington, delivering her a letter from his mother. Abigail wanted to acknowledge “the honor done him by the unsolicited appointment conferd upon him by the President.” She continued, “I hope from his Prudence honour integrity & fidelity that he will never discredit the Character so honorably conferd upon him. painfull as the circumstance of a Seperation from him will be to me Madam I derive a satisfaction from the hope of his becomeing eminently usefull to his Country whether destined to publick, or to Private Life.”

A week after receiving Abigail’s letter from John Quincy’s hand, Martha responded. “The prudence, good sence and high estamation in which he stands, leaves you nothing to apprehend on his account from the want of these traits in his character;—whilst abilities, exerted in the road in which he is now placed, affords him the fairest prospect rendering eminent services to his country; and of being, in time, among the fore most in her councils.— This I know is the opinion of my Husband, from whom I have imbided the idea.”

Washington may have felt confident in John Quincy’s diplomatic abilities, but the young man was less sure. As he waited for Alexander Hamilton to return to Philadelphia to deliver instructions relevant to his mission, JQA wrote to his father, expressing doubt about his unfolding career: “I have abandoned the profession upon which I have hitherto depended, for a future subsistence . . . At this critical moment, when all the materials for a valuable reputation at the bar were collected, and had just began to operate favourably for me, I have stopped short in my career; forsaken the path which would have led me to independence and security in private life; and stepped into a totally different direction.” John Quincy ended his letter by telling his father that he determined to return home and to private life in no more than three years, if Washington had not already recalled him by then. John Adams replied urging patience and flexibility. “As every Thing is uncertain and Scænes are constantly changing I would not advise you to fix any unalterable Resolutions except in favour of Virtue and integrity and an unchangeable Love to your Country.”

In 1796 John Quincy learned that his father had been elected to succeed Washington. He wrote to his mother, assuring her that he would never solicit an office from his father. He discussed the devotion he felt to his country and his plans for a private life back in Massachusetts. John Adams was so touched by the letter that he shared it with Washington. Washington communicated his reflections on the private letter to John Adams: “if my wishes would be of any avail, they shd go to you in a strong hope, that you will not withhold merited promotion from Mr Jno. Adams because he is your son.” Washington declared it his “decided opinion” that John Quincy was “the most valuable public character we have abroad,” a man who would “prove himself to be the ablest, of all our diplomatic Corps.”

When George Washington died on December 14, 1799, John Quincy received many letters offering condolences from his family, closest friends, and foreign dignitaries. Poignantly, his father, though overworked in the office of president, sent him a short note on February 28, 1800, acknowledging that John Quincy was mourning the loss of his “great Patron.” Just over a year later, John Quincy welcomed his first son, George Washington Adams.