By Alex Bush, Reader Services

While searching through the MHS’ library catalog, ABIGAIL, for records relating to Mr. Sidney Homer, an 1860s inventor, I stumbled upon a trove of graphics created by Winslow Homer. As a fan of Homer, I admonished myself for not being aware that we had any of his artworks here at the MHS. I did not, however, find any of Homer’s famous paintings in our stacks. Instead, I found evidence of an oft-overlooked part of Homer’s artistic career.

Known for his dramatic depictions of the ocean and idyllic images of country life, Homer’s career as a painter began to take off after his late-twenties. However, he showed artistic talent much earlier in his life in the form of sketches, prints, and other black-and-white media. This includes the MHS’ holdings, a selection of some of Homer’s lesser known work from this earlier period of his life, consisting in-part of prints he created for Harper’s Weekly as an artist-reporter during the Civil War.

Following an arduous apprenticeship at the Boston lithographer J.H. Bufford, 21 year-old Winslow Homer was eager to begin his career as an artist free from the shackles of any sort of contracted work. He became a freelance illustrator, submitting pieces to magazines such as Harper’s or Ballou’s Pictorial. When he was offered a contract as a staff artist for Harper’s in 1860, he turned it down. “The slavery at Bufford’s was too fresh in my recollection to let me care to bind myself again,” he later stated. “From the time I took my nose off that lithographic stone, I have had no master; and never shall have any.” However, after completing a commission from Harper’s to cover the presidential inauguration of Abraham Lincoln at the dawn of the Civil War, Homer began a stint with Harper’s that would end up becoming a formative part of his early career as an artist.

“Presidents Buchanan and Lincoln entering the senate chamber before the inauguration. – (From a sketch by our Special Artist.)” Harper’s Weekly, March 16, 1861, p. 165

With photography still in its developmental period, some of the public’s best sources for images of current events were publications such as Harper’s Weekly. Based in New York City, Harper’s was a political magazine featuring news, stories, illustrations, and more. It was especially active during the Civil War, during which it had nearly 200,000 subscribers, and it worked to provide the public with images, news, and accounts from the front. Part of this endeavor included the hiring of around 30 artist-reporters, tasked with shadowing troops to the warfront and attempting to depict what they saw there. In a short but vivid description from their June 3, 1865 issue, Harper’s explained the project as follows:

They have made the weary marches and dangerous voyages. They have shared the soldiers’ fare; they have ridden and waded, climbed and floundered… The pictorial history of the war which they have written with their pencils in the field, upon their knees, upon a knapsack, upon a bulwark, upon a drum-head, upon a block, upon a canteen, upon a wet deck, in the grey dawn, in the dusk twilight, with freezing or fevered fingers…–this is a history quivering with life, faithful, terrible, romantic.

Winslow Homer was one such artist, although he was not assigned to a particular unit as were most of his colleagues. He made several trips to the front over the course of the war, but completed most of the actual depictions of what he saw there back at his studio in New York. His first trip to the front was likely around October of 1861, during which he focused on the Army of the Potomac. He did not witness any fighting as the army had recently returned from its defeat at Bull Run and was undergoing reorganization. The majority of Homer’s depictions of the war featured army life rather than actual fighting—soldiers setting up camp, eating, receiving medical care, or generally palling around. His images of camp are jovial and often humorous, highlighting the solders’ camaraderie and rowdiness. When compared with other artists’ depictions of soldiers from that time, Homer’s soldiers are distinctive in their quality of expressivity in contrast to other square-jawed, conventionally patriotic representations of “heroic” troops. Though Homer did have a few pieces of a more patriotic nature, such as “Songs of the War” and “Our Women of the War.”

Detail from “A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac,” Harper’s Weekly, Dec. 21, 1861, p. 808-809

Detail from “Our Women and the War,” Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 6, 1862, p. 568

In the spring of 1862 Homer visited the front again, and this time witnessed actual fighting. He was present in Washington to watch McClellan’s Army of the Potomac embark, and accompanied them on a transport ship to the York Peninsula in preparation for an advance on the Confederate capitol. Homer watched the month-long siege against Yorktown, but left not long after the siege ended. He completed most of his depictions of what he saw there after he returned to New York, and thus ended his stint as a “special artist” for Harper’s. He later complained to his friend John W. Beatty that Harper’s greatly reduced the size of his sketches upon printing them, sometimes squeezing 4 onto a single page and paying him only $25 for the entire page instead of $25 per artwork as was originally negotiated.

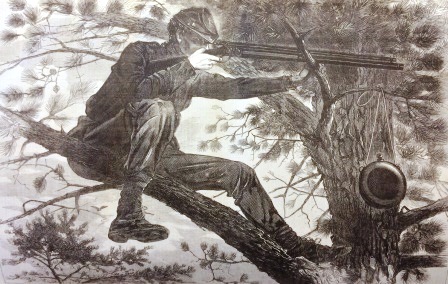

“The Army of the Potomac: a sharp-shooter on picket duty,” Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 15, 1862, p. 724

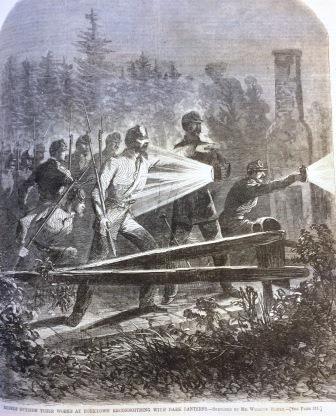

“Rebels outside their works at Yorktown reconnoitering with dark lanterns,” Harper’s Weekly, May 10, 1862, p. 305

Homer’s more famous images of the Civil War, “A Cavalry Charge” and “A Bayonet Charge,” were done after he returned to his home in New York and ended his work with Harper’s. Later drawings of army life suggest that he did make subsequent visits to the front later on in the war, but they were not part of Homer’s official work as a reporter. From here he shifted his focus to painting, although Harper’s did offer him another steady job at the end of his time at the front. Feeling intimidated by his obscurity as a painter, Homer heavily considered taking the job and vowed to his brother that he would accept the offer if his next two paintings did not sell. Unbeknownst to Homer, his brother purchased the paintings himself. Homer did not find out until years later, at which point he “swore roundly and refused to speak to his brother for weeks.” Still, this small encouragement helped to propel Homer into his career as a painter. In subsequent work he depicted scenes from war and soldiers, no doubt inspired by these early sketches.

All prints pictured in this post and more can be seen in their original forms in Harper’s Weekly at the MHS.

—

- Donald H. Karshan and Lloyd Goodrich, The Graphic Art of Winslow Homer, organized by the Museum of Graphic Art, New York, 1968

- Lloyd Goodrich, Winslow Homer, New York: Published for the Whitney Museum of American Art by Macmillan, 1944

- “Biography of Winslow Homer,” Winslow Homer, 2017, winslow-homer.com

- Amy Athey McDonald, “As embedded artist with the Union army, Winslow Homer captured life at the front,” Yale News, 20 April, 2015, http://news.yale.edu/2015/04/20/embedded-artist-union-army-winslow-homer-captured-life-front