By Susan Martin, Collections Services

That word Southwick brings a lot of happy memories to my mind. Can almost see the place now. The old mountain is just beginning to turn color. Chestnut burrs are about half formed and [I] can plainly see the tobacco field with the seed plants standing out like guards.

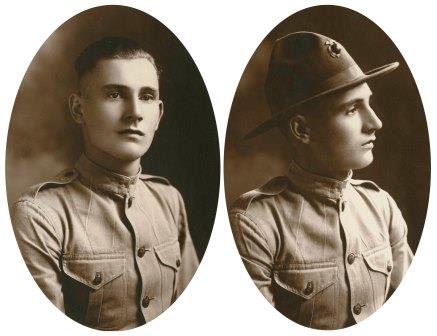

This passage is from a letter written by Private Emerson Phelps Dibble on 25 August 1918, about one month after his enlistment in the U.S. Marine Corps. The MHS recently acquired a fascinating collection of Emerson’s papers, primarily letters written during his service in World War I.

Emerson Dibble was born on 24 March 1898, the son of Albert C. and Winifred E. (Phelps) Dibble. As far as I can determine, he was their only child. Emerson’s mother died when he was just three years old, and his father remarried a woman named Millie Holcomb. The Dibbles lived on a farm in Southwick, Mass., where they grew tobacco.

Emerson enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on 23 July 1918. Most of the letters in the collection were written to his stepmother Millie, his father Albert, and his girlfriend (later wife) Olive Madeline Jordan. Emerson’s letters are detailed, affectionate, funny, and often very moving. For example, when he wrote the words above, he was in training at Parris Island, S.C., and the pangs of homesickness had set in. Being away made him appreciate his home and family more. Millie wrote that she cared for him as if her were her own son, and he replied, “You can never know how my heart jumped when I read that.” He wrote to his father in the same vein:

When I saw and recognised your hand writing Gee, there was that same big lump came up in my throat and then when I read on and saw your feelings [I] couldn’t keep the tears from my eyes. They were tears of gladness tho’ and [I] can tell you this dad that when this big fight is over and I come back up in a decent country and back to Home there is going to be a closer, dearer feeling between us. I’ve made mistakes in the past that [I] never realized until now. You told me hundreds of times that [I] would see them some day but I in a foolish, boyish passion and anger could not see things the way you did. But [I] can assure you that I see them now, and, oh, so plainly, Dad. When I get back you and I are going to be father and son and not strangers as we have almost been.

Emerson seemed to flourish under the rigorous military discipline. He grew fitter and stronger every day, and even qualified as a sharpshooter. He was proud of the toughness of the Marines: “I wouldn’t want to be a Common Soldier. The U.S. Marine is the only real soldier of [the] United States and is good as any other in the world.” Emerson was also full of interesting anecdotes. He described meeting, in South Carolina, “one old fellow who said he was 92. Don’t know whether he was or not. He looked it tho’. He was a slave when the Civil War broke out and he told us he had seen the battle of Cold Springs and also the evacuation and capture of Richmond by the Yankees.”

In September 1918, the Spanish flu epidemic hit Parris Island, and the camp was temporarily quarantined. Emerson had “a slight attack” and recovered, but he was worried about the folks back home. The following month, he shipped out to Europe.

Letters took longer to reach him across the Atlantic, and when he didn’t hear from Millie, Albert, or Olive for three months, he worried even more. He wanted “to have everyone all O.K. when I come home.” But it was Emerson who would get the worst of it. After another bout with the flu and a fever of 103, he was hospitalized with sub-acute bronchitis. He complained of headaches, weakness in his legs, and a cough, but didn’t feel that bad, he said. It was the monotony he hated.

On 1 May 1919, an ecstatic Emerson wrote to Olive and Millie from the U.S. Naval Hospital in Brooklyn, N.Y. He’d been transferred back to the states and still hoped for a full recovery before leaving the service. One letter revealed a new detail: it was tuberculosis that had killed his mother Winifred eighteen years before, and the family was afraid Emerson would contract it, too. He reassured them that he’d had four sputum tests, and all four had come back negative.

Olive and Emerson were now engaged to be married. Olive was a schoolteacher in Springfield, Mass., and Emerson wrote to tell her how much he missed her:

Oh, Olive dear, if you had only known how I longed for you. Just to see you, to kiss you, to feel you cuddle up close to me as you used to. Gee, dearest girl, I lived over a hundred of those fine times we used to have to-gether. […] You understand, don’t you? Guess I have changed some since a year ago. Maybe in some ways for the worse but principally for the good. […] Oh, dearest girl, if you could only feel my feelings now, Olive, I love you, love you – God help me if I ever stop loving you. […] Hoping and praying to be with you and kiss you (again & again) sometime in the near future.

Emerson was honorably discharged from the U.S. Marine Corps on 29 July 1919 with marks of “excellent” for character, obedience, and sobriety. His service was described as “honest and faithful.” In the fall of 1919, before their marriage, Emerson worked at the General Electric plant in Pittsfield, Mass., and wrote often to Olive in Springfield. They were probably married in 1920.

The next letter, the final letter by Emerson in the collection, is heartbreaking. It’s dated 3 February 1921 and was written on stationery from a ladies’ clothing shop in Holyoke, Mass.—Emerson was apparently boarding there after receiving treatment at a sanatorium. His despair is palpable. At the same time, we learn that Emerson and Olive had become parents.

Today I started to “streak” again so I suppose may expect a hemorrhage any time. Hope this one finishes the bell for [I] am sick and tired of this separation and this recurrence of the trouble. Am afraid that I am going to be a misfit and a dependent for life and thats too much for me. […] Have thought of you often and pray for you and the little girl every night. Can’t go to sleep for hours sometimes just thinking of you dear. […] Maybe I am cowardly and all that but am ready to die tonight and would go happy knowing that [I] had taken a load from the world in general.

Emerson died in July 1922 and is buried at Pine Grove Cemetery in Lynn, Mass. According to his application for a driver’s license, filled out earlier that year, he had contracted pulmonary tuberculosis after all.

I’d love to know what happened to his daughter, Peggy Dibble. She was still alive in 1924, but I can’t find any record of her after that. The collection came to us with a small photograph album, but unfortunately the people in the photographs are unidentified. Another unsolved mystery is the location of Emerson’s diary, which ended up in the hands of his friend Mike Cronin and was probably returned to Olive after Emerson’s death.

Amazingly, Olive lived to the age of 94 and died in October 1990. She never re-married and is buried in the Lynn cemetery plot with Emerson.