By Susan Martin, Collections Services

Having spent the last few weeks immersed in a very interesting collection of 19th- and early 20th-century photographs (more on that in a later post), I thought I’d take this opportunity to write about processing photographs here at the MHS and what goes into making these terrific collections available to researchers.

The MHS is primarily a manuscript repository, but most of our manuscript collections come to us with at least a few photographs mixed in. Because of their special storage and preservation needs, the photographs are removed and stored separately. Unfortunately we don’t have the resources to process all of our photograph collections, but we have cataloged many of them in our catalog ABIGAIL, and over fifty are described in more detailed online guides.

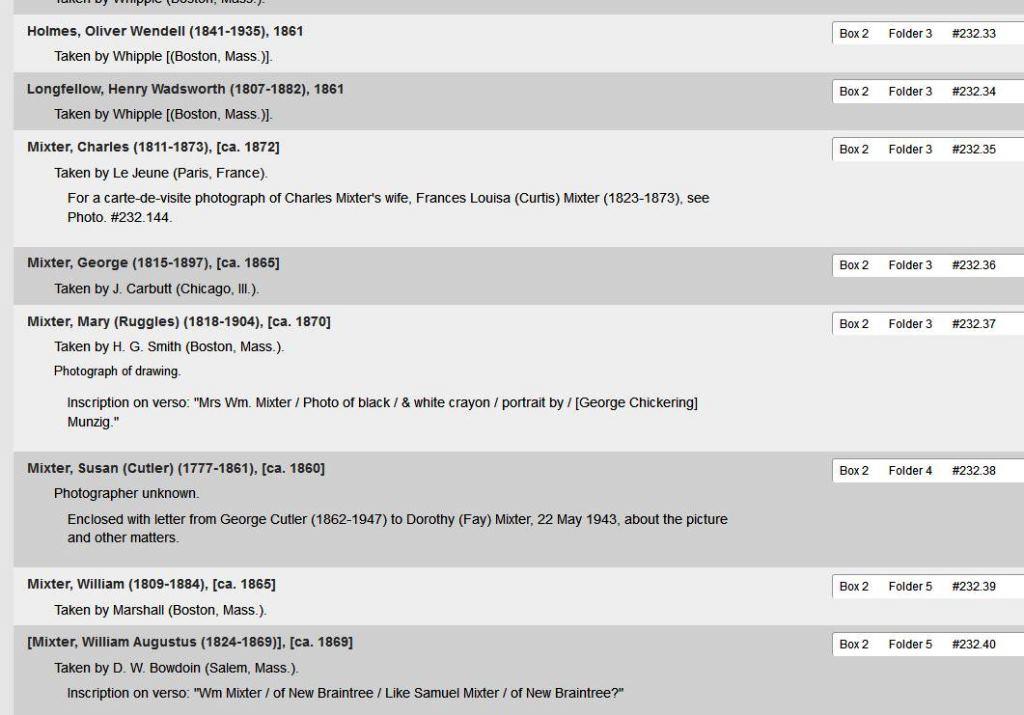

Describing a photograph collection is challenging, and not just because of the technical knowledge required. For one thing, unlike manuscript collections, which are arranged into groups of related material (correspondence, diaries, financial papers, etc.), photographs are described at the item level. Every photograph is listed individually, and each listing includes most of the following information: subject, date, photographer, location, type, size, and condition, as well as any label or caption.

Just the subject and date can be tricky! The collection I’m currently processing, for example, contains hundreds of photographs and came to us completely unorganized. Many of the photographs include no identifying information at all. Since the collection encompasses five generations of a very large family, as well as families related by marriage, I had to do a lot of genealogical research. As I sorted through the photographs, I started to recognize familiar faces (“Hey, it’s Frank!”). My colleague Sabina Beauchard described the fun of making these connections in an earlier Beehive post.

Dates of photographs can be determined—or at least estimated—based on various factors. Here it helps to know something about the history of photography, and fortunately for me (not even close to an expert) our library has some great resources on the subject. If I know when a particular photographic process was invented and when it was most popular, I can make an educated guess about a photograph’s date, even if I can’t identify the subject. I often use “circa” dates and date ranges to hedge my bets.

The earliest photographic processes were metal- or glass-based, and the types I’ve seen most are daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes. Each has distinctive characteristics. Daguerreotypes and ambrotypes both come in cases or enclosures, but a daguerreotype has a mirrored surface, and you have to hold it at a slight angle to see the image. This isn’t true for ambrotypes. And the tintype is the only one of the three that’s magnetic.

Starting in the 1860s, these types of photographs were gradually replaced by paper-based cartes de visite and, later, cabinet cards. These come in standard sizes: cartes de visite are about the size of baseball cards (2.5” x 4”), and cabinet cards are larger (4.25” x 6.5”).

I may be able to use contextual clues to determine the date of a photograph—clothes, hairstyle, etc. If I have multiple photographs of the same person, I can try to guess their age, but this is more of an art than a science! Biographical details are useful: when did they take that trip to Philadelphia? When did they get married? If a photographer printed his or her name and address on a photograph, I can research when the studio was located there. There may even be something in the manuscript collection to help, like a letter the photograph was enclosed in.

Our digital team sometimes comes along behind us and digitizes part or all of a photograph collection, and we link to that content from the guide. Several of our Civil War photograph collections are accessible this way, as are our Portraits of American Abolitionists. Or to find photographs related to a particular person or subject, you can always just search our website. If you can identify anybody we missed, don’t hesitate to let us know!