By Susan Martin, Collection Services

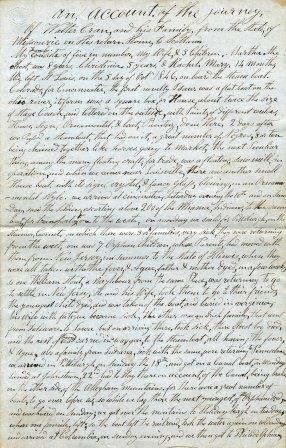

A recent acquisition by the MHS details the harrowing trans-Atlantic voyage of the packet ship Thomas P. Cope in 1846 and, like so many other manuscripts in our collections, touches on several other fascinating subjects at the same time. The seven-page account was written by passenger Walter Cran on 10 January 1847, shortly after the events described. I wasn’t able to learn much about Cran, but he was apparently a Scottish immigrant living in St. Louis, Missouri. He, his wife, and their three young daughters were sailing to Scotland on the Thomas P. Cope, but they never arrived at their destination.

Our story begins a little earlier, though, on 5 October 1846, when the Cran family boarded the steamboat Colorado at St. Louis. As they made their way along the Ohio River, they saw what Cran called “novelties” and “Peculiar things,” including boats that carried sign-painting and glass-blowing establishments and even “a floating saw mill.” Cran also described this chilling sight: “We Passed a steamboat, that had on it a great number of Negros, 8 or ten being chained together like horses, going to Market.” It’s interesting to note that just five years earlier, Abraham Lincoln himself traveled on one of these boats. The MHS holds the letter Lincoln wrote to his friend Joshua Fry Speed on the subject:

In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio, there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border.

In Cincinnati, Ohio, on 11 October, Cran witnessed another notorious American cruelty: “Saw the soldiers, escorting above 200 of the Miama Indians, to the same boat, for transportation to the west.” What he was watching was the forced removal of members of the Myaamia (Miami) Nation from their ancestral home in Indiana, and by all accounts the number actually exceeded 300.

The Crans traveled on, met with some logistical and financial difficulties in Pennsylvania, then boarded the Thomas P. Cope at Philadelphia and sailed for Liverpool. Cran may have thought his hardships were behind him, but the worst was still to come. Late on 29 November, the ship was struck by lightning. Cran described a dramatic series of events:

In a sudden, a loud crack, or crash, was heard like that of a cannon, and a man runs down stairs, crying the ship’s on fire, when Immediately, the smoke rushed so on us, as it darkend the lamp light. I hurridly took hold of my two Eldest Children, & rushed them up stairs, & my Wife brought the baby, naked as they were, and we beheld the main mast and riggin, all in a blaze. A widow woman was halooing, my Child, my Child is below. I attempted to go down for her, but a sailor would not let me. The hatches was Imediately closed for to smother out the fire, for the Lightning had struck the main Mast, went down its centre, into the hold between Decks. […] O the confusion of Capt & sailors, hurring, of the boats over the ship, the women screaming; what a strange feeling I had Putting my family under the low deck of the forcastle, among ropes & blocks, chains &c., for to save them from being killed by Pieces falling from the riggen.

The ship’s main and mizzen masts were lost, and the Cope floated helplessly in the storm. The sea was so turbulent that the first rescue boat lowered over the side was immediately swallowed by the waves, so the frightened passengers and crew decided to stay onboard and try to contain the blaze until sighted by a passing ship. By morning, Cran wrote, some women “laying on the quarter Deck […] had their hair froze to the deck.” His own family huddled in the bow: “Hard times they had, for when the waves broke over, they were wet, and the sails of the fore mast, taring to ribbons, cracked over their heads, like thorns, a blazing, the snow & the hail attending.”

Amazingly, the passengers and crew managed to contain the fire and avoid sinking for almost a week. On 5 December, the Thomas P. Cope was spotted by a ship sailing from Liverpool—the Emigrant. Its crew effected a daring rescue, transferring passengers from ship to ship on small boats in the rough seas. Safe onboard the Emigrant, Cran and the others watched the Cope disappear in “a perfect cloud of smoke.” All but one of its passengers had survived—the widow’s six-year-old daughter trapped below deck in the initial chaos.

The Emigrant was sailing in the opposite direction, back to North America, and took their new passengers with them. With the help of that ship and another called the Washington Irving, the Cran family made it to Boston on 20 December 1846. Unfortunately, they had lost all their money and belongings. Walter Cran acquired some supplies from philanthropic individuals and societies, probably including the Scots’ Charitable Society (the MHS holds some material related to that organization). But the devastation of recent events caught up with him, and he wrote that he “could not help washing my face with my tears.”

Cran finally made contact with another Scottish immigrant, the wealthy merchant Robert Waterston. Waterston and his stepsisters, “the Misses Ruthven,” invited the penniless family to their home in Boston’s Fort Hill neighborhood. Cran described their hospitality with gratitude: “When we arrived, the first words the Ladies said to us, was; your welcome here. They set us by a large fire, and gave us breakfast, Plenty of water to wash with, and clean clothes to put on.” The Crans stayed there a week, until the Waterstons found Walter a job and put him “in a fare way, for to Provide for my Family again.”