By Katherine Green, Reader Services

In March, Brendan Kieran from Reader Services wrote a blog post about industrial labor unions in Boston. This month, while browsing through ABIGAIL, I happened upon echoes of a very different kind of union history: that of the Western Federation of Miners and the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903-1904. The WFM, formed in 1893, sought to bargain for the rights of miners whom they felt were being exploited by rich mine owners.

The Massachusetts Historical Society collections, despite our East Coast location, is connected to the mines and miner strikes of Southwestern Colorado through the journals of Robert Livermore. His personal papers include a collection of neatly penned memories decorated with photographs and original pen-and-ink drawings.

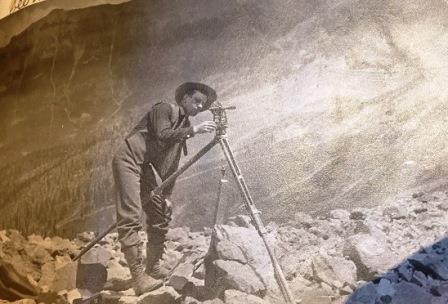

Robert Livermore surveying in Colorado

Livermore, who grew up in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts and attended Boston Latin School, Harvard University, and MIT, journeyed out west in the early 1900s to travel and to work for the mines owned by his brother-in-law, Bulkeley Wells. Livermore arrived at Camp Bird Mine in Ouray, Colorado on 27th June 1903 to survey and sample the rock formations.

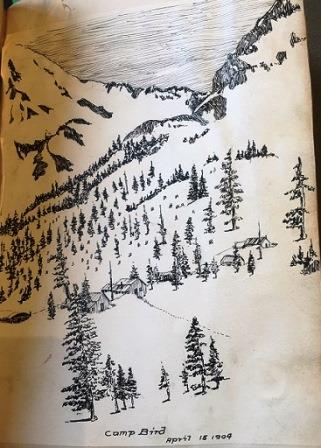

A sketch of Camp Bird drawn by Robert Livermore

In his journal, he describes the combination of “luxury and wilderness” Camp Bird Mine boasts:

We live in a great wooden building with baths, hot water, and electric lights, the best of wholesome food and fresh creamy milk, and all around us is the great wilderness of spruce forest and jagged peaks as it was since time immemorial.

Livermore’s brother-in-law Bulkeley Wells, whom he affectionately refers to in his diary as ‘Buck,’ was a businessman and manager/owner of Smuggler Mining Company in Telluride. Between his mine in Telluride and Camp Bird Mine in Ouray, there was much unrest among miners, mine labor unions, and mine owners. Wells himself was often at the forefront of anti-unionist attacks. According to a Daily Sentinel article, Wells led a mob of townspeople to ransack buildings to find and force out union members.

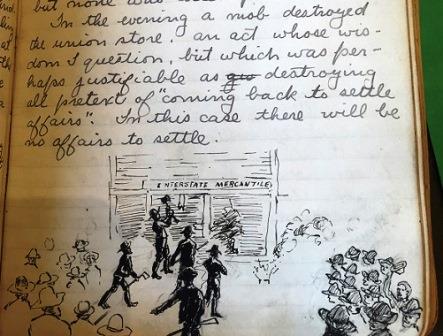

Meanwhile, Livermore seemed to enjoy his work in and around the mines, though he makes numerous observations of men who were killed or maimed in the harsh working conditions. “Yesterday Jessey, the shift boss was caught in a cave-in, in 327 stope but luckily escaped with only a broken leg.” (A stope, according to Merriam-Webster, is “a usually steplike excavation underground for the removal of ore that is formed as the ore is mined in successive layers.”)

Livermore himself suffered injuries from his work:

On Saturday the 18th, my eye became very much inflamed from a piece of steel or rock which had lodged in it while sampling. I went to Ouray and had it looked to by the local doctor. He could find nothing in it at first, but that day discovered the substance in the middle of the pupil and extracted it, supposedly.

In an entry dated 21st August 1904, Livermore describes an army of hundreds of anti-unionists descending upon Cripple Creek:

I never saw a more impressive sight than these hundreds of quiet, determined Americans, with their dinner buckets in hand, each with a revolver on his hip, making no display but resolved to suffer no more from the murderous gang who have tyrannized over them so long.

Livermore details the army’s actions of overpowering the union store and marching its members out of town. Later that evening, the union store was destroyed by a mob – an act which Livermore questions in his diary. Perhaps he did not share the sentiments of Buck, who seemed to relish the power and force he could exert over the unionists.

In his writings, Livermore appears fiercely attached to his sister and, by extension, his brother-in-law. Besides this loyalty to the anti-unionist Buck, and in spite of the fact that he uses a phrase like “murderous gang” to describe the union members, Livermore appears to be a passive observer in these conflicts.

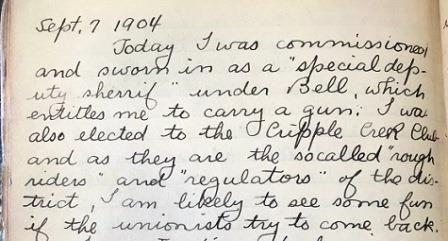

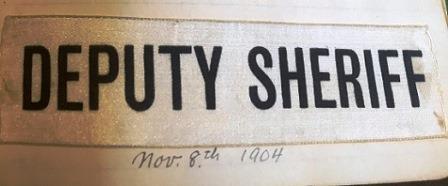

“Today I was commissioned and sworn in as a ‘special deputy sherrif’ [sic] under Bell, which entitles me to carry a gun.”

This changed in September 1904. Under Adjutant General Sherman Bell, Livermore was appointed “special deputy sheriff” in Colorado’s government-backed anti-union forces. In one journal entry, he celebrates that he’ll be allowed to “carry a gun” and that he is “likely to see some fun if the unionists try to come back.” Perhaps his brother-in-law’s influence won out in the end.

A photograph of Livermore’s “Deputy Sheriff” insignia

After the strikes ended at the close of 1904, Livermore would go on to invest in and run numerous mining companies. He retired to Boxford, Massachusetts and died in Boston in 1959.

If you would like to learn more about Robert Livermore and his life, you can visit our library. You can also find related materials at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center.