By Susan Martin, Collections Services

Elizabeth Elliot Mixter was born in Boston on 24 January 1913. She was the oldest child and only daughter of renowned neurosurgeon William Jason Mixter and his wife Dorothy (Fay) Mixter. Like other young women hailing from the elite Brahmin families of Boston, coming of age meant a “debut” into society at around the age of 18. Elizabeth’s debut took place in the fall of 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression.

The MHS collection of Fay-Mixter family papers contains a large scrapbook of newspaper clippings, programs, invitations, photographs, and other papers documenting Elizabeth’s ”Coming Out Year 1932-1933.”

Elizabeth made her official debut on 9 November 1932 at a tea held in her honor by her grandmother, Elizabeth Elliot (Spooner) Fay, at 330 Beacon Street. Pourers at the tea included other young ladies from the so-called “smart set.” Many of their names are recognizable—for example, Polly Binney, whose family’s papers are located right here at the MHS, just a few shelves away from Elizabeth’s. Another pourer was Abigail Aldrich, none other than the niece of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

Elizabeth’s cousin Anne Mixter, also one of that year’s debs, couldn’t make it to the tea because of an emergency appendectomy. Neither could “plucky” 17-year-old Frances Proctor, who’d been mugged just two days before and apparently punched in the mouth when she refused to surrender her car keys. Frances’ story is told in a newspaper clipping entitled “Society Girl Is Beaten by Holdup Man.”

According to the Boston Evening Transcript of 4 June 1932, more than 150 debutantes were formally presented in the 1932-33 season in Boston, an “unusually large” number. After coming out, a deb’s life became a whirlwind of parties, dinners, concerts, costume balls, charity events, etc. Elizabeth was invited to join exclusive clubs like the Junior League of Boston and the Vincent Club. She took part in theatrical performances and studied cooking and home economics.

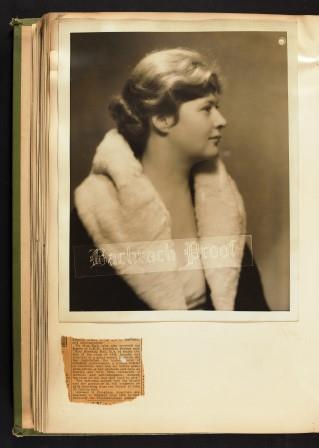

A deb was photographed, or “snapped,” around town, and the society pages detailed her clothing and appearance. For example, on their way to a luncheon, two young ladies were “nicely turned out in their new fall costumes, so modishly trimmed with fur.” Polly Cunningham was described as “the luscious, rounded type with golden curls and merry blue eyes, beautifully poised and magnetic.” And here’s what one article had to say about a roller skating party: “One of the prettiest of the skaters was Miss Elizabeth E. Mixter of Brookline. Like many others, she took dainty falls but enjoyed the frolic.” Another writer used the word “pulchritudinous.”

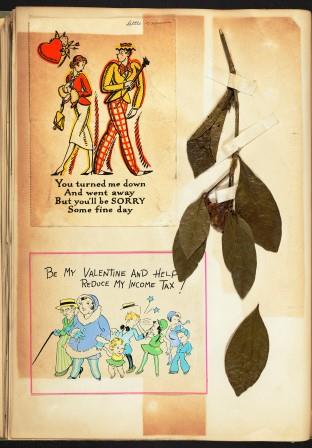

Amidst the high-society gossip and fashion tips are a few hints of the tough economic times then plaguing the country. One page of the scrapbook contains a re-written version of Psalm 23 that begins: “The politician is my shepherd – I am in want / He maketh me to lie down on park benches.” Also included is an article entitled “Depression Debutantes,” from the 12 November 1932 Saturday Evening Post, which makes the argument that “coming out” prepares a young woman not just for marriage, but also for work. Perhaps most revealing, Elizabeth filled out an elaborate budget sheet, probably as part of her home economics coursework, detailing how to save money on clothing purchases over three years.

As for the uncomfortable premise of the whole debutante phenomenon—the marketing of young women of a certain social standing as eligible marriage prospects—Elizabeth’s scrapbook has that covered, too. It includes a column from the gossip magazine Tatler and American Sketch by an anonymous author, aptly named “Audacious.” In the column, Boston debs are sorted into “grades” based on, well, the blueness of their blood.

Grade A includes Abigail Aldrich and Polly Cunningham, as well as Misses Appleton, Coolidge, Hallowell, Holmes, Jackson, Lawrence, Loring, Peabody, Perkins, Saltonstall, Shaw, Winthrop, and others. Elizabeth, her cousin Anne, and Polly Binney are all listed in Grade B. “Plucky” Frances Proctor rates Grade C, though I would argue she deserves much higher!

The mercenary nature of these rankings shocked some contemporary journalists. When the Tatler and American Sketch went out of business in January 1933, editor John C. Schemm, outed as the author of the column, said: “I meant that department to be a constructive force, but it can’t be done. No matter how intelligently you strive to do the job, or how constructively, you cannot avoid creating hard feelings.”

Elizabeth E. Mixter married Dr. Henry Thomas Ballantine, Jr. in 1938, and the couple had two children. She died in 1998.