By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The MHS just acquired a fascinating document related to political activism by Boston’s black voters during the 1884 presidential election. This election, only the fourth presidential contest in which black (male) voters could take part, pitted Democrats Grover Cleveland and Thomas A. Hendricks against Republicans James G. Blaine and John A. Logan. Most African Americans supported the Republican Party, and “Blaine and Logan Clubs” had sprung up in many American cities, including Boston.

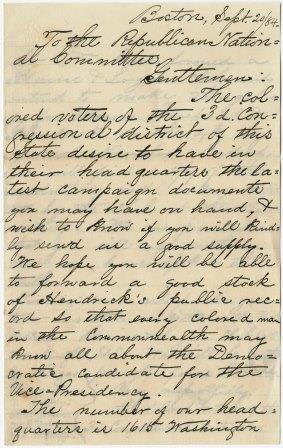

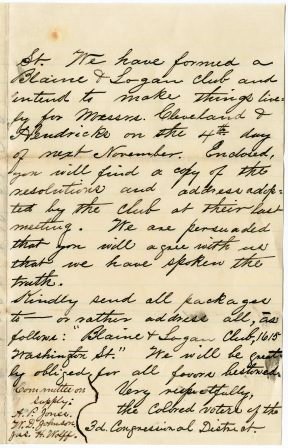

On 20 Sep. 1884, a committee consisting of three Boston men sent this letter to the Republican National Committee on behalf of the “colored voters of the 3d. Congressional district” of Massachusetts. They requested information on the candidates, particularly Democratic vice presidential nominee Hendricks. The letter reads, in part:

We hope you will be able to forward a good stock of Hendrick’s [sic] public record so that every colored man in the Commonwealth may know all about the Democratic candidate for the Vice-Presidency. […] We have formed a Blaine & Logan Club and intend to make things lively for Messrs. Cleveland & Hendricks on the 4th day of next November.

I was curious about this “opposition research” targeting Hendricks. Thomas Andrews Hendricks (1819-1885) of Indiana certainly had a substantial public record. By 1884, he’d served in multiple elected offices, including state congressman, U.S. representative, U.S. senator, and governor. He’d even run for vice president once before, on a ticket with Samuel Tilden in 1876, but they lost to Rutherford B. Hayes. So, what specific grievances did black voters have against Hendricks? To answer that question, I found two terrific resources in the MHS stacks, both printed in Boston in 1884.

The first is a book called The Life and Public Services of Grover Cleveland, by Frederick E. Goodrich, which includes an appended biography of Hendricks. Goodrich was an enthusiastic Democrat, and his biography is unabashedly partisan. He describes the Democrats as the true heirs to the Founding Fathers and calls the Republicans “demoralized” and “thoroughly corrupt.” Hendricks himself sounds almost mythical: “His honesty was above suspicion, his integrity was never questioned, nor his motives impugned. He won the respect of all his colleagues and retained the confidence and support of his constituents.”

Goodrich wrote in generalities and didn’t have much to say about Hendricks’ specific votes related to slavery or African American civil rights. He did explain, in one passage, Hendricks’ support for the Fugitive Slave Act:

It has been objected to him lately, that he was in favor of the Fugitive Slave Law; but so was the majority of his party, which at that time recognized that slavery was a legal institution in the Southern States, and which upheld the right of the slave-owners to claim their property wherever they found it. It is too late in the day now to rake up the anti-slavery record of any man, because many of our foremost and most honored public men since the war were, prior to that event, defenders, or at least apologists of slavery.

The second resource I found at the MHS was a speech by W. R. Holloway delivered on 2 Aug. 1884 and published in pamphlet form as A Bad Record: Hendricks as a Public Man. William Robeson Holloway (1836-1911), a staunch Republican and brother-in-law of Gov. Oliver P. Morton, had held various political appointments in Indiana. He was a full-throated anti-Hendricks man and didn’t mince his words, characterizing Hendricks like this:

Shown to have been the Friend and Apologist of Slavery, a Copperhead of the worst type.—An Intense Negro Hater, as well as a Defender of Treason, a Constant Sympathizer with the Rebellion.—The Champion of Traitors, and always a Bogus Reformer, an Insincere Demagogue, and an Uncertain Leader.—Not a Redeeming Feature to be found in the Public Career of the Choice of the Democracy for Vice-President.

Hendricks did, in fact, oppose all three Reconstruction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution: the Thirteenth (abolishing slavery), Fourteenth (extending citizenship, due process, equal protection, etc.), and Fifteenth (granting suffrage to black men). In his speech, Holloway also described how the Democrat “sustained and defended the Dred-Scott decision,” “denounced the Emancipation Proclamation,” and opposed the military service of African Americans, arguing that black soldiers lacked the courage to serve alongside whites. He accused Hendricks of opportunism, hypocrisy, and cowardice. Here’s more:

He has been consistent in his opposition to the negroes, and while in the Senate, voted uniformly against the colored race, against emancipation in the District of Columbia, against their civil and political rights in that District, and against their right to ride on the street-cars in the city of Washington; opposed their employment as soldiers, and after they were enlisted and had gallantly perilled their lives on the field of battle, he voted on more than one occasion to deny them equal compensation with white soldiers in the same service.

It’s no wonder the “colored voters of the 3d. Congressional district” were determined to “make things lively”! Massachusetts’ 14 electoral votes went to the Republican nominee, James G. Blaine, but despite the party’s best efforts, Grover Cleveland won the election by a narrow margin. Thomas A. Hendricks died one year later on 25 Nov. 1885, and the vice presidency remained vacant for the rest of Cleveland’s term.

I hoped to find out more about the three men who sent the letter, A. P. Jones, W. D. Johnson, and Jas. H. Wolff, but could only definitively identify the third man. The remarkable story of James Harris Wolff (1847-1913) probably deserves a blog post of its own. He served in the Navy during the Civil War and became a prominent black attorney who argued civil rights cases for African Americans. In 1910, he was the first black person to deliver the official Fourth of July oration in Boston.