By Sara Georgini, Adams Papers

The skeletons and the state representative first met on a warm fall afternoon in West Medford, 1862. Two day-laborers, sifting the topsoil with an ox-shovel, nearly hit bone. They ran to alert landowner Francis Brooks, a well-known lawyer and amateur naturalist. Peering over the pit in his backyard, Brooks saw raw history sewn into the earth below: five skeletons, some loose iron arrowheads, a costly-looking soapstone and copper pipe. The Brooks family had held the land—once as vast as 400 acres, now 50—since 1660, and the Native Americans lying before him all dated from the early seventeenth century.

The largest skeleton, as Francis thought, might even be that of Wonohaquaham (d. 1633).

A sachem better known as “Sagamore John,” Wonohaquaham once governed the swath of settlement that spanned Charlestown and Chelsea. Within Boston’s circle of gentleman scholars, Francis Brooks’ local find made a ripple of news. The Massachusetts Historical Society published a detailed account of the “Indian necropolis” found near Mystic Pond.

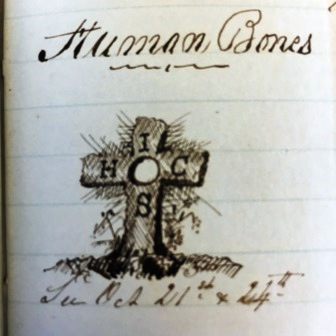

“I admit. I am all excitement for more bones,” Brooks wrote in his farm journal on 21 October. “I have now two baskets full which ornament the entry table. By and by they shall be put back to rest. With some stone over them in the old place.” Exercising “intelligent care,” he and wife Louise bundled up the bones and carried them across the Charles to a Harvard friend, Louis Agassiz, for use in his new museum of comparative anatomy. Unfazed that his ancestral estate was planted squarely in the half-hidden heart of a Native American burial ground, Francis Brooks quietly returned to farming and law.

But, when he could, Brooks (1824-1891) dabbled in digging around for ancient history. Growing up in Boston, Brooks read the eclectic popular science offerings in the antebellum press. Newspaper squibs of archeological finds and snippets of scientific lore laced through his daily headlines, alongside word of abolition, women’s rights, secession, and Civil War. Many of the articles that he saw dealt with gauging the earth’s age, by tweaking geology to conform with Protestant Christianity. Headlines included the race to decode Egyptian hieroglyphics, and the rise of learned societies to stir up “science talk.” Like many Victorian Americans who spent the century rooting around in the distant past, Francis Brooks’ first efforts were amateur but diligent. He joined a vanguard of “citizen scientists” who kept weather diaries, went on naturalist hikes, funded new museums, lingered in private “bone rooms,” and marveled at “wonder shows” of ancient mummies.

To men and women like Francis Brooks, modern science served as spectacle and oracle. Armed with the private money and public momentum needed to launch new institutions, urbane Americans like Brooks made popular science thrive, on and off the printed page. The Boston Society of Natural History opened its doors in 1830 and evolved into the modern Museum of Science. The Society swept up human crania, skeletons, botanical specimens, and a glittering array of raw minerals. At Ford’s Theatre, a floor above the box where John Wilkes Booth shot President Abraham Lincoln, curators lined shelves with specimens in 1866, forming the Army Medical Museum . But as the war claimed lives within Francis Brooks’ hometown ranks, his gaze moved past backyard finds. With Civil War America encased in ashes daily, Brooks’ focus pivoted to ancient Pompeii.

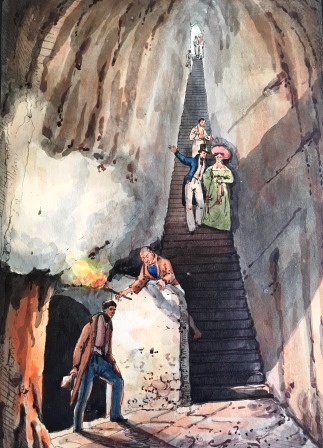

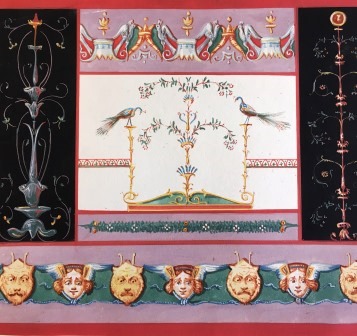

What did early Americans know of Pompeii’s history and story? From afar, Brooks and his antebellum peers savored the historical snapshot of a lush city, frozen in fallen glory. In August 79 A.D., the eruption of Mount Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum, swiftly burying residents and homes in 13 to 20 feet of volcanic ash. Such a sudden loss ripped at the ancient region’s heart. Staring hard through the toxic smoke barreling across the Bay of Naples to his evacuation point, Pliny the Younger said that it was “as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room.” Centuries’ worth of writers, ancient and modern alike, wrote and reframed the tragedy. By 1599, archeologists began excavating the towns’ riches. Looters followed. Overall, they found stray wine bottles, an aqueduct, bath-houses, and villas packed with papyri. Rose-red and evergreen-tinged frescoes filled the halls where 11,000 Pompeiians had lived and loved, worked and died.

For Americans like Francis Brooks, who studied Latin and Greek classics, Pompeii was a scientific goldmine. Hiking the partially excavated city was a “must” on the grand tour of fashionable gentlemen and adventurous debutantes alike. Pompeii’s fossils of vice–brothels, pagan temples, slave chains–intrigued Victorian reformers championing temperance, Protestant values, and abolitionism. In the early 1870s, as part of a philanthropic mission through Europe, Francis Brooks finally made it to see the distant past in person. At home, he kept farm journals documenting crop growth, his children’s birthdays, and the Brahmin party circuit. Once abroad, Brooks started (briefly) a thick sketchbook, “Views of Pompeii,” held here in the Massachusetts Historical Society. There, Brooks copied foreign frescoes in precise, vivid gouache. Under his brush, the city’s half-eaten columns again soared up to a calm sky. Brooks posed his travel companions in parlor-room vignettes, making 80 paintings in total. Pompeii’s exotic panorama of pagan altars, opal sunsets, and fantastic beasts, supplied Francis Brooks with a rich backdrop for his art–and a new way to see how monuments can embody memory.

Early in autumn 1882, the skeletons and the state representative met for one last time. Several of Francis Brooks’ workers, busy digging a cellar on the West Medford estate, came upon roughly 18 Native American skeletons, including that of “Sagamore John.” Brooks’ rage for “more bones” had quieted a bit after seeing Pompeii. When he gazed out over the family grounds, Francis Brooks saw rows of potatoes and corn, plus a 70-foot-long brick wall built by slaves 200 years earlier. He added a plain granite monument, inscribed, “TO SAGAMORE JOHN AND THOSE MYSTIC INDIANS WHOSE BONES LIE HERE.” Lessons from ancient history, as Brooks learned in Pompeii, still guided modern steps.