By Rhonda Barlow, Adams Papers

In the spring of 1787, two men wrote to America’s representative in London recommending naval inventions that they thought would help the United States fight the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean. One of those writers was Andrew Quin, a gunner aboard the Dutch warship, Batavier; the other was Patrick Miller, a Scottish banker and inventor who experimented with cannons, water wheels, and steam power. The American representative just happened to be John Adams, then serving as American minister to Britain.

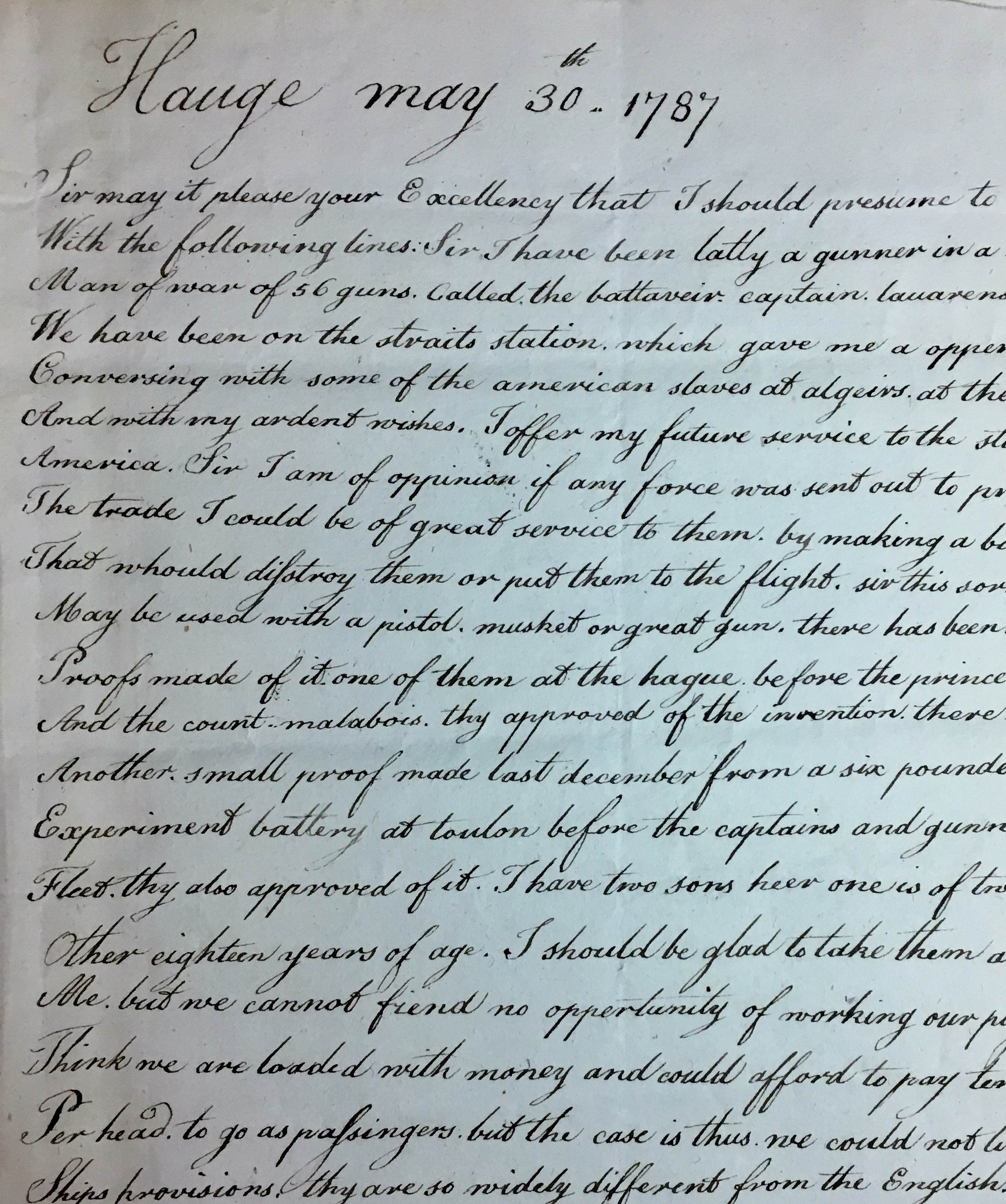

In his 30 May letter, Andrew Quin recommended that American warships use “burning shot” as effective ammunition against the Barbary pirates, and offered his assistance:

“Sir I am of oppinion if any force was sent out to protect the trade I could be of great service to them. by making a burning shot That whould disstroy them or put them to the flight.”

“Burning shot,” more commonly known as “red-hot shot,” or simply “hot shot,” refers to cannonballs that were heated in a furnace before being loaded into the cannons and fired. These cannonballs not only damaged a ship, but threatened to set it on fire.

Quin also told Adams about his two sons, his financial troubles, and the challenge of emigrating to America. He wrote with a legible hand, and although the words do not rhyme and the sentences flow across the page, he imitated the poetic convention of capitalizing the first letter in each line.

Adams was familiar with the Batavier and with her former captain, Wolter Bentick, who died from the wounds he sustained during the 1781 Battle of the Dogger Bank between the Dutch and British navies. But he had probably never heard of Quin, and this letter appears to be the only letter Quin wrote to John Adams. We have no reply from Adams, and found no evidence that Adams took any action beyond retaining the letter.

In contrast, there are two letters to John Adams from Patrick Miller, who was experimenting with steam propulsion for navigation. With his 14 April 1787 letter, Miller included an essay on naval architecture: Elevation, Section, Plan, and Views of a Triple Vessel (Edinburgh, 1787); and on 30 April, Adams wrote a short note to him:

“I have received the elegant volume you did me the honor to address to me, and shall take the first favorable opportunity to transmit it to Congress at New York, in conformity to your desire.”

Adams took action, forwarding the essay to Congress. On 19 Nov. 1787 Miller wrote to Adams again, and included a report describing his experiment in the Firth of Forth, near Edinburgh, Scotland, on 2 June, when a ship reached speeds of over four miles per hour as five men operated a winch connected to his water wheel. In further experiments, Miller employed a steam engine and achieved speeds of 8 miles per hour.

Miller had already made improvements to a light and effective cannon, the carronade, and wrote that ships outfitted with paddle wheels, and thus capable of propulsion regardless of the lack of wind, were America’s answer to the Barbary pirates:

“Five or six such Ships would clear the Seas of all the African Cruizers.— In Calms or light Winds, very frequent in the Mediterranean Sea during the Summer Months, they would be superiour to any number of Ships of the present Construction of whatever force—”

Adams forwarded Miller’s report to Congress too. Based on Adams’ interactions, Miller’s letters will appear in the Papers of John Adams, volume 19 (Belknap Press, HUP, 2018), and Andrew Quin’s will not. But omitting the letter does not mean that we discard it. Andrew Quin’s original letter remains in the Adams Family Papers archive. You can view the manuscript on the Adams Papers microfilm, reel 370. A rough transcription is freely available on Founders Online.