By Alex Bush, Reader Services

As November wears on and the weather grows colder, many Bostonians are digging their coats and sweaters out of storage in anticipation of the long winter ahead. As if winter isn’t long enough already, imagine for a moment that temperatures started to drop in May instead of November. In April of 1815, the eruption of the volcano Mount Tambora rocked modern-day Indonesia. The blast, nearly 100 times as large as that of Mount St. Helens in 1980, sent a massive cloud of miniscule particles into the atmosphere. As the particle cloud blew its way around the globe it reflected sunlight, causing a meteorological phenomenon to which we now refer as the “year without a summer.”

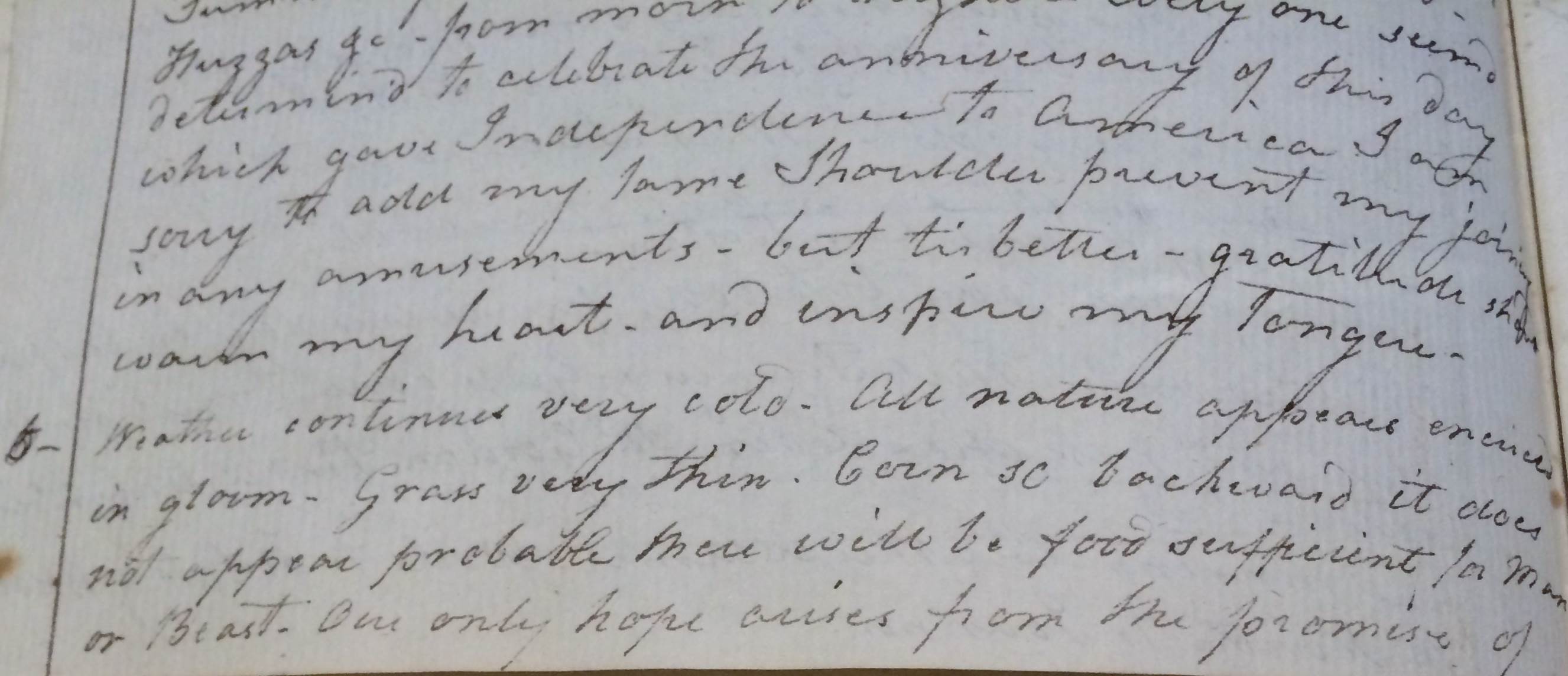

From May to August of 1816, weather across the globe was unseasonably cold. It regularly snowed in New England and London was pelted with hail. It was during this freezing volcanic winter that Mary Shelley drafted the dark tale Frankenstein while on holiday in Switzerland. In his daily diary entry from July 4th of 1816, John Quincy Adams complained that he was confined to his house in London all day due to freezing rain showers and thunder. Many of his subsequent entries that summer contain similar lamentations.

There was Thunder at intervals, and Showers of rain almost incessant through the whole day… I attempted a walk; but was twice overtaken with Showers ingoing to Ealing Church and returning.

While scientists are now nearly positive that the “year without a summer” and Mount Tambora’s eruption are connected, it took until the 1970s to piece together the clues. Many people at the time blamed the volatile weather on sunspots, having seen more than usual leading up to the cold snap. By looking back at patterns in sunspots, scientists now hypothesize that while Mount Tambora’s eruption happened to coincide with the appearance of several large sunspots, the two phenomena were not connected. It is also possible that the eruption’s resulting haze allowed for easier viewing of the sun without the aid of eye protection, which led more people to notice the spots and connect them to the odd weather.

Hannah Dawes Newcomb, who endured the freezing summer weather with her family in Keene, New Hampshire, kept a diary with short daily reports on her everyday life. Starting in around May, her daily comments on the weather start to reflect the strange weather patterns of 1816.

May, 1816

13 – Cold but pleasant.

14 – Cold weather.

15 – Very cold.

16 – The weather remains very cold.

17 – Very cold, have to keep a large fire in the parlor to keep comfortable.

18 – Very hard frost last night, very cold this morning.

19 – Very cold for the season.

By July, things only get worse for the family. Newcomb seems especially concerned with the constant need to keep a fire going in the hearth. Throughout June and July, she complains of crops freezing on the vine and farm animals dying from the cold. In late July, she mentions seeing sunspots after attending church with her family.

July 6 – “Weather continues very cold – all nature appears encircled in gloom – Grass very thin. Corn so backward it does not appear probably there will be food sufficient for man or Beast. Our only hope arises from the promise of seed time and Harvest. We daily keep fire in the parlor.”

Elsewhere on the East Coast, the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture held an October 1816 meeting following the destructively cold summer. The Society’s curators resolved to compile and distribute a newsletter that would aid farmers in selecting and cultivating crops that could best survive the cold, as well as provide instructions in the event of future “uncommon occurrences.”

In performing this useful service, [the Curators] will designate the Trees, Grasses, and other Plants, and especially those cultivated, on which the Season has had either beneficial or injurious influence, and the local situations in which it has operated more or less perniciously, with the view to ascertain, (among other beneficial results,) the hardy or tender Grains, Grasses, or Plants, more proper for situations exposed to droughts, wet, or frost.

Relevant MHS materials:

At a Special Meeting of the ”Philadelphia Society for promoting agriculture” October 30th, 1816

Other sources

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/science/mount-tambora-volcano-eruption-1815.html?_r=0

The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History, by William K. Klingaman and Nicholas P. Klingaman