By Laura Wulf, Collections Services

The Digital Projects team here at the MHS has spent much of the past two years working on an LSTA funded project that we are calling “Women in the Public Sphere.” This grant allowed us to fully digitize and make accessible seven collections related to women’s involvement in social issues of the 19th and early 20th centuries, including the suffrage and anti-suffrage movements, education, poverty, anti-slavery and pacifism.

The collections range in size from 11 items in the Juvenile Anti-Slavery Society records, 1837-1838 to more than 3000 items in the Rose Dabney Forbes papers, 1902-1935. In this post, I will take a closer look at the Forbes papers, which document the participation of Rose Dabney Forbes (1864-1947), the wife of businessman J. Malcolm Forbes (1847-1904), in the American peace movement of the early 20th century, as an officer of the Massachusetts Peace Society, the American Peace Society, the Massachusetts branch of the Woman’s Peace Party, and the World Peace Foundation. The records of the organizations in which she was involved include governance documents, meeting minutes, and correspondence, as well as printed materials.

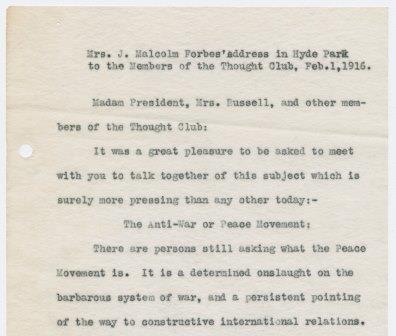

In a typescript draft of an address delivered to members of the “Thought Club” in Hyde Park, Mass., by Mrs. Forbes on 1 February 1916, she argues for the “necessity of extending the reign of law out from the smaller circle of nationalism, to the larger circle of internationalism.” Forbes goes on to write that,

Irrespective of opinions as to the causes, and as to the consequences of this terrible European war, thinking persons who stand for Twentieth Century ideals are passionately exclaiming that this shall be the last war between civilized nations; that the world after this shall not allow such a method for trying to settle international differences.

Speaking as a representative of the Woman’s Peace Party, Forbes asked why the peace movement “is still imperfectly understood even by many persons who are distinctly in sympathy with its fundamental object.” Was it because the war is happening overseas, leading to what she called “[m]ental inertia”? Was it because of a “[l]ack of literature giving authoritative and complete statement of what a great body of leading internationalists believe,” or because, as she suggested, the press ridiculed the ideas as well as the movement?

She addressed what she calls a misconception that “when we work to banish the war system from earth, we are lowering the heroic ideals of manhood- that we are training our boys to be timid and slothful-to be ‘molly-coddled. No indeed” she exclaimed, “we train our boys to be ready to die for their country, by serving humanity, not by destroying their human brothers.” Lastly she asked whether it could be that the very name of the movement had held it back. “The word Peace,” she wrote, “stands for the result of justice and righteousness; peace is an effect, not a method of working force. Only in a restricted sense of the word is peace simply cessation of war.”

As part of her call to action, Forbes quoted Phillips Brooks, Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Ellery Channing, and she summed up her argument by insisting that

The truth is that the war against war is and has long been an aggressive campaign of education. The Peace Movement is a determined onslaught on the old and barbarous system of war, and a persistent pointing of the way to constructive international peace. The Peace worker must summon all the logic and clearness of thought that he can command and he must needs stand firm in his faith, not heeding either the ridicule or the sneers of the unconverted.

How do peace movements of today articulate their hopes and strategies? We encourage you to look through these newly digitized collections and make your own comparisons and discoveries.

For more of the story, check out part 2 of Rose Dabney Forbes and the American Peace Movement.

*****

Funding for the digitization of this collection and the creation of preservation microfilm was provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act grant as administered by the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners.