By Susan Martin, Collection Services

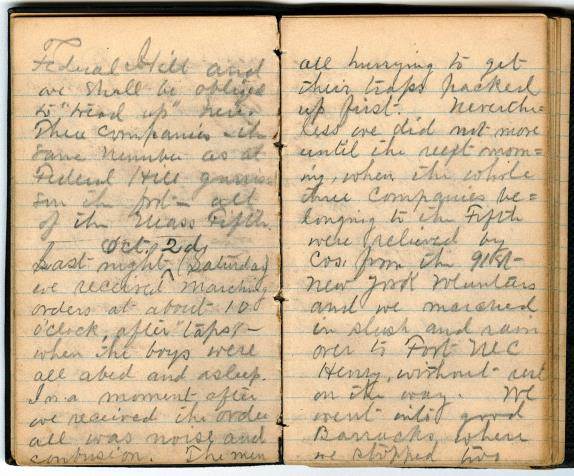

The Civil War diary of Joseph Warren Phinney, a recent acquisition of the MHS, is a small unassuming leather volume. Probably fewer than half the pages are covered with smudged pencil entries dated 13 July 1864-22 April 1865, as well as miscellaneous memoranda. But even a cursory look into its contents reveals fascinating details.

Phinney hailed from Sandwich, Mass. and served with the 5th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Company A. His diary complements our other holdings related to this regiment, which include the papers of Charles Bowers, William Wallace Davis, Benjamin Newell Moore, and George L. Prescott. But it was Phinney’s entry of 8 October 1864 that piqued my interest. It begins: “To-day I was detailed to go with a squad to protect the Polls in a small town on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.” October was too early for the presidential election, but Phinney didn’t provide any context, so I consulted Alfred S. Roe’s 1911 history of the regiment to learn more.

Phinney was, in his small way, taking part in a momentous day in Maryland’s history. The Emancipation Proclamation had freed slaves in the Confederacy nearly two years before, but Maryland had never seceded and so was still a slave-holding state. In fact, its 1851 Constitution explicitly outlawed “any law abolishing the relation of master or slave.” October 1864 saw Marylanders voting to ratify a new constitution which would, among other things, abolish slavery in the state. (It ultimately squeaked by with a tiny majority of 375 votes.)

The 5th Massachusetts Infantry sent several squads from Baltimore’s Fort McHenry down the Chesapeake Bay to protect polling places along the Eastern Shore. Phinney’s squad was detailed to the small town of Trappe in Talbot County. They were quartered there for about a week, first in a schoolhouse and then a church.

But this 19-year-old bachelor wasn’t thinking about his place in history. He wrote: “We received many favors from the inhabitants and lived high on sweet potatoes and johnny cake brought in by them. The boys had plenty of liberty and improved it by seeing all they could and tasting all they saw.”

If you sense a certain tone to his words, you’re not imagining things. After his return to Baltimore, Phinney elaborated: “How much I enjoyed my visit at Trappe I can’t well express, but a long letter, containing three closely written sheets of good sensible sized note paper seems to tell me that I wan’t the only one who remembers with pleasure my visit to the ‘Eastern Shore.’” His correspondent was someone named either Emma or Erma—I can’t quite make out his handwriting. Whoever she was, he called her “darling” and “a good sweet little dear” and cherished her “token of love and friendship more than I shall dare to express here.”

I won’t keep you in suspense: as far as I can tell, Phinney and the young lady in question never saw each other again. But she wrote to him six months later, prompting him to reflect, in the only other entry he wrote about her: “Who would imagine that she would remember me enough to write such a letter after such a time since we met has elapsed. I am sure I didn’t when we enjoyed ourselves so pleasantly on the Eastern Shore of ‘Maryland, My Maryland,’ – as she used to sing so sweetly.” But she lived too far away, and he was a “wandering vagabond” and “scallawag” who couldn’t provide for a family. So he concluded: “I guess it will be best policy to let them all slide Nettie, Emma, and Lizzie, the whole boodle of them.”

Phinney didn’t let the whole boodle slide, however, at least not permanently. He married in 1869 to Susan Jane Turner, with whom he had two children before she died 13 years later. Phinney then married Priscilla Chase Morris and had four more children.

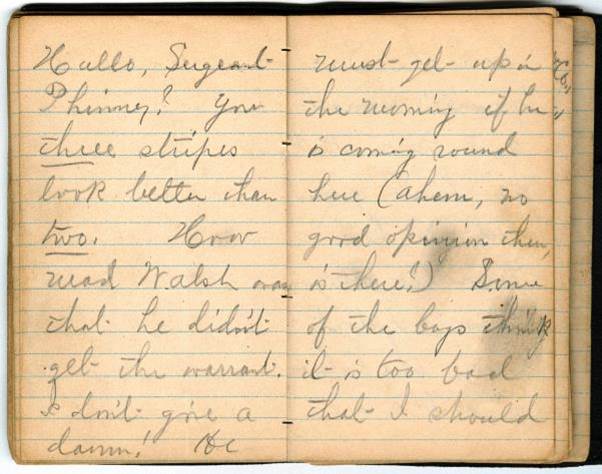

Other entries in Phinney’s diary are interesting, funny, or just plain cryptic. He had a tendency to scribble down random thoughts, financial memoranda, aphorisms, etc. He also sometimes vented his frustration. After his promotion to sergeant of the guard, he wrote: “Hullo, Sergeant Phinney? Your three stripes look better than two. How mad Walsh was that he didn’t get the warrant. I don’t give a damn!”

And here’s an excerpt from his description of the day Abraham Lincoln died, which stretches for several pages: “This has been a day of sorrow and mourning for the nation. […] On the opening of the telegraph office there was an immense crowd gathered in front of the entrance, awaiting, with intense anxiety, something definite in regard to the matter. Alas! The news was too true, for the wire confirmed what we had before hesi[ta]ted to believe. We cannot depict the horror and grief that seized our community.”

The MHS also holds a copy of Catch ’ems?, a beautiful two-volume compilation of the letters of Phinney’s daughter Ellis Phinney Taylor, published in 2004 by other members of the family. Although the letters date from the early 20th century, Catch ’ems? gave me my first glimpse of Joseph Warren Phinney and the Phinney family.

Phinney was born in 1845, the only son and youngest child of Warren and Henrietta J. (Smith) Phinney. His mother died just a few months after his birth, and his father a few years later, so young Phinney was raised by his maternal grandparents. After the Civil War, he became a printer and type founder and designed several typefaces. He died in 1934 at the age of 89.