By Susan Martin, Collections Services

I’d like to take this opportunity to write about the topic that’s been dominating U.S. headlines and occupies countless hours of on-air and on-line punditry: the annual migration of the monarch butterfly.

Just kidding. Yes, I mean the U.S. presidential election. Bear with me.

Historical perspective is our bread and butter here at the MHS, of course. Studying the past is almost always both illuminating and sobering. So I thought I’d revisit the U.S. presidential election of 1788-1789, when 56-year-old George Washington became the first chief executive of the brand-new nation.

Looking for inspiration, I browsed through our collection of Miscellaneous Manuscripts, what we call an “artificial” collection. These documents were donated to the MHS at different times, and each is cataloged individually in our online catalog. They’re arranged chronologically, so I could zero in on a specific date range.

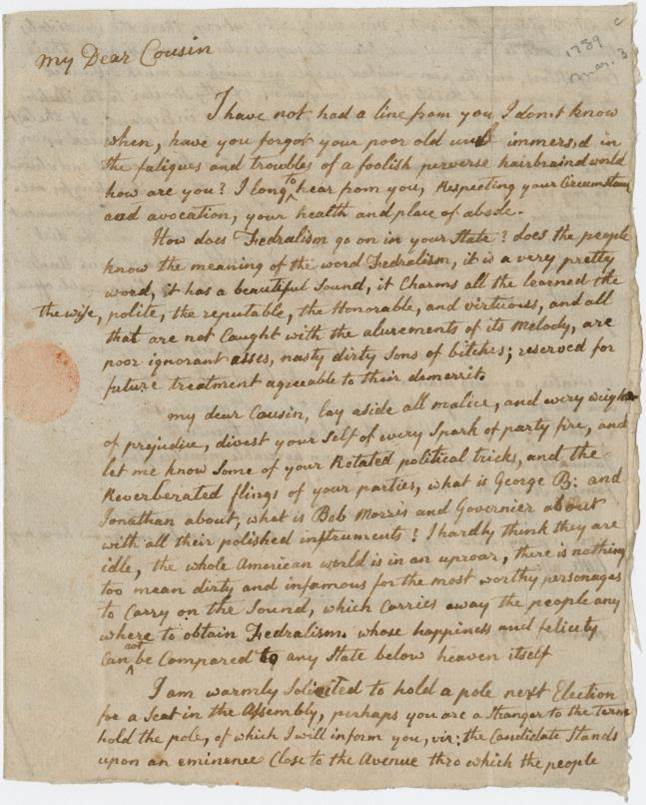

I came across a document I’d never seen before but loved immediately. It’s a letter from Baptist minister David Thomas (1732-1815) in Virginia to his nephew Griffith Evans (1760-1845) in Philadelphia. The letter is dated 3 March 1789. After complaining that he’d been “immers’d in the fatigues and troubles of a foolish perverse hairbraind world,” Thomas launched into a bitter diatribe about the sweeping Federalist victory in the presidential election two months before. His letter is dripping with sarcasm and contempt:

“How does Fedralism go on in your State? Does the people know the meaning of the word Fedralism, it is a very pretty word, it has a beautiful sound, it Charms all the learned the wise, the polite, the reputable, the Honorable, and virtuous, and all that are not Caught with the alurements of its melody, are poor ignorant asses, nasty dirty sons of bitches; reserved for future treatment agreeable to their demerrit. […] The whole American world is in an uproar.”

It’s hard to imagine the kind of sea change Thomas was living through. In fact, this letter was written just one day before the U.S. Constitution went into effect, superseding the Articles of Confederation. Thomas clearly resented the strong centralized government that was set to replace the looser confederation of independent states that he preferred.

George Washington belonged to no political party and was elected unanimously, a circumstance inconceivable today. But far from inconceivable is Thomas’s frustration at his state’s convoluted electoral process, which he described in detail:

“Perhaps you are a Stranger to the term hold the pole, of which I will inform you, viz: the Candidate stands upon an eminence close to the Avenue thro which the people pass to give in their votes, viva voce, or by outcry, there the candidates stand ready to beg, pray, and solicit the peoples votes in opposition to their Competitors, and the poor wretched people are much are much difficulted by the prayers and threats of those Competitors, exactly Similar to the Election of the Corrupt and infamous House of Commons in England.”

He’d narrowly escaped a seat in the Virginia Assembly himself:

“At the last Election I was drag’d from my Lodging when at dinner, and forced upon the Eminence purely against my will, but I soon disappeared and return’d to my repast, and as soon as they lost sight of me they quit voting for me. Such is the pitifull and lowliv’d manner all the Elected officers of Government come into posts of honour and profit in Virginia, by Stooping into the dirt that they may ride the poor people; and would you have your Uncle to divest himself of every principle of honour to obtain a disagreeable office[?] I hope not.”

So, if you get fed up with political shenanigans, chicanery, and tomfoolery this election season, what Thomas called “Rotated […] tricks” and “Reverberated flings,” remember that you’re not alone. And be sure to visit the MHS library to learn more about early American politics—or butterflies, if you prefer.