By Susan Martin, Collection Services

What is the best way to remember our wars? What kinds of public commemorations are appropriate after peace has been achieved? What effect do such commemorations have on our relations with allies who were once our enemies? These were questions that concerned Noah Worcester (1758-1837), Revolutionary War veteran, Unitarian minister, and one of the founders of the Massachusetts Peace Society.

In early 1825, when Worcester heard that newly elected U.S. Rep. Edward Everett would be delivering an address on the fiftieth anniversary of the battles of Lexington and Concord, he decided to reach out. Of course, 1825 was not only a Revolutionary War anniversary year; it was also just ten years out from America’s more recent war with England.

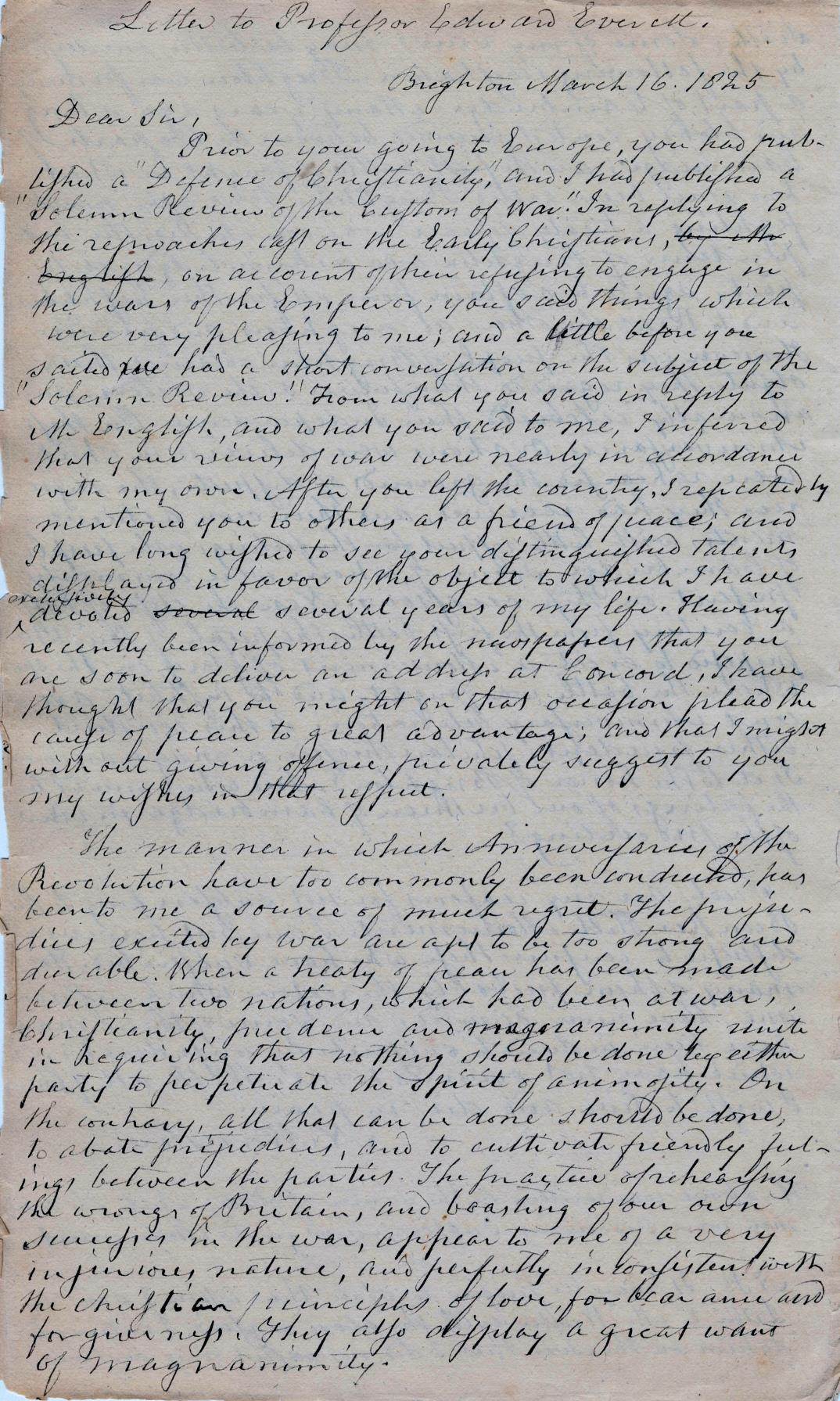

A draft of Worcester’s 16 March 1825 letter to Everett was recently acquired by the MHS. It reads, in part: “The manner in which Anniversaries of the Revolution have too commonly been conducted, has been to me a source of much regret. The prejudices excited by war are apt to be too strong and durable. When a treaty of peace has been made between two nations, which had been at war, Christianity, prudence and magnanimity unite in requiring that nothing should be done by either party to perpetuate the spirit of animosity. On the contrary, all that can be done should be done, to abate prejudices, and to cultivate friendly feelings between the parties. The practice of rehearsing the wrongs of Britain, and boasting of our own successes in the war, appear to me of a very injurious nature, and perfectly inconsistent with the Christian principles of love, forbearance and forgiveness.”

Most Americans undoubtedly celebrated these Revolutionary anniversaries with patriotic pride, but Worcester was disturbed by their emphasis on triumphalism over reconciliation. While he “sincerely rejoice[d]” in America’s victory, he felt that blame for the conflict “was not all on one side” and that the colonists “had less cause of complaint than we imagined” at the time. He warned against rehashing old resentments and encouraged Everett to promote “a new and pacific character to our Anniversaries of the Revolution,” even quoting some of Everett’s own pacifistic words back to him.

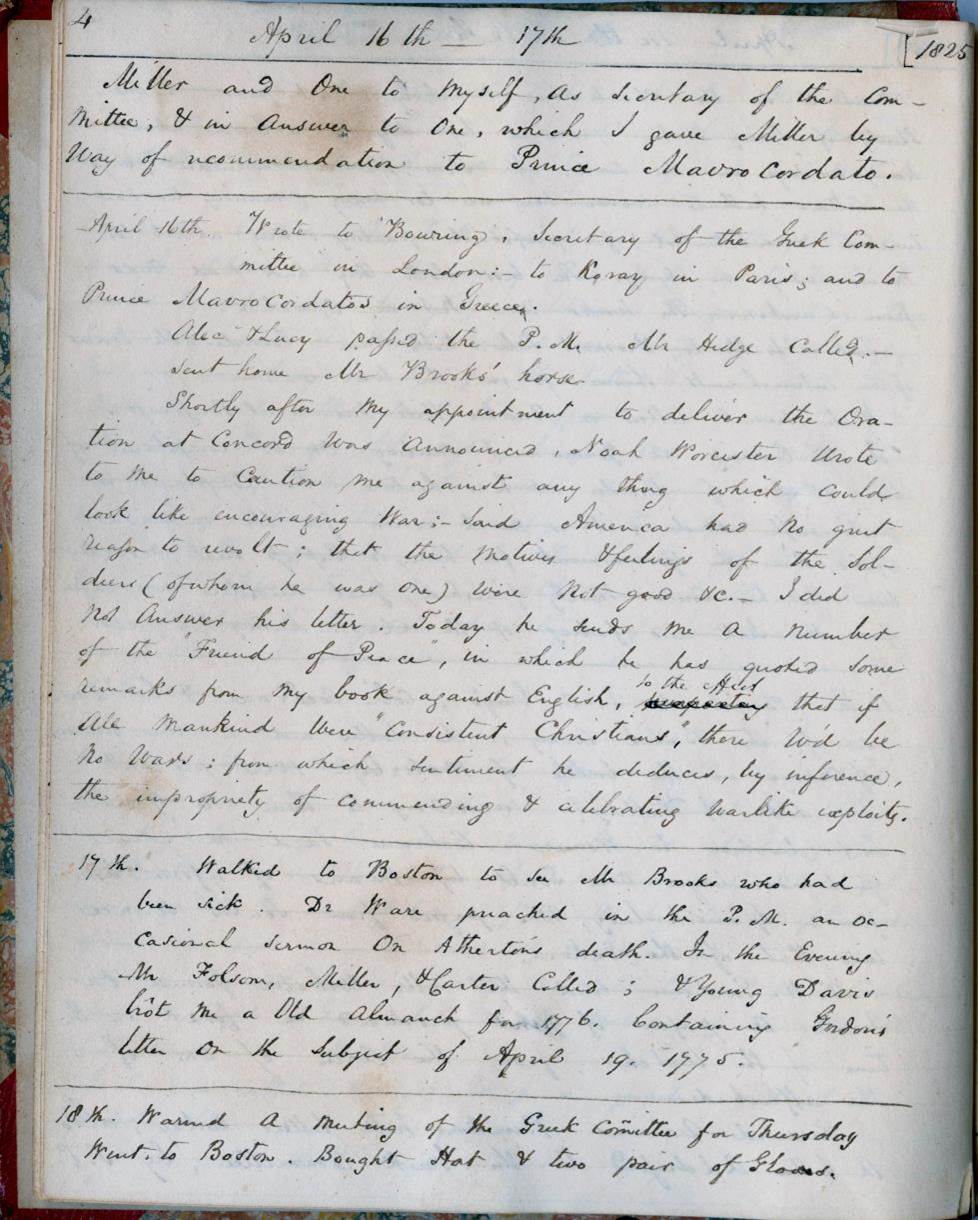

Worcester’s letter definitely made an impression. In his diary, Everett wrote with some contempt: “Shortly after my appointment to deliver the Oration at Concord was announced, Noah Worcester wrote to me to caution me against any thing which could look like encouraging War; said America had no great reason to revolt; that the motives & feelings of the Soldiers (of whom he was one) were not good &c. I did not answer his letter. Today he sends me a number of the ‘Friend of Peace,’ in which he has quoted some remarks from my book[…]; from which sentiment he deduces, by inference, the impropriety of commending & celebrating warlike exploits.”

And Everett’s Concord address was scathing. While he did not name Worcester publicly, he devoted several paragraphs to rebutting Worcester’s arguments in tones of muscular nationalism: “There are those, who object to such a celebration as this, as tending to keep up or to awaken a hostile sentiment toward England. But I do not feel the force of this scruple. […] A pacific and friendly feeling towards England is the duty of this nation; but it is not our only duty, it is not our first duty. America owes an earlier and a higher duty to the great and good men, who caused her to be a nation. […] I am not willing to give up to the ploughshare the soil wet with our fathers’ blood; no! not even to plant the olive of peace in the furrow.”

Everett called “abject” any person who would “think that national courtesy requires them to hush up the tale of the glorious exploits of their fathers and countrymen.” But Worcester hadn’t suggested that we forget the past; he just took issue with the way we remember it. This mischaracterization of his position may have been what Worcester meant when he annotated this draft of his letter: “The above letter was sent to Mr E. soon after its date. The effect it had on his mind, as it appeared in his subsequent oration, was to me a matter of deep regret.”

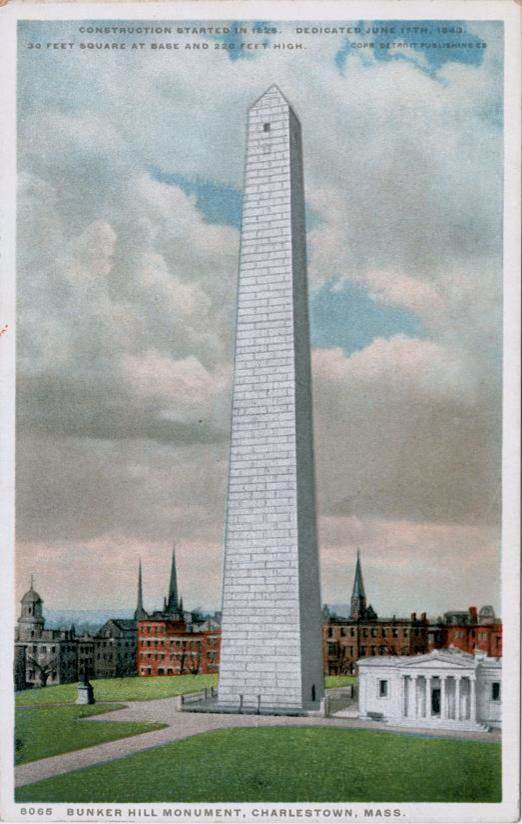

Next Friday is Bunker Hill Day here in Massachusetts. On 17 June 1825, a ceremony was held in Charlestown, Mass. and the cornerstone laid for the Bunker Hill Monument. Worcester, who had fought in the battle as a teenager exactly fifty years before, did not attend the dedication ceremony and declined to subscribe to the monument. Instead, he wrote a poem called “Solitary Commemoration.” Here’s an excerpt:

In every conflict of the martial kind,

Each party thinks he sees the other blind;

But neither sees how hatred on his part,

Deforms the soul while rankling in the heart.

Hatred to whom he knows not, but to those

Who chance to bear the general name – his foes.

Alas! tho’ fifty years have passed away,

Since on that Hill was seen the bloody fray –

On that same ground, lo! myriads celebrate,

Those mournful deeds of horror, death, and hate!

May I, as one preserved in that dread scene,

Ask what these pompous celebrations mean?