By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

That was the line in our online catalog that caught my eye last week. Sandwiched between portrait descriptions and mention of a family crest, this hint about a tintype dating to the 1870s in the Homans family photographs collection was too arresting not to follow up on.

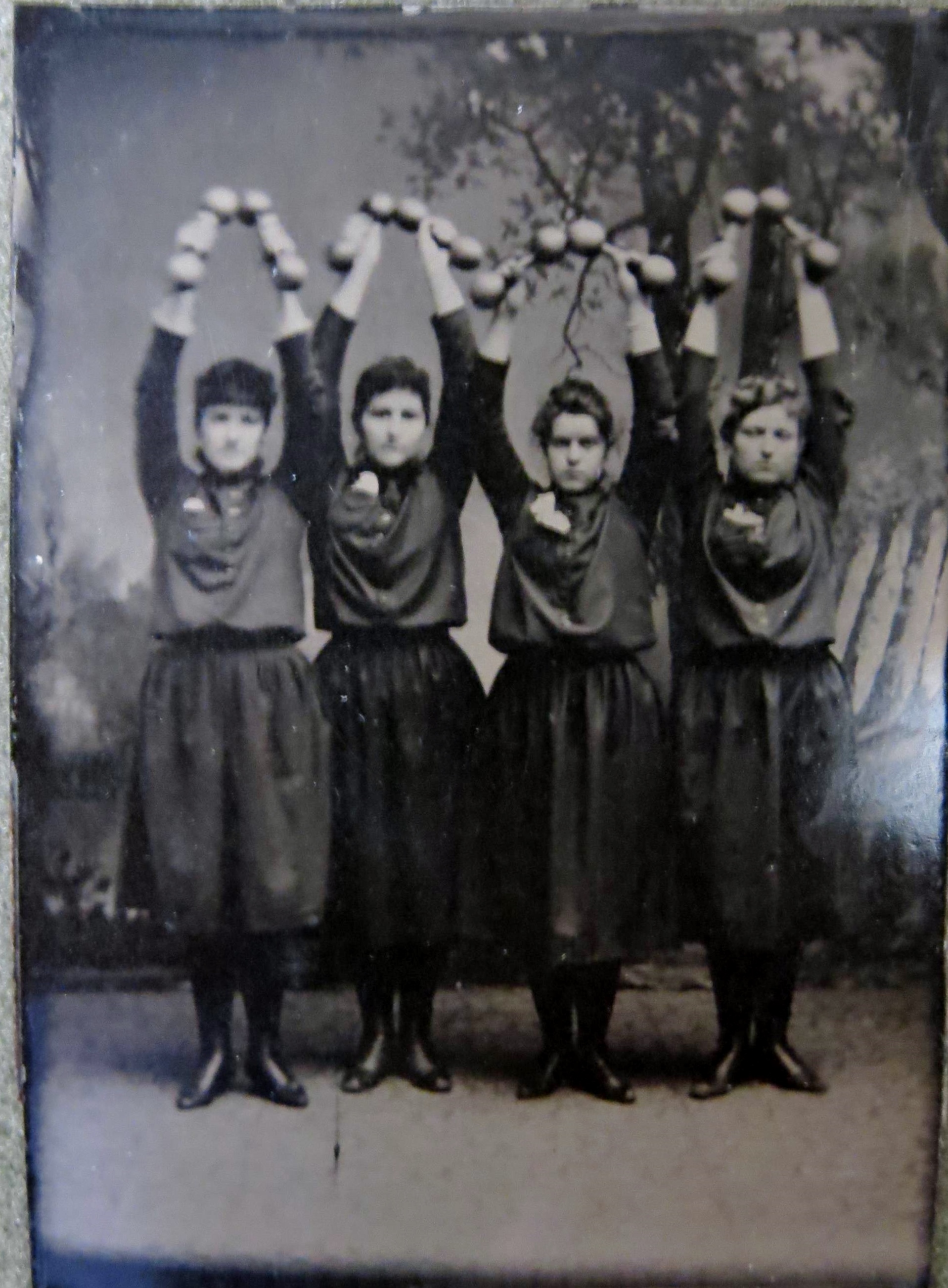

I pulled the appropriate box from our photograph collection and sure enough, the second-to-last folder bore the title “four unidentified girls exercising, ca. 1870-1880. Photographer unknown. Tintype.” Four girls exercising? My interest was well and truly piqued.

Tintype of four girls lifting dumbbells, ca. 1870-1880. Found in the Homans family photographs.

Facing the camera, the four girls wear matching outfits, complete with white handkerchiefs tucked into their chest pockets and shiny black shoes. They appear to be in their mid-to-late teens and are standing straight-spined, each holding aloft two dumbbells.

In a collection of unremarkable individual and group portraits, this photograph raised a multitude of questions for me, chief among them being, why are these girls lifting weights? What group are these girls a part of that they are identically dressed and posing for this photograph? Was this common practice for Boston-area women in the 1870s? While common practice today, weight-lifting women were not always so familiar.

I took a two-pronged approach to answering these questions, first searching the Homans family papers, including the 1878 and 1881 diary of teenager Mattie Homans, to see if I could find reference to this type of exercise, and then looking at our collections more broadly for materials related to women’s gymnasiums in Boston and physical education for women.

The Homans family papers disappointingly failed to illuminate the context for this photograph, and so I moved on to other, related resources.

Ideas regarding health, fitness, and the role of physical activity for shaping personal and cultural character changed dramatically over the course of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, and this photograph illuminates the pervasiveness of these changes. Puritan beliefs that illness was an unavoidable and even expected aspect of their daily lives, gave way to the active promotion of health and hygiene through personal actions and environmental changes. 19th century Boston played host to a multitude of facilities, practitioners, and publications devoted to shaping the public discourse on physiology and hygiene, and middle class citizens, particularly women, were at the heart of this movement.

In Able-Bodied Womanhood: Personal Health and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century Boston, Martha H. Verbrugge posits that

“[A]ntebellum health reform prescribed self-governance to alleviate the problems of urban life. The world seemed unmanageable to Boston’s middle class . . . [i]n an unpredictable and seemingly uncontrollable world, [they] looked inward for stability. Self-control appeared to be the most reliable, perhaps only, mechanism for restoring order.” (47)

While Bostonians believed that a person’s biological characteristics (like a weak heart), and their physical environment (like a drafty house) contributed to their health, or lack-thereof, they placed the greatest emphasis on the role of personal behavior in actively shaping their lives.

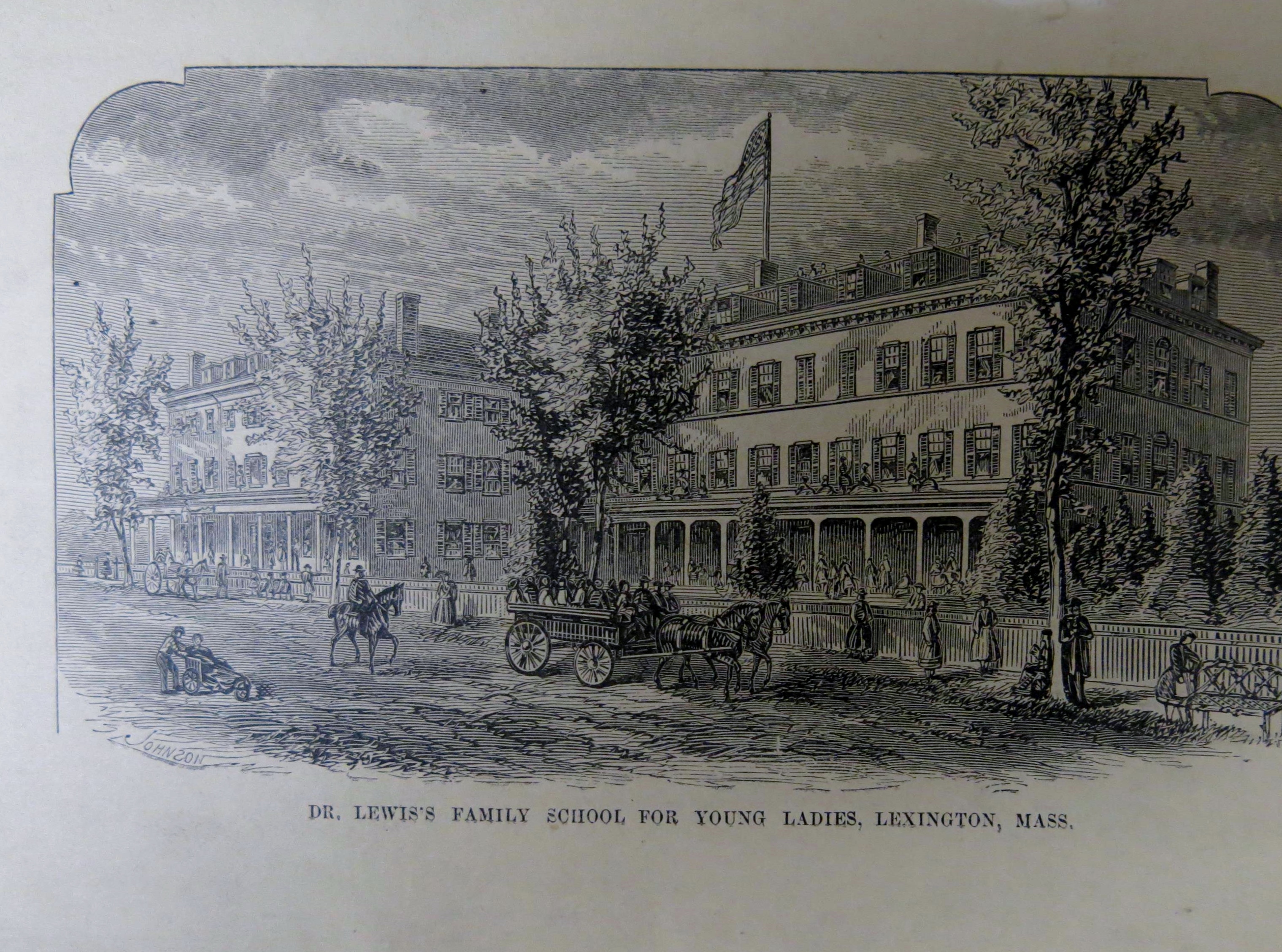

Attempting to break the monopoly men held over early gymnasiums, Bostonians such as Dr. Dio Lewis and Mary E. Allen, opened gymnasiums catering specifically to women and children. In 1860 Lewis opened the New Gymnasium, focused almost exclusively on promoting muscular development in children of both sexes, and his Family School for Young Ladies in Lexington, MA, which centered its curriculum around both intellectual and physical instruction.

Dr. Lewis’s Family School for Young Ladies. Sketch found in “Catalogue and circular of Dr. Dio Lewis’s Family School for Young Ladies, Lexington, Mass. 1866.”

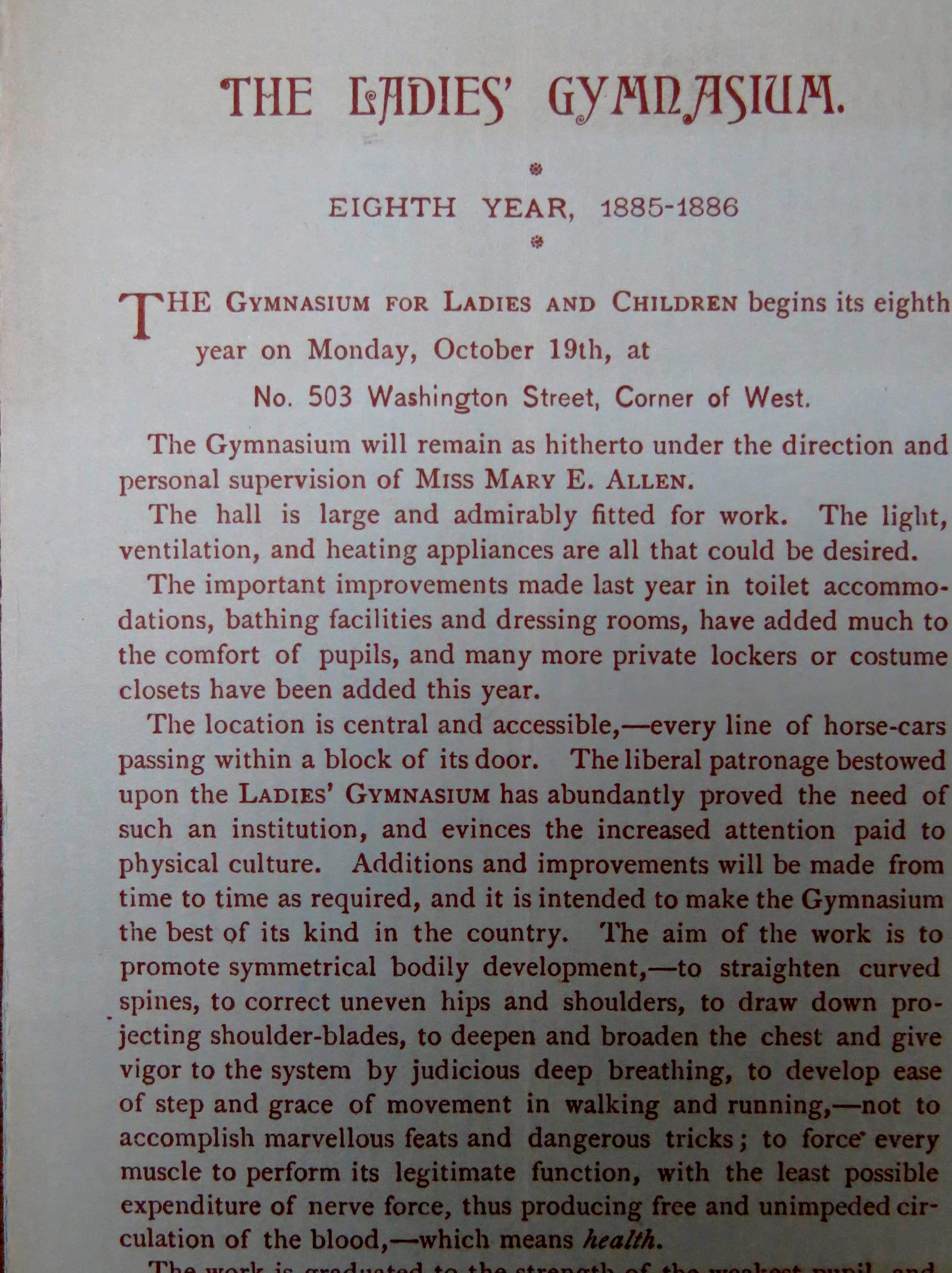

Mary E. Allen continued this trend into the 1870s, opening the Ladies Gymnasium on Washington St. in 1877 and offering facilities for women and children to conduct slow, careful, and progressively more difficult physical exercise in the pursuit of “symmetrical bodily development”. In addition to providing a gymnasium, Allen also taught a so-called “Normal Class . . . for the instruction of those who intend to teach Gymnastics, either in public or private schools, or in Gymnasiums devoted to women and children, an urgent need of which exists in the larger towns and cities.” Not only training women to improve their own physiques, but to become teachers of such methods themselves.

“The Ladies’ Gymnasium. Eighth Year, 1885-1886”

This broadening emphasis on physical culture was deeply intertwined with changes in beauty and fashion standards, the roles of middle class women in the private and public spheres, and developments in science and medicine. Verbrugge’s work does a wonderful job of addressing the intersectionality of these varied forces, particularly within the sphere of Boston society.

Taking these sources in concert, it is no longer strange to have found the image of young women lifting dumbbells, particularly within the family photograph collection of a prominent Boston family. Unfortunately, I was not able to identify the women in the photograph, or establish their affiliation with a particular school or gymnasium. That will have to be a project for another day.

If 19th century dumbbells strike your fancy and you would like to see the Homans tintype in person, please feel free to stop in and visit our library. If you are interested in seeing what other materials we have related to physical education, you can browse our online catalog, ABIGAIL from the comfort of your own home.