By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

[If you have trouble seeing the small details in some of these images, hold Ctrl and press + to zoom in on your browser.]

Whether as an educational tool, a creative form of political commentary, or a crafty way of targeting a chosen audience, rebuses have been used for centuries. Dating back to 1540 and the work of calligrapher and engraver Palatino, rebuses harness text, numbers, and images of recognizable objects as phonograms and hieroglyphics to convey meaning. I tracked down four examples from the MHS collections, and was surprised by the difficulty and intricacies of their presentations.

Rebuses rely on two primary usages for images: either as hieroglyphics or phonograms. Using hieroglyphics, authors can convey straightforward words by simply replacing them with an image that shows their meaning, such as ![]() replacing the word “ship”. To express more abstract words, creators juxtapose letters and drawings that could be used as phonograms. When combined, these sounds build words, such as

replacing the word “ship”. To express more abstract words, creators juxtapose letters and drawings that could be used as phonograms. When combined, these sounds build words, such as ![]()

![]() representing the word “cannot”. In linguistics this is actually called the “rebus principle”.

representing the word “cannot”. In linguistics this is actually called the “rebus principle”.

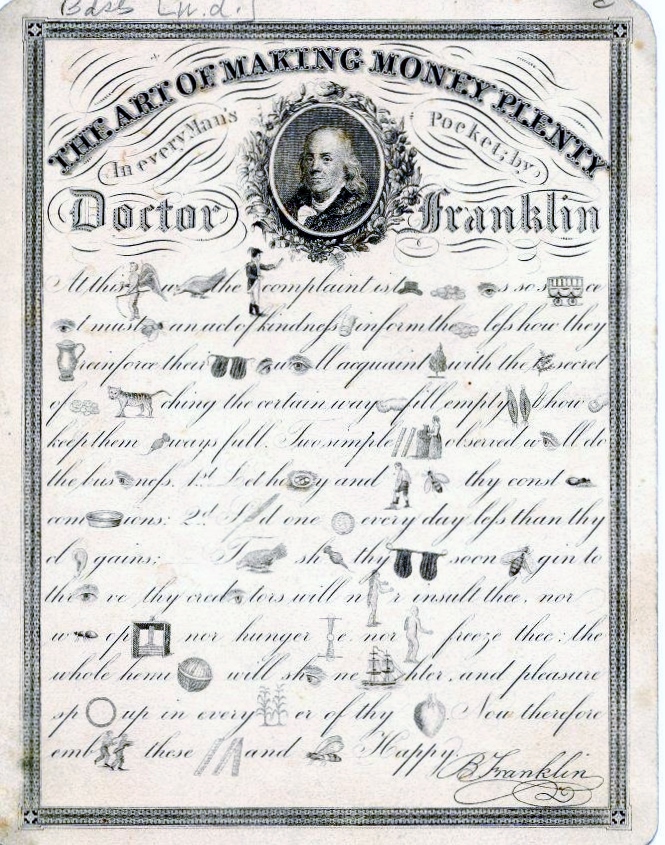

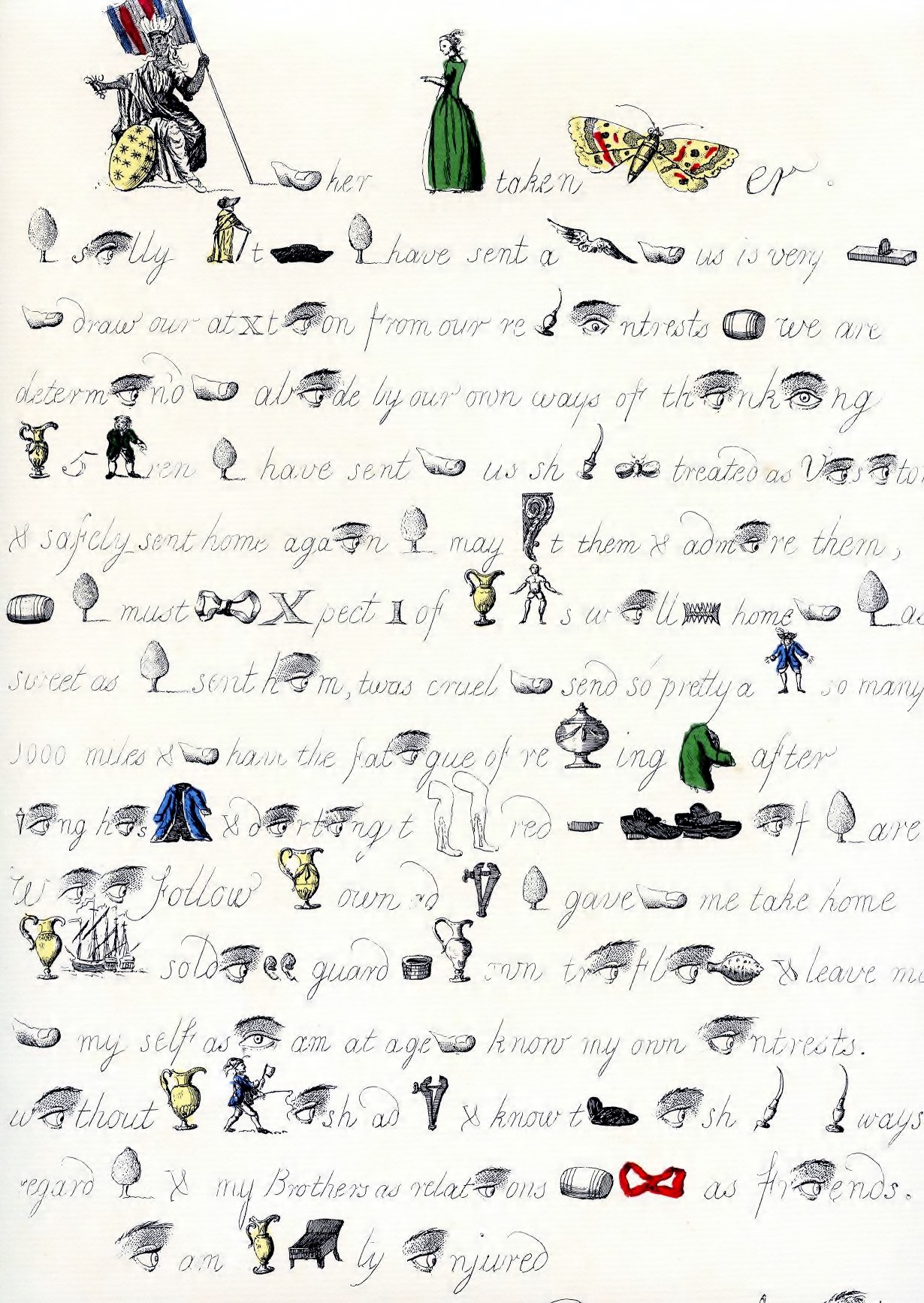

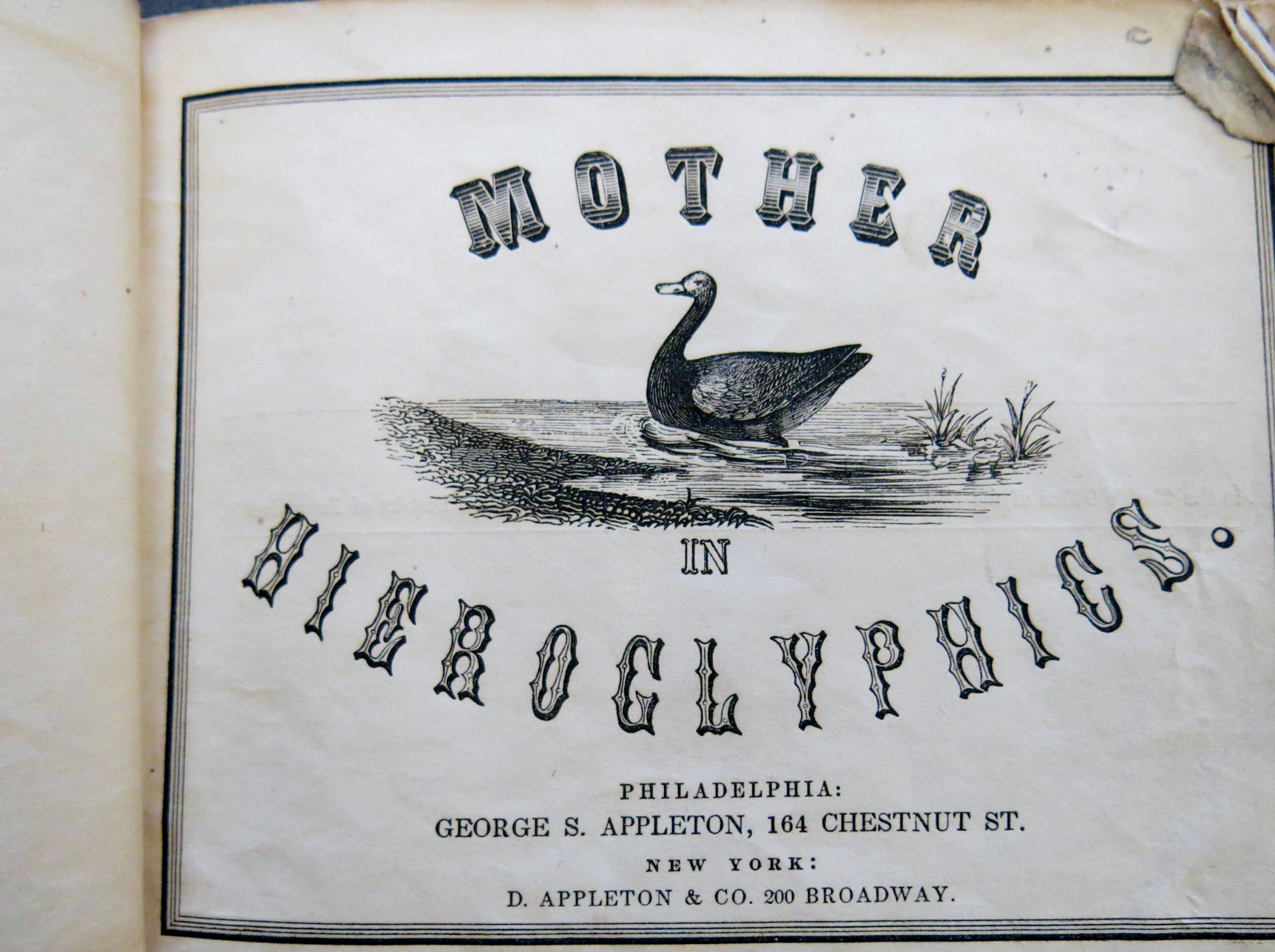

Both techniques can be seen in Benjamin Franklin’s “The Art of Making Money Plenty in every Man’s Pocket” (circa 1848), Matthew Darly’s satirical publications from the American Revolution entitled “Britannia to America” and “America to her mistaken mother” (both published in London in 1778), and an unattributed educational publication of Mother Goose in Hieroglyphics (1849).

“The Art of Making Money Plenty in every Man’s Pocket”

As I worked my way through these puzzles I began to recognize a specific vocabulary of images, a vocabulary that I was surprised to discover took some serious investigation to fully understand. Even with full-text translations to reference it took the help of several colleagues to track down the names for all of the images pictured.

“Britannia to America”

“America to her mistaken mother”

Rebuses speak specifically to the historical context in which they were created. They rely on commonly understood imagery to convey meaning, and as I compared the rebuses I was able to construct a set of common images, always used identically. Because the content of the individual excerpts is different: Franklin’s lectures on personal fiscal responsibility, Darly’s speak to the British fear of a strategic partnership between the colonists and France, and Mother Goose telling a children’s fairytale, the overlap is limited, but that which does exist exemplifies a historical context that makes its interpretation by 21st century minds difficult.

Some common sounds represented identically across these publications include

(eye) = “i”

(eye) = “i” (an individual toe) = “to”

(an individual toe) = “to” (yew tree) = “u” (“you”)

(yew tree) = “u” (“you”) (awl) = “all”

(awl) = “all” (bee) = “be” or “b”

(bee) = “be” or “b” (ewer) = your

(ewer) = your

While some of these images are easily recognizable even today (the bee, or a human eye), others are no longer commonplace in most of our lives, such as an awl, or a ewer.

Changes over time in storage, weight, and measurements have also disassociated other commonly used pictures, such as a cask ![]() , from traditionally related terms like “butt,” a British unit of measure.

, from traditionally related terms like “butt,” a British unit of measure.

Just like Franklin’s and Darly’s works, Mother Goose uses the ewer, awl, toe, and butt images to convey a story, but unlike the others Mother Goose includes an introductory note as to the importance of the use of images within the text itself. The unknown author of the Mother Goose rebus introduces the work with the words “When the doctor sends for physic for a nervous little chick, make a mistake, and go to the bookseller’s and buy Mother goose in Hieroglyphics; that’s what is wanted — a pretty book, written with pictures, as they wrote in Egypt a long while ago, when folks new something.” While Franklin uses the rebus structure to make sure readers are challenged to expend effort before obtaining answers, Mother Goose uses them as a teaching tool, bridging the gap between speech and textual understanding in children.

Mother Goose

To see an example of some unpublished rebuses, check out Susan Martin’s June 17, 2015 blog on Samuel W. Everett. Dating to the mid-19th century, Everett’s illustrations demonstrate that early Americans did not just consume these puzzles in printed form, but produced them for personal entertainment as well. If the rebuses in this ![]()

![]() post strike your fancy, consider visiting our library to view them in person, or to explore any of our other collections in greater depth.

post strike your fancy, consider visiting our library to view them in person, or to explore any of our other collections in greater depth.