By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

The breadth of foreign-language materials in our collections often surprises me; we have English and French language conversation primers written in Italian, proverbs in Hebrew and Latin, and Chinese grammar books written in German. So it should not have surprised me, although it did, to discover several fascinating 19th century broadsides and pamphlets on manual languages hidden within our collections as well.

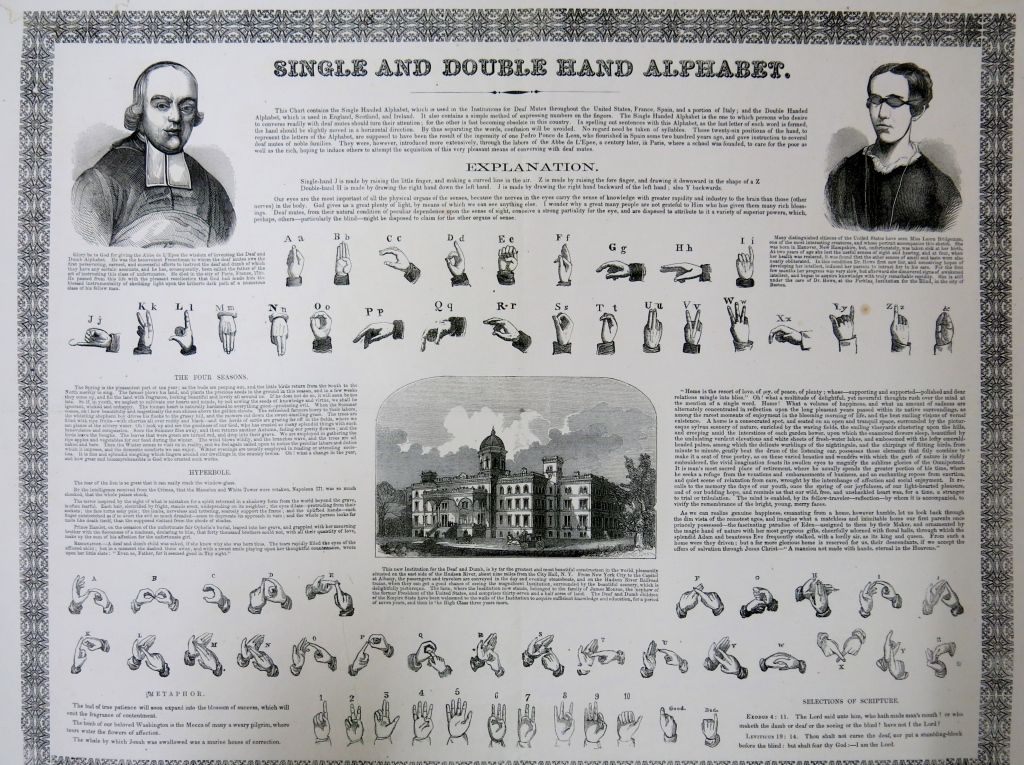

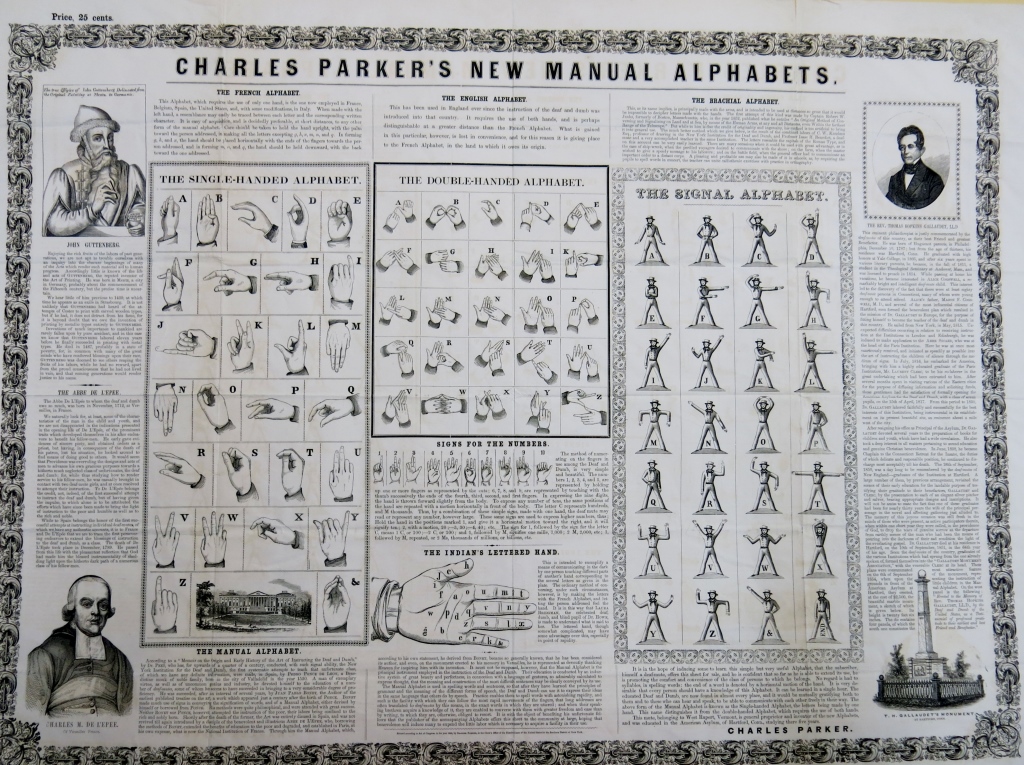

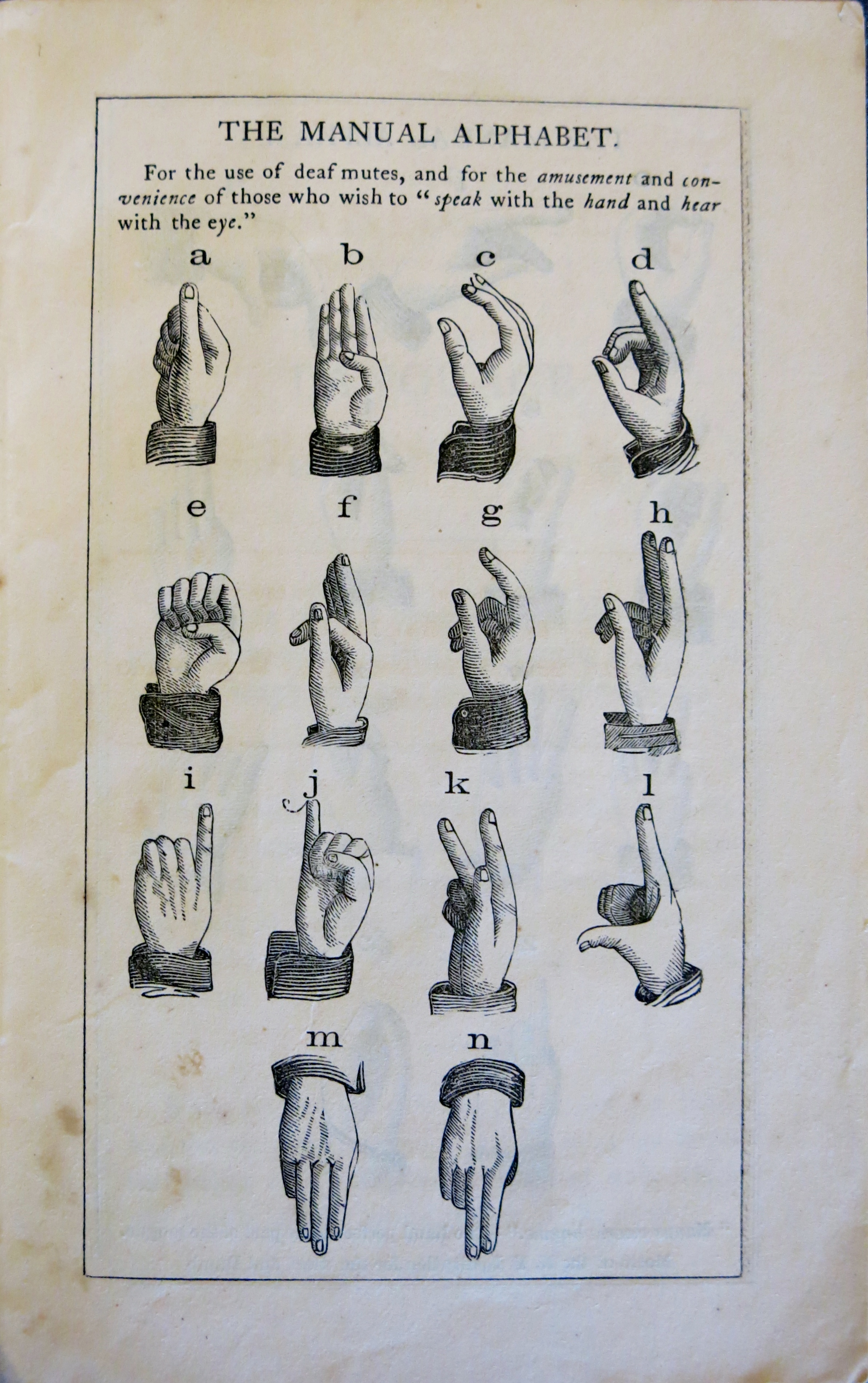

Two broadsides, Single and Double Hand Alphabet (c. 1856) and Charles Parker’s New Manual Alphabets (1856) depict a variety of manual hand and body alphabets, including narrative descriptions of their intended uses, audiences, and histories.

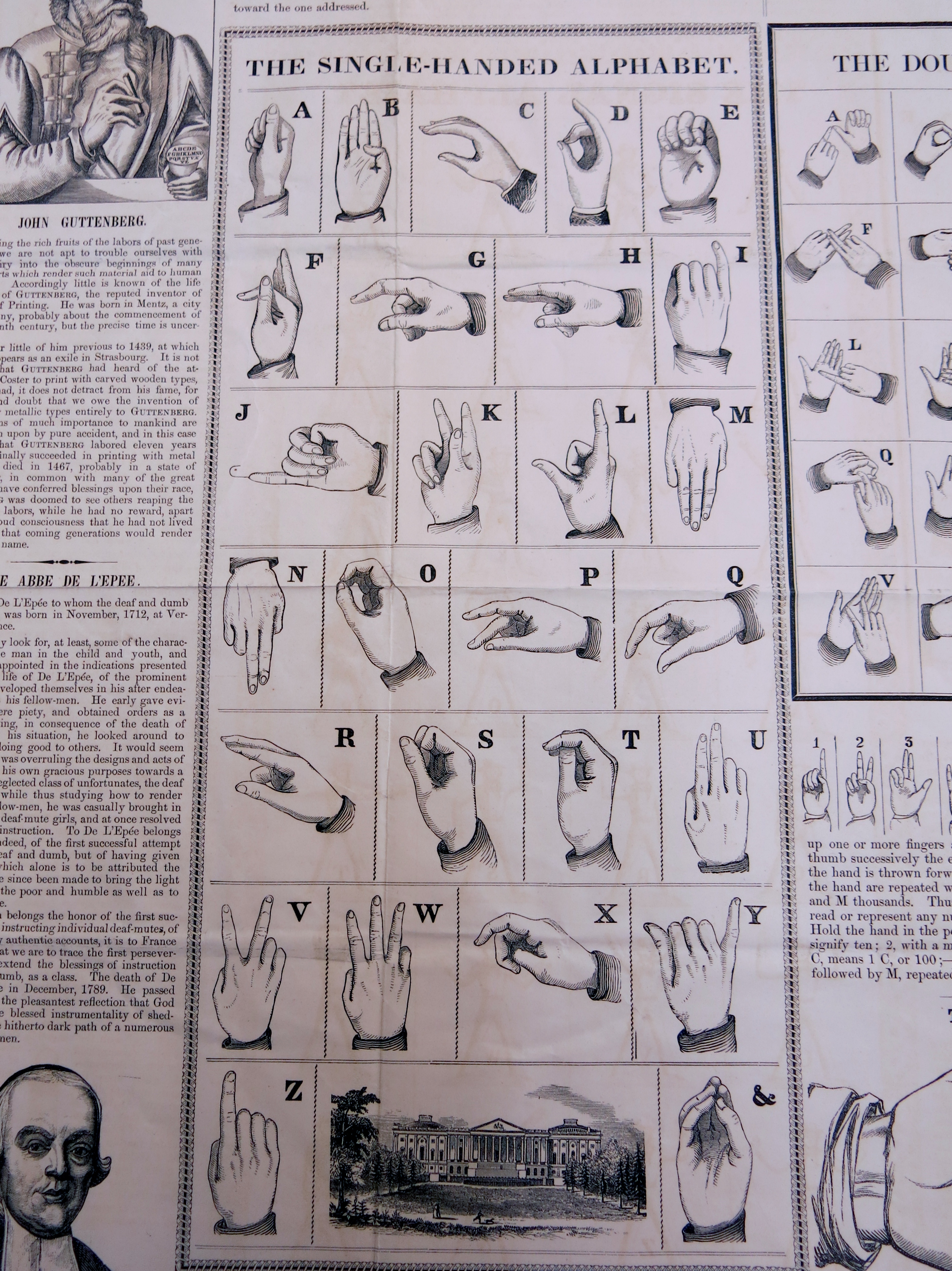

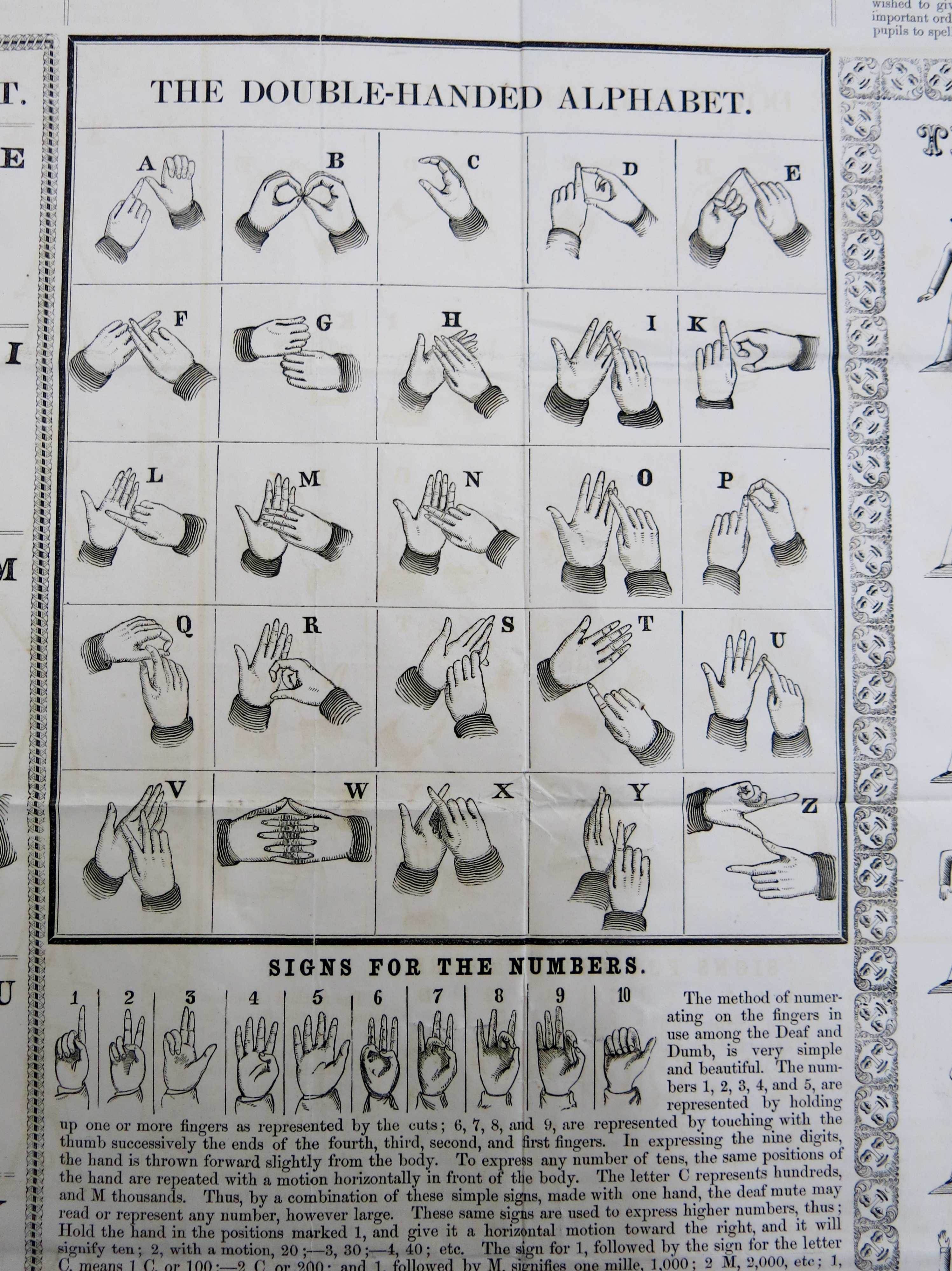

Both items show slight variations on a single-handed alphabet, a double-handed alphabet, and the numbers 1-10.

Single-Handed Alphabet

Double-Handed Alphabet

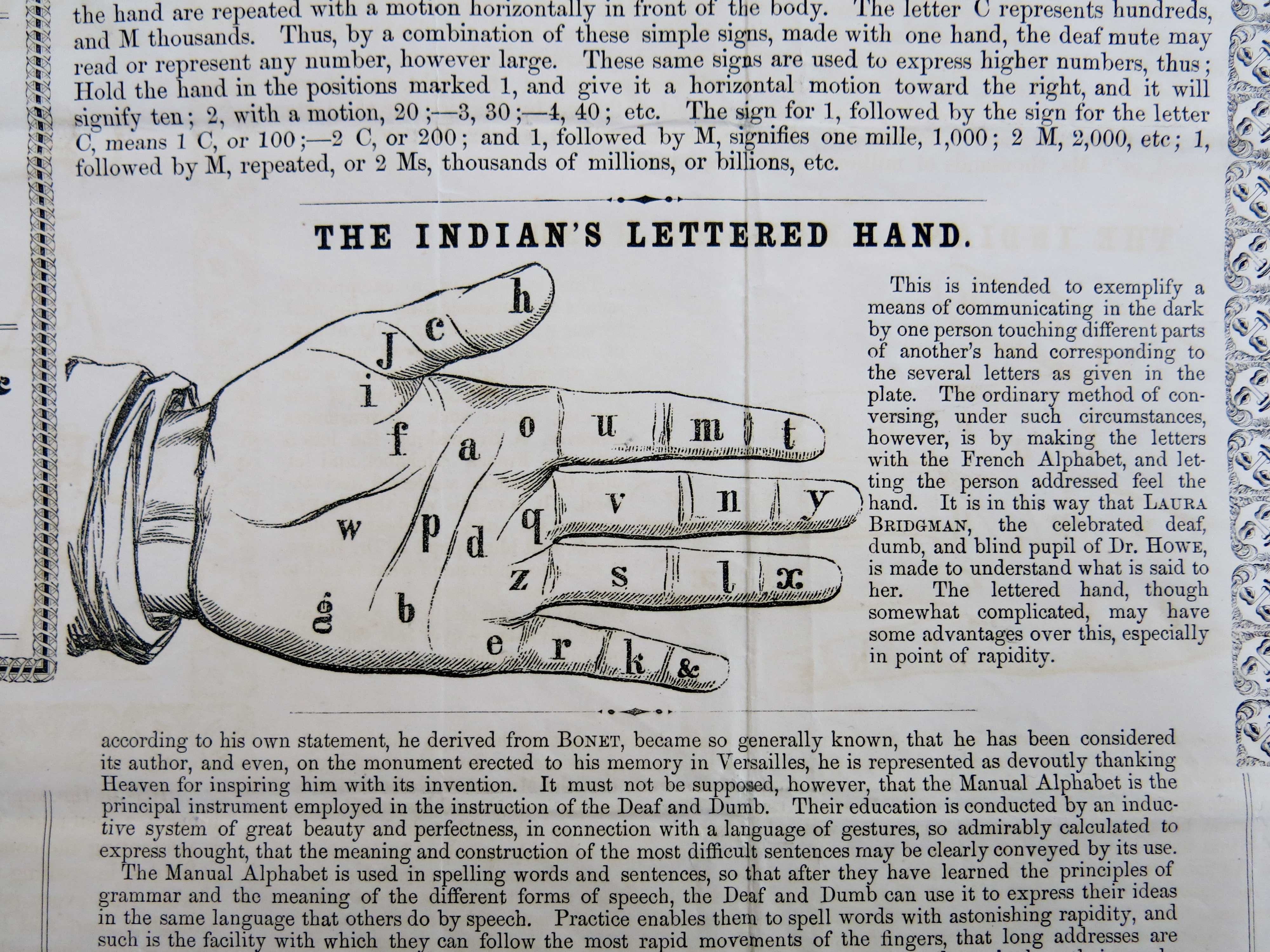

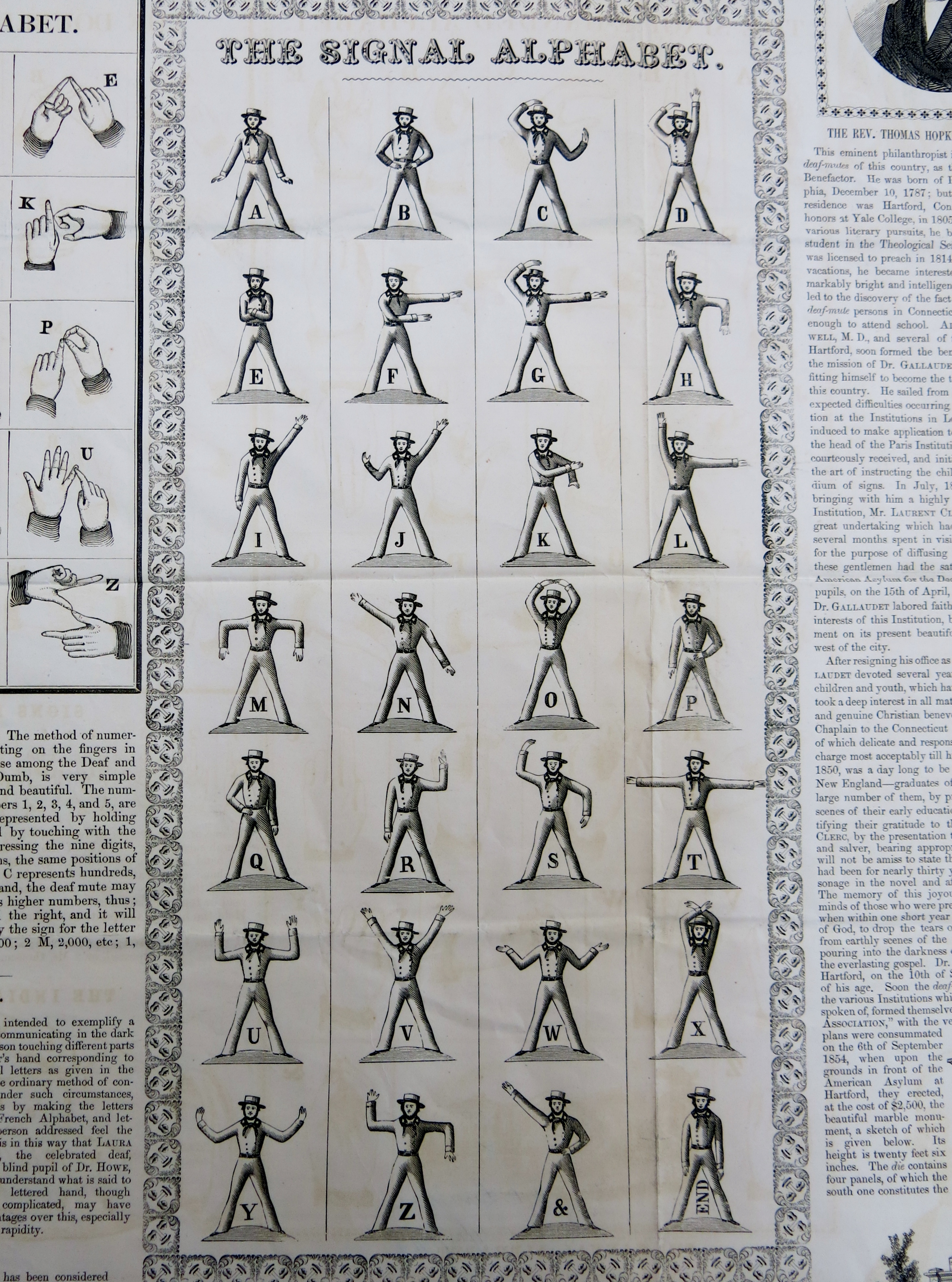

Charles Parker’s New Manual Alphabets also includes “The Indian’s Lettered Hand,” and “The Signal Alphabet.”

The Indian’s Lettered Hand

The signal Alphabet

“The Signal Alphabet” in particular, which looks similar to flag semaphore, caught my eye. Created by C. W. Knudsen Esq. and Professor Isaac H. Benedict, a deaf-mute individual and teacher at the New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, it was derived from a more complex alphabet called the “Brachial Alphabet,” which was published in 1852 by a former Bostonian, Captain Robert Jenks.

“There are many occasions when it could be used with great advantage,” the broadside advertises, “as in the case of ship-wreck . . . on the farm . . . and on the battle field [sic].” I was amused to find these logical implementations followed by the far more outlandish suggestion that “a pleasing and profitable use may also be made of it in schools, as, by requiring the pupils to spell words in concert, the teacher can unite callisthenic [sic] exercises with practice in orthography.”

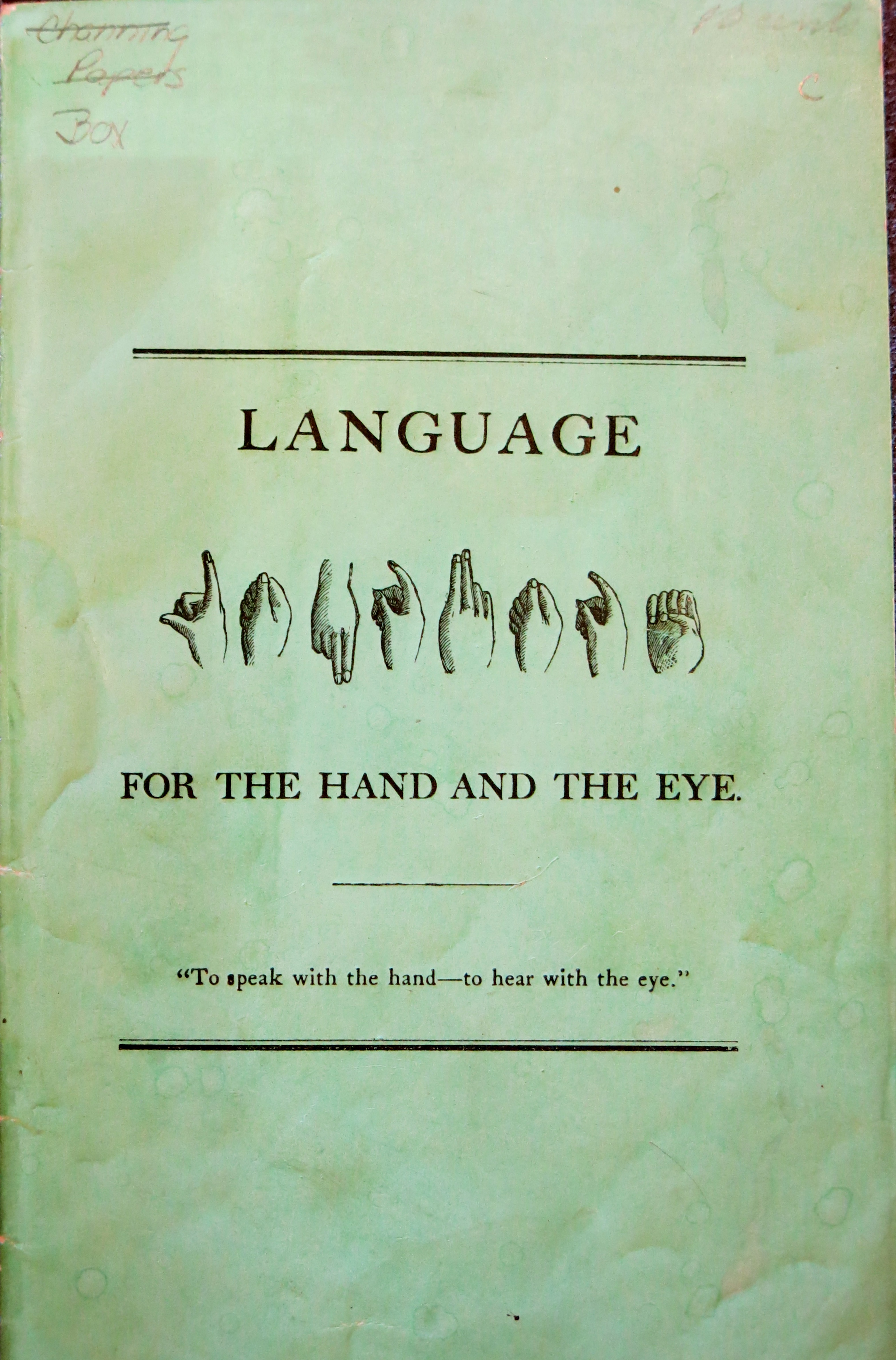

A pamphlet, entitled Language for the Hand and the Eye and dating to a decade after the broadsides, proposes similar benefits for hearing students.

It was a favorite idea of Dr. Gallaudet (the pioneer in the work of deaf mute education in this country,) that the use of the manual alphabet by hearing and speaking children, would prove highly advantageous, by leading their attention to the written form of words, thus aiding them greatly in forming the habit of spelling correctly.

The use of this alphabet is also a pleasant diversion to children. It is an entertainment to them to find that they can produce language in a new form. (7)

The audience for this particular pamphlet is clearly a hearing one. In the postscript of the text, the author, who is unnamed, addresses the reader directly:

Kind reader: — Is there among your acquaintances a little one who has not the power of hearing and speaking — a deaf mute child, unable to acquire this wonderful, beautiful power of language that we all acquire so readily by the ear? If you know of such an one, will you not try to aid the child by teaching it this alphabet, or by inducing the parents, or brothers and sisters, or friends of the little deaf mute to teach it early to use this form of language, and thus save it from unneccessary [sic] ignorance? (10)

The author’s final proclamation makes clear one of the most intriguing aspects of these sources: while they were distributed to propagate a language originally created by the Deaf community, they are directed at hearing individuals with the opinions of deaf individuals filtered through their re-telling by hearing doctors and educators, if they are even included at all.

While some acknowledgement is made of the variations in manual languages between regions, there is no mention of the broader range of formal sign languages to represent and communicate concrete and abstract thoughts beyond the creation of letters. Also omitted is any substantive mention of Deaf culture, or the first-hand account of communicating as a deaf individual.

In addition to these items on manual languages, the MHS also holds a variety of manuscript and print materials pertaining to the personal experience of deaf and mute individuals in New England, as well as educators and doctors who worked with, studied, and taught them. Interested researchers are encouraged to stop by during our open hours to view these, or any of our other collections in person.