By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Three weeks ago, I introduced you to John Egbert Jansen and Margaret A. Wisner of Pine Bush, N.Y. Their papers form part of the Hall-Baury-Jansen family papers and include overlapping diaries for the years 1858 and 1859. One of my colleagues here at the MHS asked me what happened to John and Margaret after 1859, so I did a little more digging.

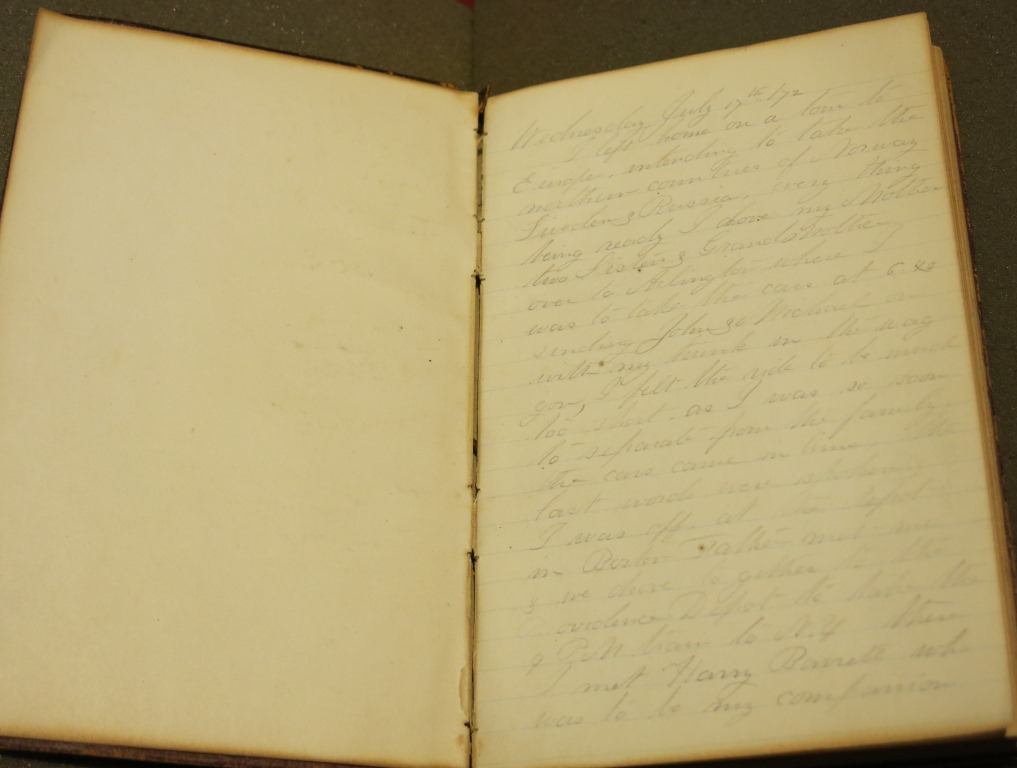

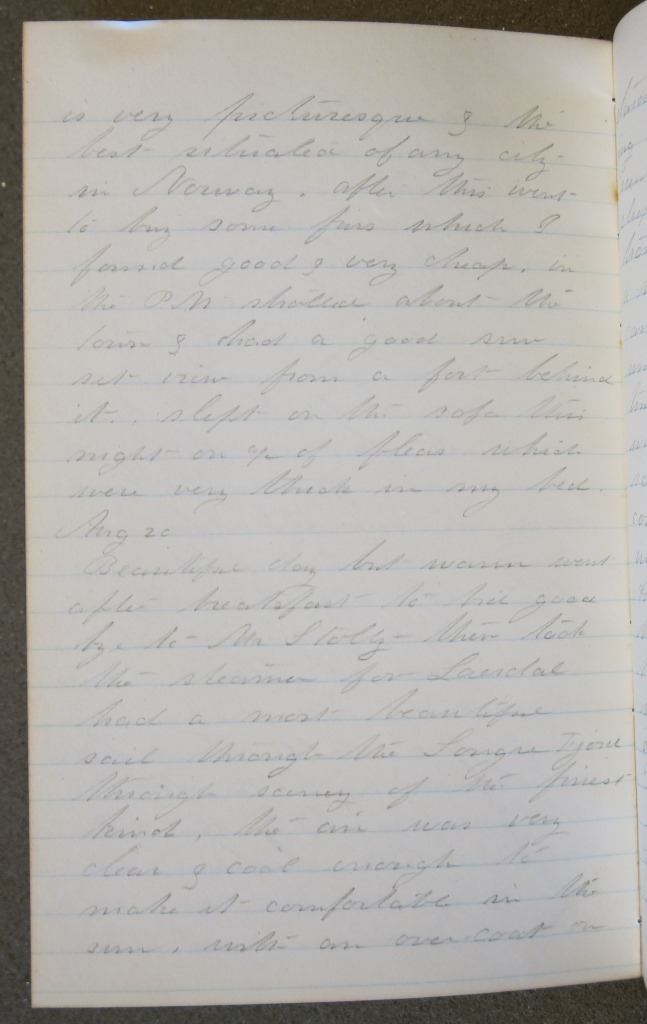

Unfortunately, none of the rest of the diaries in the collection overlap. We have one more diary kept by Margaret in 1862, but the ink has faded so much that many of the entries are illegible. John kept five more diaries, two before his marriage to Margaret (1860, 1861) and three after (1873, 1875, 1878). So we have to rely almost entirely on him for further details.

John’s diary entries are short and cryptic. He visited Margaret and thought of her often, and it seems his feelings were reciprocated, but something was apparently delaying their marriage. The fact that we have only one side of the story heightens the mystery and the pathos. We see John pining for Margaret, “living in hopes,” wanting to say things to her but not daring, and parting from her in “affecting” scenes, but her voice is silent. Here are some excerpts from John’s 1861 diary:

Many wishes I have, but must not express them now, and some inferences to make from former actions. (17 Mar. 1861)

Saw some one in want of sleep as well as myself. I have to think quite little of what I’ve heard lately. (28 Apr. 1861)

The last attempt. […] Not at all afraid. (26 May 1861)

Thinking considerable as to what I must do. (1 July 1861)

Saw one in Church looking sad and lonely. Sorry for that. (24 Nov. 1861)

What the conflict was, I can only guess. There was some discord during John’s visit to the Wisners on 14 Mar. 1861: “Some apparently disappointed in hearing my oppinions of Intemperance as applied to my case.” The day before, he had written: “At home in the evening on account of shame perhaps or the want of a place to go. I dont know what it will amount to. I’ll have to stop after while I guess.” John did take the occasional drink. Did Margaret’s family disapprove? Or was it something else? All we know for sure is that harsh words were spoken, and someone was “very much put out or disgusted.” John felt the sting of “people passing remarks on and about me,” but thought he was “not so bad as I might be.”

His love for Margaret is unmistakable. He referred to her tenderly as “Maggie” and even, in one entry, as his “duckee.” Sometimes he just used a plus (“+”) sign to indicate her, as on 18 Aug. 1861: “Retired early, but could not sleep thinking of the goodness and other qualities of +.” As the year neared its end, with the prospect of their marriage still dim, John was glum: “Dark and gloomy out. Myself dull and lonely. Wonder if any one is thinking of me? Doubts arising.” But on New Year’s Eve, he clung to hope: “As the clock strikes 12 I was happy and alone and may I next New Year’s eve be the same except the alone.”

As I looked through John’s 1861 diary more carefully, I realized that Margaret was not entirely silent after all. At some point, she also read the volume and couldn’t resist adding her own sly comments after some entries. For example, on 7 Oct. 1861, John described an outing with some friends: “Bad companie but hard spoiling me as I am so innocent??” Margaret added a playful: “Poor boy.” (The question marks were also probably written by her.)

We have no diary kept by John in 1862, so we switch to Margaret’s point of view. Her diary for that year, though faded, does contain some legible entries, but their meaning is just as elusive as John’s. The couple had frequent “discussions” and “consultations.” When John visited on 12 Nov. 1862, with nothing decided, the two of them just “sat & sat hoping things would be right.” The wedding was put off at least once, and the next day John was nearly at the end of his rope: “John E. here & to tea. Quite cross when he left. To bad. To bad.”

Finally, on 17 Dec. 1862, John and Margaret were married. Margaret’s entry for that date reads: “Memorable day. Promised much, before many witnesses. Left with My husband […]” John’s later diaries describe the life of a typical New York farm family. The couple had three children: Lewis Wisner Jansen (1864-1925), Elsie (Jansen) Vernooy (1866-1949), and Lt. Col. Thomas Egbert Jansen (1869-1959).

Margaret died in 1923, and John in 1929. They, their three children, and other Jansen and Wisner family members are buried in New Prospect Cemetery in Pine Bush, N.Y.