By Susan Martin, Collection Services

This July 4 marked the 151st anniversary of an interesting political protest by local businessman Joseph Story Fay. His protest provoked heated debate in the Boston newspapers and had professional ramifications for Fay, even months later.

Fay was apparently a Peace Democrat during the Civil War, or what some called a “Copperhead” (as in, the snake). This subset of Democrats supported the Union, but wanted an end to the war through negotiated peace with the Confederacy. At their National Convention in Chicago in Aug. 1864, the Democrats nominated General George B. McClellan to unseat President Lincoln. Their platform read, in part:

[…] after four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war, during which, under the pretense of a military necessity of war-power higher than the Constitution, the Constitution itself has been disregarded in every part, and public liberty and private right alike trodden down, and the material prosperity of the country essentially impaired, justice, humanity, liberty, and the public welfare demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities […]

It’s not hard to imagine what the Republicans thought of that! The Boston Evening Transcript, a pro-Lincoln newspaper, tore into the Copperheads in every issue published that election season. If McClellan won the presidency, the paper editorialized, “compromise and concession to traitors will be the policy of the new administration.” The paper ran stories of rebels cheering McClellan’s nomination and routinely implied that the Copperheads celebrated Confederate victories.

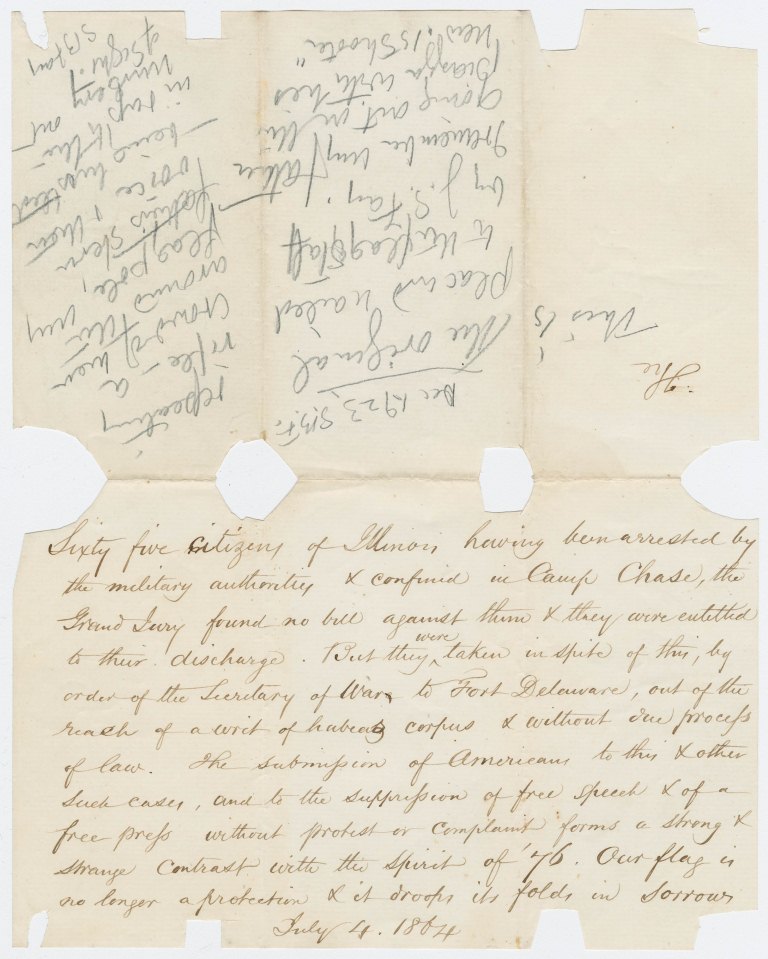

The Peace Democrats argued that the war wasn’t just destructive to the Union, but to the Constitution. They railed against the violations of civil liberties perpetrated by Lincoln’s administration. The spur to Fay’s protest on 4 July 1864 was the suspension of habeas corpus in the case of a group of Illinois Copperheads who had been arrested and detained in a military prison without due process of law. Fay chose Independence Day to make his stand. He flew an American flag at half mast outside his home in Woods Hole, Mass., and attached a note:

The submission of Americans to this & other such cases, and to the suppression of free speech & of a free press without protest or complaint forms a strong & strange contrast with the Spirit of ’76. Our flag is no longer a protection & it droops its folds in sorrow.

There’s some dispute about what exactly happened next, but all accounts agree that a group of people objecting to Fay’s protest confronted him at his house. Fay warned them off, armed with a rifle. His youngest daughter Sarah, about 8 years old at the time, wrote later (her note is visible on the image above): “I remember my father going out on the piazza with his new .15 Shooter repeating rifle – a crowd of men around the flagpole, my father’s stern voice & then being bustled in & up to the nursery out of sight.”

Thankfully no one was hurt, but the incident would come back to bite Fay two months later. After he presided at a pro-McClellan rally at Faneuil Hall in Boston on 17 Sep. 1864, the Transcript printed a letter from an unnamed person reminding readers about Fay’s earlier “dishonor” and “insult” to the flag. The Democratic Boston Courier supported him, but the Transcript was unimpressed:

The Courier defends and applauds Mr. Fay for putting the American flag at half mast on the Fourth of July, and for threatening to shoot anybody who interfered “to alter the position of the flag.” […] If the party to which they belong gets into power they may have the consolation of seeing the American flag permanently at half mast, with Jeff. Davis, pistol in hand, threatening to shoot anybody who “alters its position.”

Fay wrote to the Transcript to defend himself and his patriotism. His letter was published in full, but with unflattering commentary. The paper assumed the guilt of the Charleston “traitors” and the necessity of their detention, criticized Fay’s arrogance, and called him out for hypocrisy by rattling off a litany of abuses of power by his party, the Democrats. Fay’s protest was a “desecration,” the paper said, and not the act of a “true gentleman.”

The flagpole issue would rear its ugly head again two months later, when Fay was denied a position on the Committee of Arrangements of the Boston Board of Trade, set up to honor the captain and crew of the U.S.S. Kearsarge. The Transcript (who else?) wrote, somewhat gleefully, on 11 Nov. 1864: “Mr. Fay’s friends make a great mistake in constantly crowding him before the public. He has damaged his political party and his family name, brought discredit upon the fair fame of our State, and should retire from the public view for the remainder of his days.” One of his detractors dubbed him “Half Mast Fay.”

Fay resigned from the Board of Trade in a printed circular letter dated 14 Nov. 1864. But he was not without defenders among his fellow businessmen. George B. Carhart, president of the New York and New Haven Railroad Company, wrote to Fay that his critics were “fanatics,” and abolitionist Amos Adams Lawrence also sent him an optimistic letter of support.

Joseph Story Fay was no stranger to controversy. He had lived in Savanna, Georgia, during the antebellum years and often sparred with newspaper editors there. He’d once had to refute public accusations that he was an abolitionist. (Not only wasn’t he an abolitionist, he was a slave owner!) In the case of the Woods Hole flagpole, he never wavered or apologized. As he declared in his circular letter:

I trust I shall never live to be recreant to my opposition to wrong acts, for it is above party or politics. […] I feel that I have a right to mourn over any submission to such violations of personal liberty as brought on our war for Independence. What is our nationality, unless that is its spirit? For what are we fighting to-day?

Joseph Story Fay’s papers form part of the Fay-Mixter papers at the MHS.