By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The Everett-Boyle papers fill only half of a narrow box here at the MHS, but they include a lot of terrific material from these two interrelated families. One of the family members represented in the collection is Samuel Williams Everett (1820-1862), who served during the Civil War as a surgeon in the Illinois Infantry and later as brigade surgeon. (The Everett family is originally from Boston, which is why their papers happen to be here.)

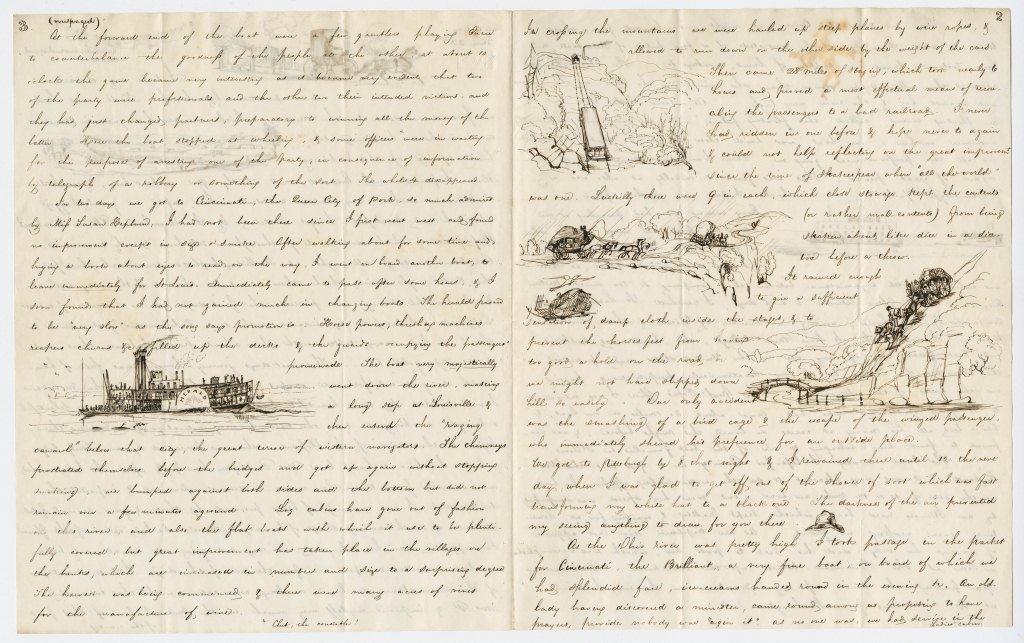

Unfortunately, we don’t have any of Everett’s war-time correspondence—at least not intact. Some letter fragments obviously date from that time, but the only complete letters by him were written between 1835 and 1851. What the collection does contain, however, are many of his fantastic drawings, beginning when he was a teenager and continuing into the war years. Here are some of my favorites:

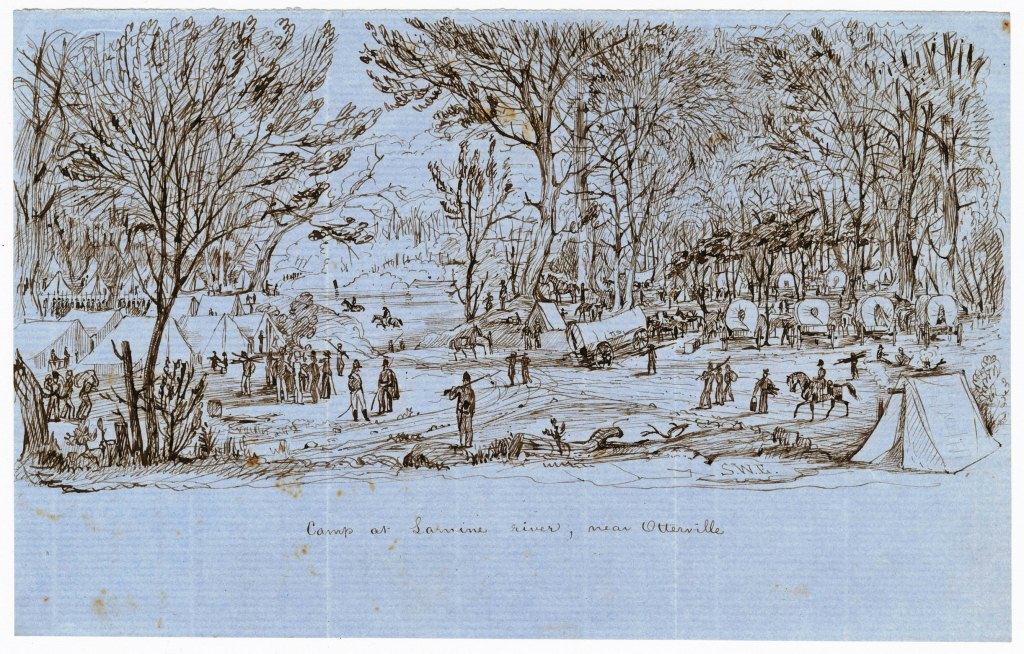

“Camp at Lamine river, near Otterville.”

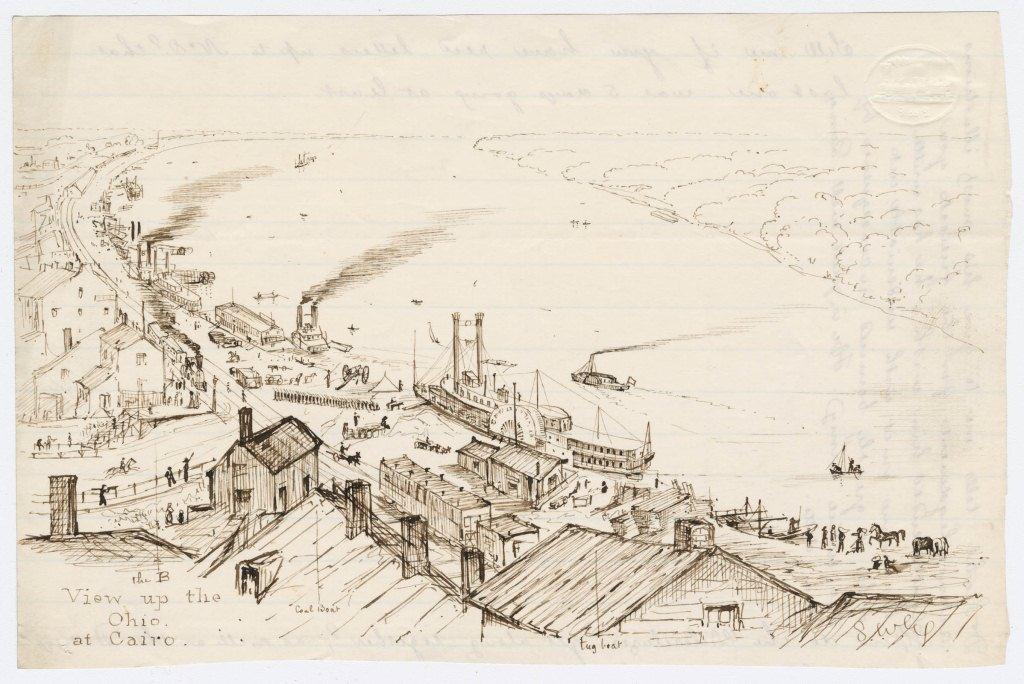

“View up the Ohio at Cairo.”

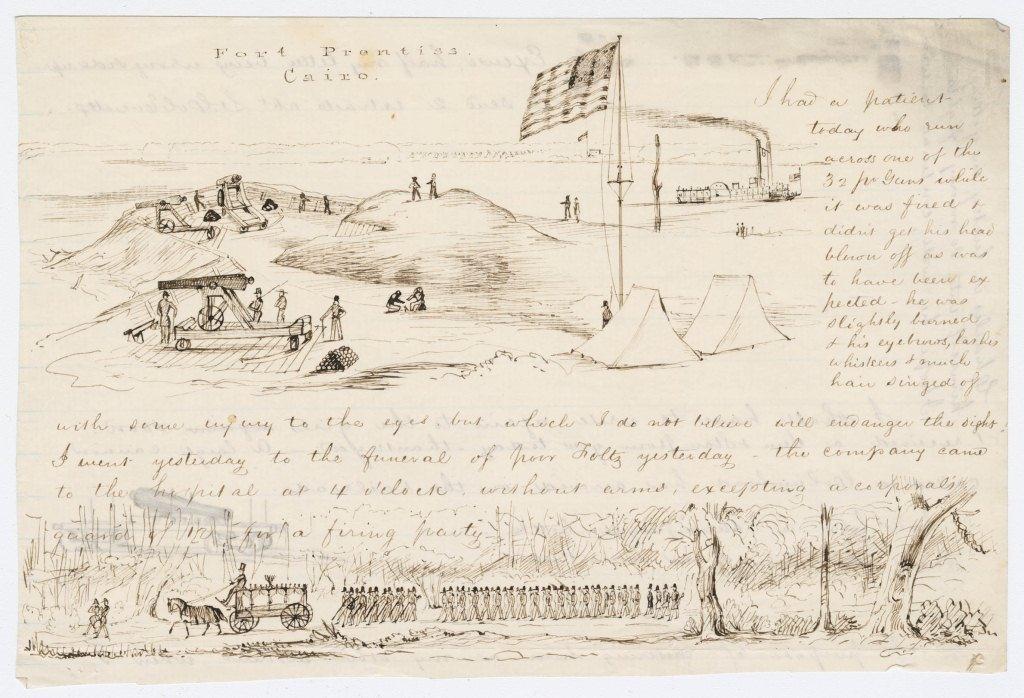

“Fort Prentiss. Cairo.”

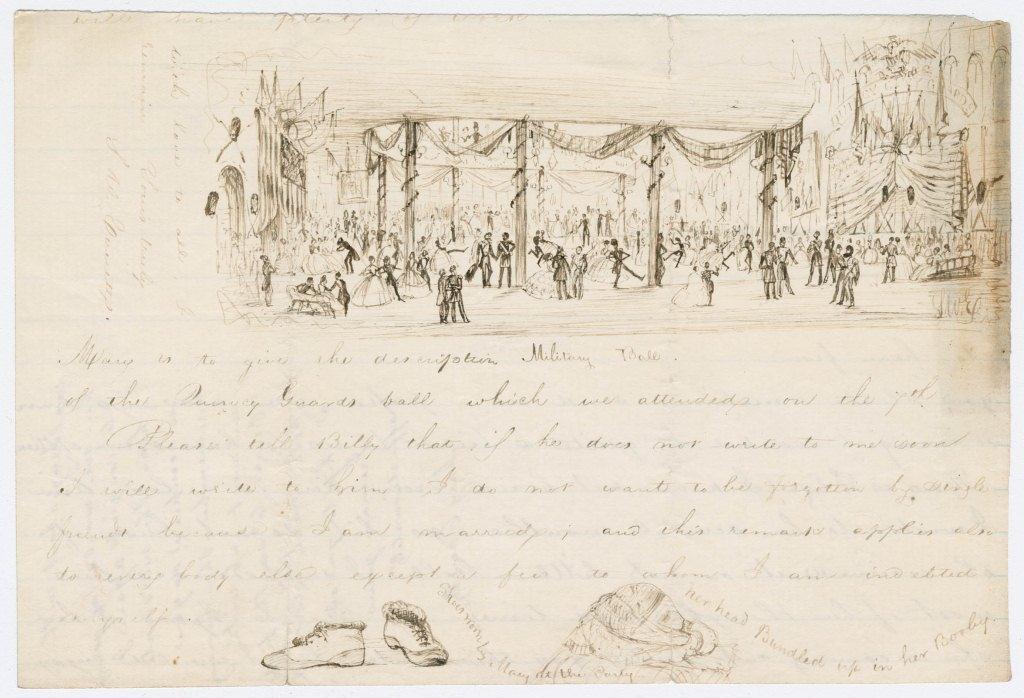

“Military Ball.”

It’s not just Everett’s artwork that makes his letters so entertaining. He was also a gifted storyteller. Even when narrating the mundane happenings of his life, he elaborated and exaggerated for comedic effect. In one letter from early 1851, he wrote about how his coat and some surgical instruments were stolen from his room, and the whole thing reads like a whodunit, complete with a whimsical “royal we”: “On that evil day the sun shone brightly, & we were tempted out to our dinner without a coat, which garment was left sweetly slumbering with the Case of Instruments in its pocket.” The story is illustrated in several panels, ending with an image of two empty nooses captioned: “View of the gallows, upon which the thieves are yet unhung.”

Everett’s description of his brother’s wedding is hilarious:

The parson retreated to avoid being knocked over in the rush of congratulation and kissing. The latter part, it was previously agreed, was to have been omitted at the particular request of the mother, the bride and the bridesmaids; but as in several rehearsals of the performance the rule had been relaxed, so it was at the ceremony and was extended to every young lady present; and repeated upon the discovery that one had been omitted.

(It was either at this wedding or shortly before that he met the bride’s cousin, his future wife, Mary Smith. He described her this way: “In spite of her common name, an uncommonly pretty girl.”)

In another letter, Everett related a humorous—though frightening—incident involving a runaway carriage, when he lost control of his horse’s reins as it raced down the street and sent bystanders scurrying for cover: “Sounds of ‘woe’ were raised from all quarters & sundry individuals appeared willing to sacrifice their lives in trying to stop the runaway, but they only stopped themselves upon re-considering the question.”

Other creative touches make his letters a real pleasure to read. When writing to his family, he addressed different paragraphs to different family members with headings like: “The Misses E.” “Anybody.” “Mrs. E.” “Ditto.” Along the top of one letter, he wrote a note that actually made me laugh out loud: “Nothing worth stopping to read in the street.”

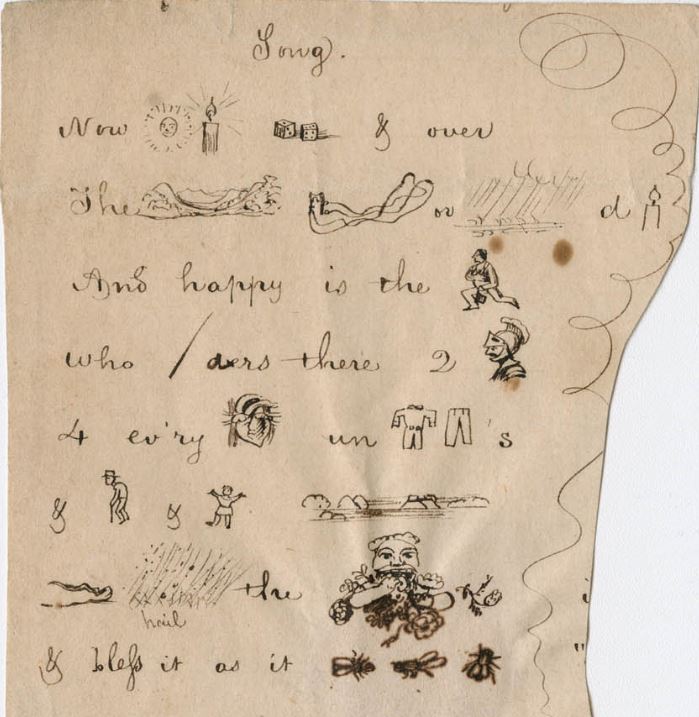

Everett also had a talent for rebuses. Anyone care to take a stab at solving either of these in the comments section below? (Hint: the second snippet is from a published work not original to Everett.)

Everett was shot and killed at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee on 6 Apr. 1862, not even one year into his military service. Multiple sources, including The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, identify him as the first Union medical officer killed in action. His “talent for drawing” was noted in his obituary in the 1864 Transactions of the American Medical Association (pp.212-4).