By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

The United States abrogated the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 regarding free trade and inshore fishing on 17 March 1866, as discussed in a prior post. The fishery arrangements then reverted back to the Treaty of 1818 agreement that secured the 3-nautical mile coastal area for resident Canadian fishermen and prohibited further inshore fishing to Americans. Canadian inshore fishing regulation transformed into a licensing business applied to American vessels at per-tonnage fee from 1866 until 1870. When Canadian authorities discarded the licensing system and began seizing American vessels over a two-year period, the need for improved arrangement led in part to the Treaty of Washington in 1871.

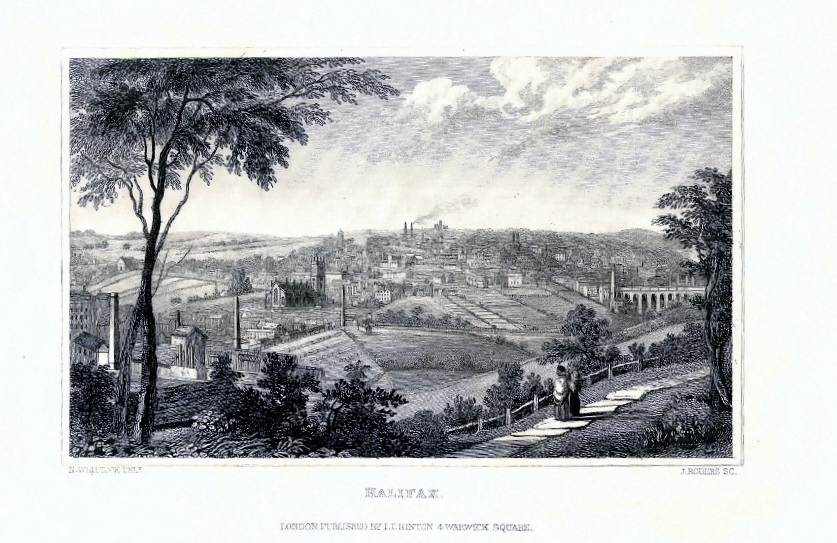

Among other issues of Northwestern border disputes and damages caused by British-built warships in the Civil War, the Treaty of Washington also addressed the future state of fishing rights between the newly formed Dominion of Canadian and the United States. The commissioners settled the issue of rights of American fishermen in Canadian waters by proposing a mixed commission meet in Halifax, Nova Scotia to determine value for reciprocal privileges. The Halifax Fisheries Commission met in June 1877. The representatives included British-Canadian Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt, American Ensign H. Kellogg, and Belgian Minister to the United States, M. Maurice Delfosse. William Henry Trescot and Richard Henry Dana, Jr., represented the United States counsel against a 5-man British-Canadian contingent.

Richard Henry Dana, Jr. of Boston, Mass. advocated that fishing in Canadian waters should remain free to Americans. “[The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854] made no attempt to exclude us from fishing anywhere within the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and it allowed no geographic limits,” he argued. “And from 1854 to 1866 we continued to enjoy and use the free fishery, as we had enjoyed and used it from 1620 to 1818.” He reasoned that the precedent for the free fishery had been established, that the fish do not adhere to ocean limits, and asked the purpose in establishing these limits:

“The right to fish in the sea is in its nature not real, as the common law has it, nor immovable, as termed by the civil law, but personal. It is a liberty. It is a franchise, or a faculty. It is not property, pertaining to or connected with the land. It is incorporeal. It is aboriginal. … These fish are not property. Nobody owns them … they belong, by right of nature, to those who take them, and every man may take them who can.”

The prose of Dana’s argument did not impress the Commission. In a split decision on 23 November 1877, the Commission determined that the United States was to pay $5,500,000 in gold to the British Government for fishing rights in Canadian waters. Despite Ensign H. Kellogg’s protest, the United States paid this sum to the British Government.