By Susan Martin, Collection Services

In this post, I’d like to introduce you to a remarkable person from one of our manuscript collections: Frances Elizabeth Gray. Elizabeth, as she was called, was born on 2 July 1811, the oldest child of Henry and Frances (Pierce) Gray, and spent most of her life in Roxbury, Mass.

What makes Elizabeth so remarkable? Her story begins with the tragic and premature death of her mother. Frances Pierce had been just 16 years old when she married Elizabeth’s father Henry in 1810. Twenty years later, just three days after giving birth to a daughter Anna Ellen, she died. She had delivered sixteen children, three of whom died in infancy. With Frances gone and Henry working as a merchant far away in New York, their daughter Elizabeth found herself with twelve—that’s right, twelve—younger siblings to raise. She was 18 years old.

Her siblings were: William (17 years old), John (16), Henry, Jr. (14), Caroline (12), Charles (11), Lydia (10), Mary (8), Frederick (6), Arthur (5), Frances (4), Horatio (15 months), and Anna Ellen (3 days). The Grays received some support from uncles, but the day-to-day care of the family fell on young Elizabeth’s shoulders.

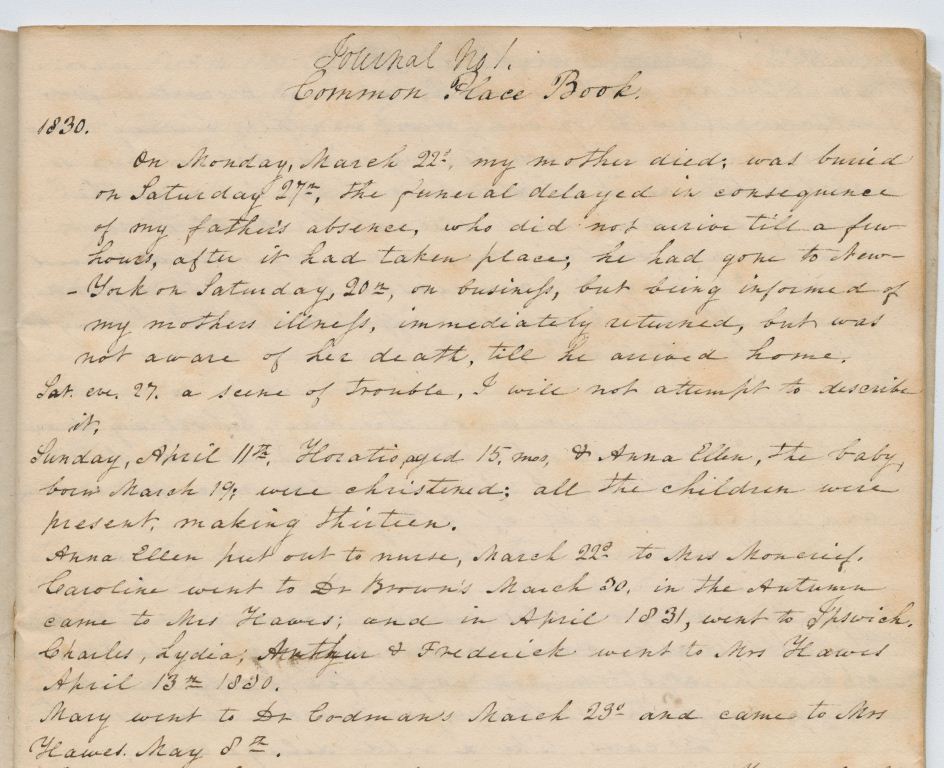

Her diaries begin with entries describing her mother’s death and the events that followed:

1830. On Monday, March 22d, my mother died; was buried on Saturday 27th, the funeral delayed in consequence of my father’s absence, who did not arrive till a few hours, after it had taken place; he had gone to New-York on Saturday, 20th, on business, but being informed of my mothers illness, immediately returned, but was not aware of her death, till he arrived home.

Sat. eve. 27. A scene of trouble. I will not attempt to describe it.

Sunday, April 11th. Horatio, aged 15. mos, & Anna Ellen, the baby, born March 19; were christened; all the children were present, making thirteen.

Anna Ellen put out to nurse, March 22d to Mrs Moncrief.

Henry Gray returned to business in New York and frequently wrote to Elizabeth with news and advice. I was prepared to dislike Henry for his absenteeism, but his letters demonstrate a respect for his daughter that impressed me. He almost always deferred to her in matters related to the children. He wrote with genuine affection and regard for her happiness, as well as confidence in her judgment. For example: “I approve your measures, not only what you have done, but what you may do.”

The rest of the correspondence consists primarily of letters to Elizabeth from her brothers William, John, and Henry, Jr. In the 1830s, the boys were living in various Massachusetts towns, where they were educated and trained for professions. My favorite correspondent, by far, is John. He often wrote to Elizabeth with desperate pleas for money, clothing, and other items, and when she sent them, he was effusive in his gratitude. Here’s part of letter dated 25 Oct. 1831:

I shall simply say I have received what you promised: viz bundle and moneys. A thousand thanks—best feelings—memorys of you—none wrecked. Indeed you have been a second mother. May the Father of Mercies, direct the early beginning of such charity, to terminate in your own personal happiness! I address him for you; for you especially, peculiarly, emphatically for you.

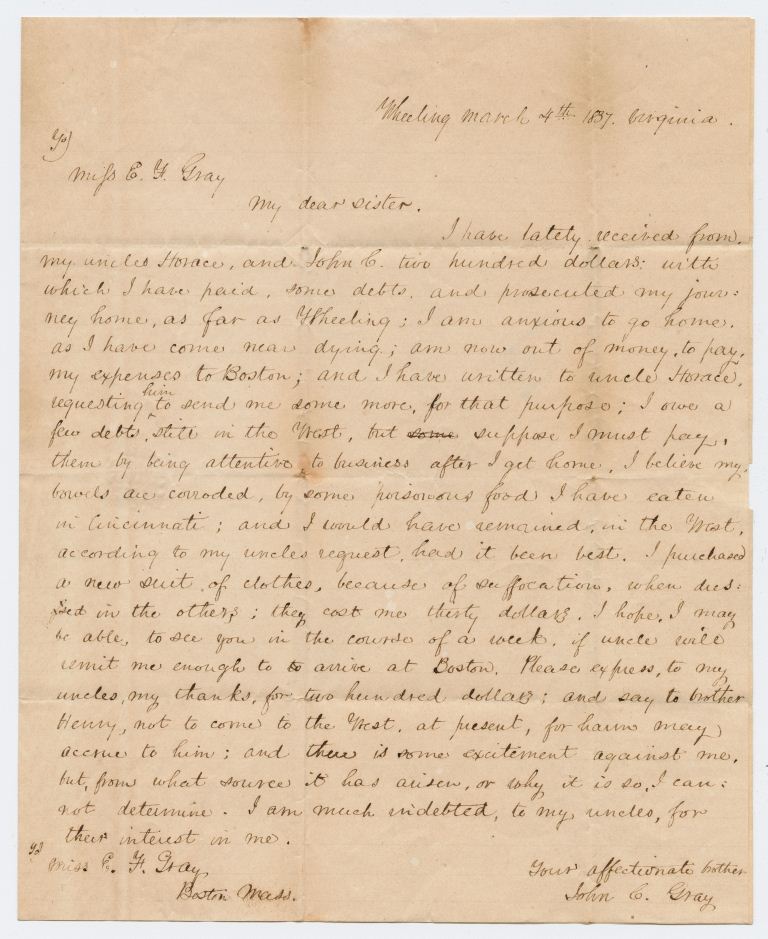

John’s life also ended prematurely, which adds to the pathos of his letters. He was studying law, but struggled with financial and emotional problems. After a failed effort to establish himself in the west, the 23-year-old John was found dead in a hotel in Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia) on the morning of 21 Mar. 1837, almost seven years to the day after his mother’s death. He’d taken a fatal dose of opium.

Caption: The last letter in the collection from John Gray, written in Wheeling.

The collection includes many letters related to John’s death, as the family struggled to come to terms with it. Henry felt that John had been the most gifted of his children, and his death was an “irreparable loss.” An inquest established that John had not died by suicide, and Dr. Eoff of Wheeling provided more details on his state of mind in the last days. In a letter to Elizabeth, he explained that John had suffered from delusions and took the opium as a curative:

He believed that one or more living animals were within him & consuming his heart, liver, &c &c & imagined that he could hear them singing &c. These impressions produced great depression of spirits & kept him continually anxious to take some medicine to remove them.

As for the other Gray siblings, my research turned up only the barest outlines of their lives. Elizabeth herself lived to be 82, but never married, though she received offers. In later life, she lived with her youngest sister Anna Ellen and helped care for her nephew, William Gray Brooks. He remembered his aunt Elizabeth fondly, writing: “I owe to her unselfish devotion and love whatever I am or know.”

Another moving tribute appears in a letter to Elizabeth from her troubled brother John, written on 16 Sep. 1834:

You say little to me of Futurity; perhaps you speak the less, because you feel the more. You have acquired fame enough. To illustrate your virtues and tenderness I point to twelve brothers and sisters. Let me partake of your advice often, that my gratitude may be strengthened, if it be capable of it.