By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

As discussed in a prior post, Great Britain previously held claim to the fish in the North Atlantic. American negotiators successfully secured the right to fish the North Atlantic in the post-Revolution negotiations at Paris in 1783:

It is agreed that the People of the United States shall continue to enjoy unmolested the Right to take Fish of every kind on the Grand Bank and on all the other Banks of Newfoundland, also in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and at all other Places in the Sea, where the Inhabitants of both Countries used at any time heretofore to fish … American Fishermen shall have Liberty to dry and cure Fish in any of the unsettled Bays, Harbors, and Creeks of Nova Scotia, Magdalen Islands, and Labrador.

As you can see, successful treaty negotiations in 1783 allowed the Americans to retain the right to fish in the region, and also to use British North American coastal lands for drying and curing, allowing them to better preserve their catches.

Yet, British impressment continued despite the stipulation that United States citizens “continue to enjoy unmolested the right to take fish.” British maritime strength relied on the ability to force able seamen of any nation into service to fight its wars and replace the dead and deserters. Well aware of the injustice of the practice, the United States House of Representatives submitted a report entitled Legislative Provision Necessary for the Relief of American Seamen Impressed into the Service of Foreign Powers on 25 February 1796. The report’s proposals were twofold: relieve impressed seamen and provide documentation of citizenship. The House committee promoted “a provision for support of two or more agents, to be appointed by the Executive, and sent, the one to Great Britain, the other to such places in the West-Indies, where the greatest number of British ships of war may resort, and to continue there for such time as the President may deem necessary.” This plan did not cease the practice of impressment. British economic sanctions against the United States and increasing American outrage regarding impressment led to the War of 1812.

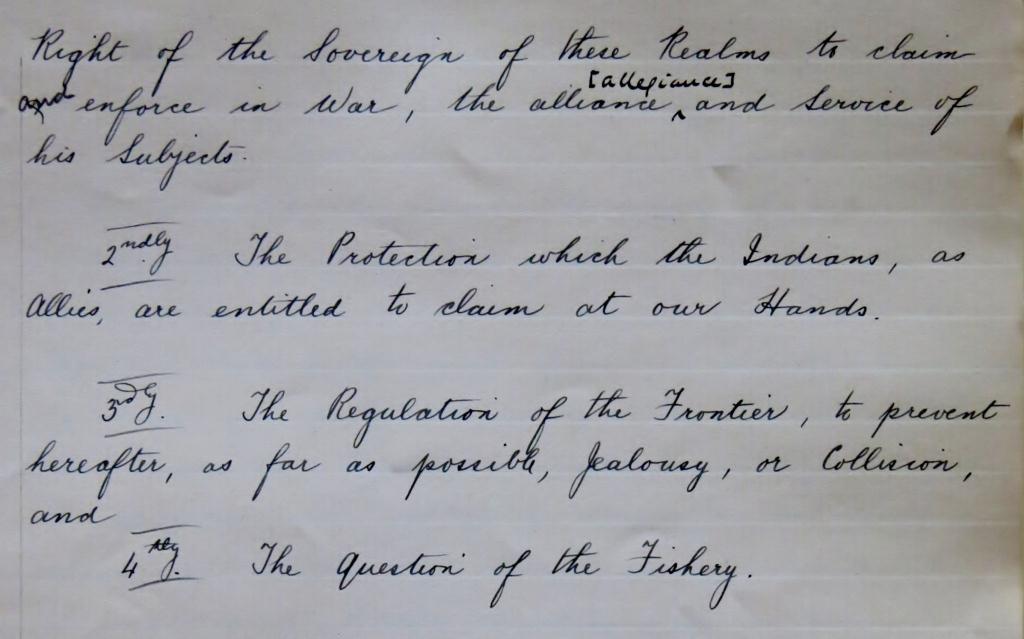

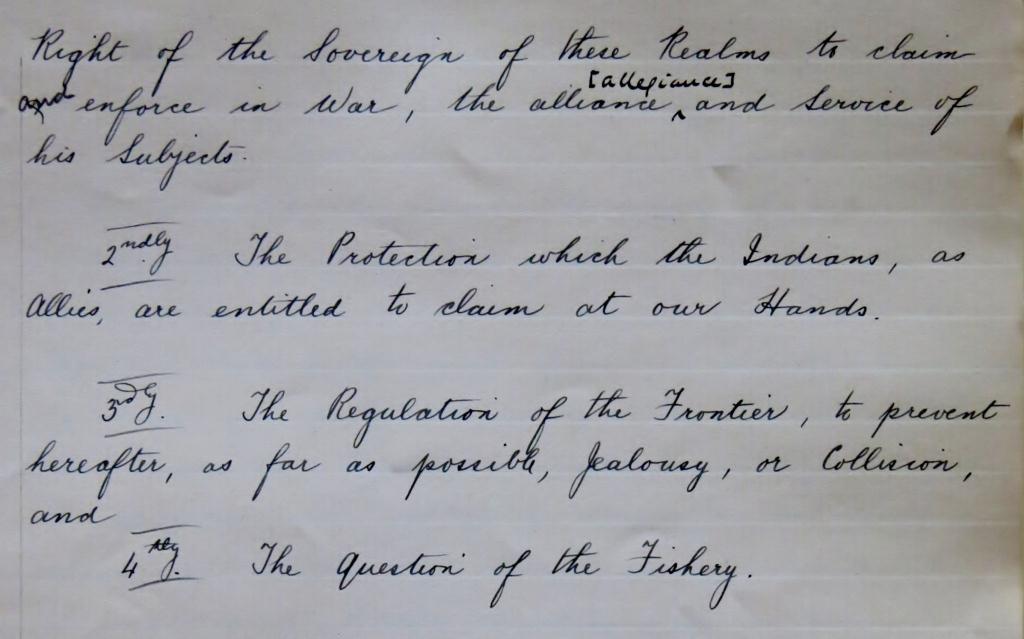

Following the British victory, the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 reversed much of the previous agreement regarding fishing rights made in 1783. Chief negotiator John Quincy Adams, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, and statesmen Henry Clay, James A. Bayard, and Jonathan Russell met with Lord James Gambier, Doctor William Adams, and Under Secretary of State Henry Goulburn in Ghent, Belgium in 1814 to negotiate a peace. The British vied for retention of gains made during the war while Americans held fast to pre-war boundaries and rights. In manuscript copies of Henry Goulburn’s correspondence held at MHS, the British negotiator outlines the important topics for discussion: British maritime rights, Indian protection, establishing borders, and fishing rights. While the third article of the Treaty of Ghent stipulated the restoration of prisoners of war, the British retained the right to impress men into maritime service.

Anglo-American land and sea disputes may have continued ad nauseam without the circumstances and consequential agreements following the War of 1812. The end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 reduced British impressment of American seamen. The Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1817 restricted naval armaments from the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain. The Treaty of 1818 resulted in the solidification of the 49th parallel as the northern land boundary between the United States and British North America. The British confirmed the United States’ right to fish the coast of Newfoundland, Magdalen Islands, and Labrador and to dry and cure in unsettled Newfoundland and Labrador. In exchange, “the United States hereby renounce for ever, any Liberty heretofore enjoyed or claimed by the Inhabitants thereof, to take, dry, or cure Fish on, or within three marine Miles of any of the Coasts, Bays, Creeks, or Harbours of His Britannic Majesty’s Dominions in America.” These agreements established important borders that remain today. This middle ground agreement between Great Britain and the United States held for nearly two decades before resuming contestation.