By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

Boundaries on land are largely man-made. These lines scribbled on paper or enclosed by transient fences signify what is claimed. Borders change over time. Geography shifts with natural disaster into or out of the ocean. Land boundaries are surprisingly fluid but not as immaterial as the open ocean, which poses the indeterminate question: Who owns the sea? Who has the right to fish the ocean?

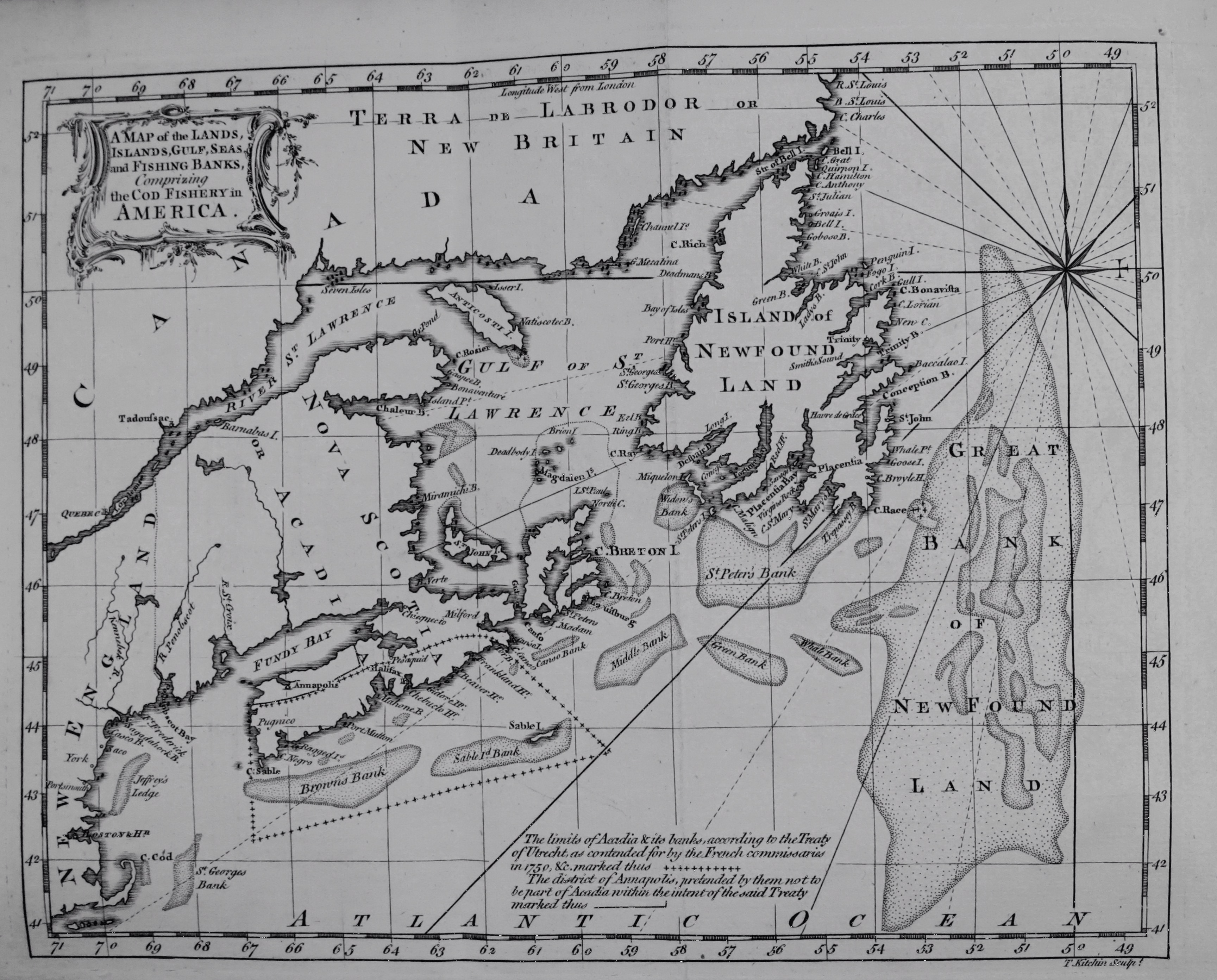

In a four-post blog series, I aim to examine the claims over the North Atlantic fishery from 1764 to 1910. I cannot identify who owns the ocean. You may want to ask Poseidon or Neptune. My goal is to tell the story of claims and contestation of this “American fishery” between Great Britain, Canada, and the United States through our collections at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The contestation truly begins with the coming of the American Revolution.

In the North Atlantic, various claims to the plentiful fishing waters off the Newfoundland coast to the tip of Cape Cod in Massachusetts Bay caused great strife between Great Britain and its colonies. Great Britain’s economy relied heavily on Atlantic fish trade especially that of dried, salted cod. The growth in population and life expectancy in New England throughout the 18th century also increased the numbers of New England fishermen and their fishing vessels, and thus increased Atlantic fishing. In response to this additional competition in the Atlantic, British fish merchants cornered the market by prevailing upon Parliament to protect their interests in the “American” fishery. To this end, Sir Hugh Palliser became Governor and Commander-in-Chief at Newfoundland in 1764 and intensified the removal of New England fishing vessels from the coastal waters in support of a British fishery in the North Atlantic.

Massachusetts resident William Bollan published a treatise entitled The Ancient Right of the English Nation to the American Fishery in the same year as Palliser’s appointment. This publication summarizes a history of naval conflict in the North Atlantic in an effort to persuade his London audience of their might over the pitiable French. In establishing the English right to this fishery, he then asks to share these waters with the enemy:

“…I cannot forbear recolleƈting that the eagles grief was encreased on her finding that she was shot with an arrow feathered from her own wing; and that my cordial wishes for the future happy fortunes of my prince and country are accompanied with concern that after obtaining so many important victories, whereby the enemy was so far enfeebled and disarmed, and the sources of her commence and naval strength brought into our possession, there should be prevailing reasons for putting into her hands so large a portion of this great fountain of maritime power.”

Bollan’s use of the eagle shot with an arrow feathered from her own wing in hindsight unintentionally reflects the growing revolutionary sentiments in the British North American colonies during the 1760s.

With tensions rising over the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765, British seizures of American fishing vessels in Newfoundland waters increased the building momentum of riotous debate over colonial rights. In the summer of 1766, Captain Hamilton of HMS Merlin boarded the colonial schooner Hawke and demanded to know what business skipper Jonathan Millet had in the Newfoundland waters. The New England fishermen were there for cod fishing. Upon the response, the captain promptly seized the vessel and fish, according to Jonathan Millet’s deposition from 13 September 1766, “…[Captain Hamilton] threatn’d that if he ever Catch’d any New England Men Fishing there again that he wou’d seize their Vefsells & Fish and Keep all the Men, beside inflicting severe Corporal Punishment on every man he took,….” Spurred by his foul treatment at the hand of the captain, skipper Millet recounted his impressment grievances to the Justices of the Peace Benjamin Pickman and Joseph Bowditch in Salem for this deposition.

A plethora of impressment grievances appear in the 1760s in the MHS collections. In fact, William Bollan personally knew of impressment as a major issue of contention. Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson wrote to Bollan in the latter’s capacity as colonial agent in London on the issue of impressment in 1756. This letter was written a decade prior to the Hawke impressment. British inattention to colonial rights and the impressment of colonial fishermen certainly led to rebellion. But the contestation over Newfoundland fishing rights continued well into the 19th century.

In the next blog post, I will examine the fishing in the Early Republic as New England fishermen become citizens of the United States, and Britain’s continued impressment until the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.