By Susan Martin, Collection Services

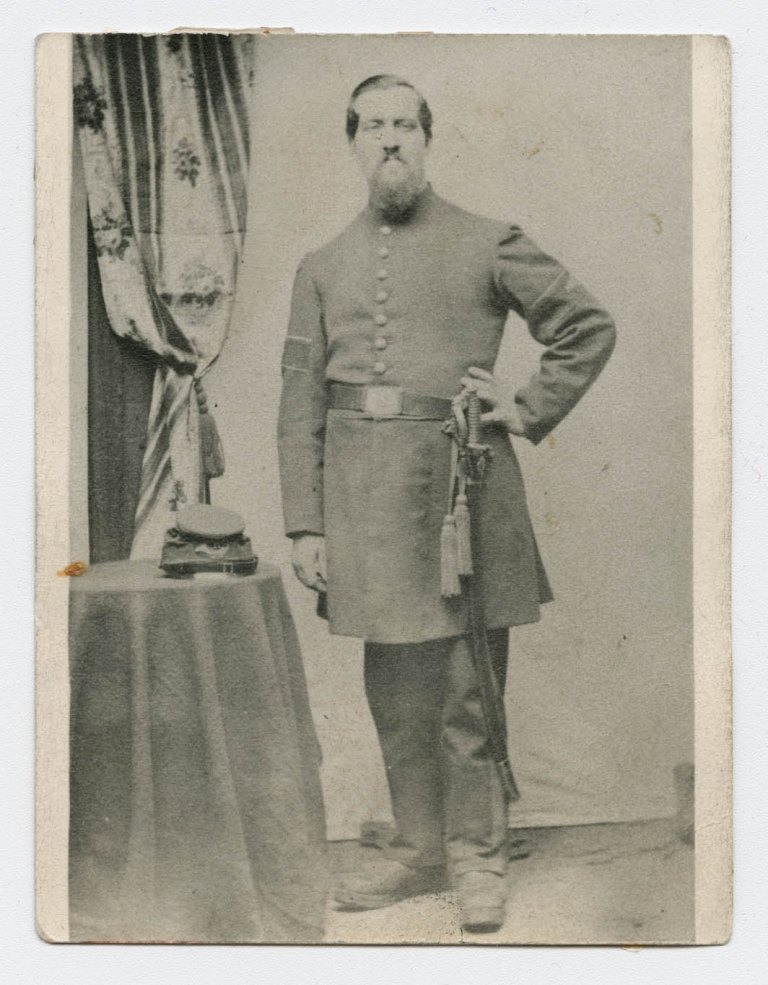

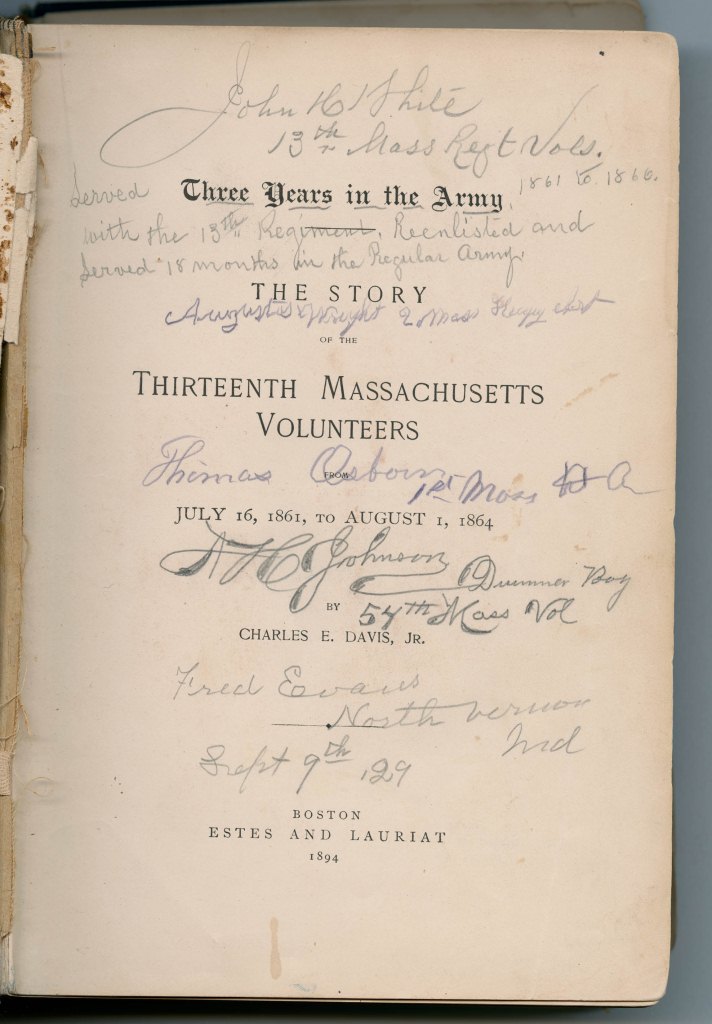

John Hill White (1835-1920) served as a hospital steward in the 13th Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War. His collection at the MHS contains a lot of fascinating material, including four diaries he kept from 1862 to 1865. But I was particularly interested in his personal copy of the book Three Years in the Army: The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers by Charles E. Davis, Jr. When White’s collection was acquired, the MHS already held a copy of this regimental history as part of its reference collection. But White’s copy is unique because he annotated many of the pages, adding valuable and sometimes hilarious running commentary in the margins.

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Many of White’s notes, probably written about 1903, identify individuals Davis had left anonymous. White also underlined and bracketed passages and added some specific dates, presumably by consulting his own diaries. But it’s his longer annotations that make for the most entertaining reading. Take, for example, this anecdote he scribbled at the bottom of page 40:

Capt Joe Coburn [Colburn], Ned Frost, John Saxton, & myself went to the hotel in town. The landlady asked Coburn if he was General Abercrombie & staff. Joe said yes, and she informed him that supper was all ready. The General had ordered the supper. We ate it, you bet, and as the general appeared at the front door we made a masterly retreat out the back door, & the general never found out who ate his supper, and did not pay for it.

And another a few pages later:

It was at Middleburg that Bryer, John King, & “Polly” Waitt got 24 good fat chickens for me. I had to present a revolver at the head of the man who owned them who politely informed me he would smash the head of the first man who took one, but the cocked revolver that he was looking into quieted him and he dropped his axe.

White had often been present at the events described in the book and used his notes to elaborate or add context. For example, a story on page 57 involves Gen. George L. Hartsuff, a kettle of beans, an irascible cook, and a case of mistaken identity. Here’s White’s version:

I saw the whole transaction. When Henry [the cook] turned around & saw the Gen’l, he straightened himself up, & saluting the Genl with the long iron spoon he held, said to him, “was that you general who wanted some of those beans?” I was the man said the general, & you can bet he got enough for a feast. The general married a Mass’t lady and there learned to love his beans.

These nostalgic “Humor in Uniform” style accounts are interspersed with others of the more heartbreaking variety. On page 78, next to the description of a particularly grueling march (at times through knee-deep water), White added:

I lost 20 lbs on this march, and was nearly starved during our 10 days marching. I was wet to the hide, for I did not have a blanket or my overcoat and the nights were cold as the devil.[…] Not a bit of fun being hungry & wet.

White’s notes reveal a lot about him and transform this printed volume into a kind of personalized history or mini-memoir. For example, he proudly starred and underlined a reference to the regimental glee club, of which he was a member. He also marked his birthday and commented on fellow soldiers. George M. Cuthbert was apparently a “great cribbage player” (p. 410), and the young drummers Ike and Sam Webster were “2 brothers who lived in Martinsburg Va. Little freckeled face boys, but good soldiers, true to the old Flag” (p. 465). Col. Richard Coulter of the 11th Pennsylvania is praised fulsomely in Davis’s text: “a better fighting man never lived” (p. 63). White agreed in the margin: “That is so.”

Unsurprisingly, White was not a fan of Gen. Jeb Stuart, who captured him with nearly 100 others on 30 Aug. 1862. According to White (p. 119), Stuart “was a damn coward, for the first shell that came from our side sent him down the hill as if the devil was after him.” But another Confederate general, Roger A. Pryor, “was a perfect gentleman and did all he could to make our wounded as comfortable as possible, under the circumstances.”

When I compared White’s annotations to the corresponding entries in his diaries, I appreciated this volume even more. In most cases, what he wrote here is much richer in detail. However, one fascinating fact is revealed in his diaries: he was present at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. on 14 Apr. 1865 and witnessed the assassination of Abraham Lincoln! Here’s his description of that event:

Went to Fords Theatre. Miss Laura Keenes Benefit. Mary C. with me. At 25 minutes past 10, heard a pistol shot and immediately J Wilkes Booth jumped from the box in which the President and wife were, exclaiming, “Sic Semper Tyrannus, Virginia is avenged.[”] He had shot the President in the head, and stab[b]ed Major Rathborn [Rathbone] with a dirk. He escaped by the stage door. All was excited. Men & women shed tears. Got home at 11 p.m. No sleep all night. Secretary Seward and sons stab[b]ed by an accomplice of Booth. A general slaughter of the whole Cabinet attempted.

The next day, he wrote:

The President died at 20 past 7 am. Went to town saw the body of the President being conveyed to the White House. Went to town in the afternoon. All business suspended and all the public buildings stores and houses dressed in mourning. Sad, sad day, for our Country.[…] Report of Booth having been captured. Andrew Johnson took the oath of office as President at 11 am this day at the Kirkwood House.