By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Thursday, March 2d.

Thank God for the triumphant progress of the Union arms, the occupation of Savannah, Columbia, Charleston, and Wilmington.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Thank God for the triumphant progress of the Union arms, the occupation of Savannah, Columbia, Charleston, and Wilmington.

By Dan Hinchen

On Tuesday, 31 March, come in at 5:15PM for an Early American History Seminar called “Frontiers and Geopolitics of Early America.” This installment is presented by Patrick Spero of Williams College with Kate Grandjean, Wellesley College, providing comment. The seminar is free and open to the public though an RSVP is required. You can also subscribe to receive advance copies of the seminar papers.

Then, on Wednesday, 1 April, pack a lunch and come by at noon for a Brown Bag talk given by Krista Kinslow of Boston Univesity. Ms. Kinslow will discuss her current research project, “Contesting the Centennial: Civil War Memory at the 1876 World’s Fair.” As always, this brown bag talk is free and open to the public and starts at 12:00PM. No fooling!

Also on Wednesday, 1 April, is the second installment in the Lincoln & the Legacy of Conflict Series. Join us as author and editor Richard Brookhiser presents “Founders’ Son: A Portrait of Abraham Lincoln,” the title of his newest book. Registration is required for this event with a fee of $20 (no charge for Fellows and Members). The events begins at 6:00PM with a pre-talk reception starting at 5:30PM.

On Thursday, 2 April, is the next Biography Seminar, this time featuring Dave Sobel, author of Longitude and Galileo’s Daughter, in conversation with Susan Ware. The seminar is free and open to the public though an RSVP is required. You can also subscribe to receive advance copies of the seminar papers. The program begins at 5:30PM.

And on Saturday, 4 April, we have two items on the calendar. First is our weekly tour, the History and Collections of the MHS, a 90-minute docent-led walk through our public rooms. The tour is free, open to the public, with no need for reservations. If you would like to bring a larger party (8 or more), please contact Curator of Art Anne Bentley at 617-646-0508 or abentley@masshist.org. While you’re here you will also have the opportunity to view our current exhibition, “God Save the People!” which explores events leading up to the American Revolution.

Finally, on Saturday afternoon, starting at 1:00PM is “Begin at the Beginning: Boston’s Founding Documents.” This is the second of our lively MHS/Partnership of Historic Bostons co-hosted discussions, this time focusing on John Winthrop’s journal. The discussion is open to all, though the discussion group is limited to 15; available on a first come first served basis. Links to the documents are available at the registration site. (Registration for this discussion group is coordinated by the Partnership of Historic Bostons).

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

As a manuscript processor here at the MHS, I have the opportunity to meet new people every day. Well, okay, most of them died a long time ago, but that doesn’t make them any less interesting! One of the best parts of processing and cataloging a new collection is getting to know the personal stories behind the letters, diaries, and other papers. I almost always uncover something unexpected.

Case in point: a small collection recently donated to the MHS consists primarily of letters written by Sarah Louisa “Louly” (Hickman) Smith to her sister Anna Maria. Now, I knew that Louly had become a published poet in her teens before her untimely death at the age of 20, and her letters reveal a remarkable young woman. But I was also curious about Anna Maria. The collection contains letters written to her, but none by her, so she seemed more elusive.

The first clue I had about her life was her name. She was born Anna Maria Campbell Hickman on 23 July 1809. Simple enough so far, but it gets trickier. She married three times (and outlived all her husbands): first a Mr. Otis, then Mr. Mead, and finally Mr. Chalmers. For those of you at home keeping score, that would make her Anna Maria Campbell Hickman Otis Mead Chalmers. (She’s generally referred to as Anna Maria Mead Chalmers.)

The more I learned about Anna Maria’s life, the more interesting it became. Originally from Newton, Mass., she studied under some of the best teachers in the Boston area and spent a year with an aunt and uncle in Savannah, Ga. before marrying a young Boston lawyer named George Alexander Otis, Jr. in Feb. 1830. Unfortunately her husband died of consumption the following year when their son was only seven months old. George’s death was followed closely by that of her beloved sister Louly on 12 Feb. 1832.

In the mid-1830s, Anna Maria lived in Newton with her mother and young son (her father had died in 1824) and wrote several children’s books for the American Sunday-School Union. She met and married the Rev. Zachariah Mead, a Virginian, moving with him to Richmond in 1837. The couple had two sons and a daughter: Edward C., William Z., and Anna Louisa Mead. Zachariah died (also of consumption) on 27 Nov. 1840, and Anna Maria, still just 31 years old, was now twice widowed and the mother of four young children.

For about a year, she took over Zachariah’s editorship of the Southern Churchman, to which she had often contributed, before selling the paper and embarking on arguably the most significant chapter of her life. On 4 Oct. 1841, she opened a boarding school for girls in Richmond, which she would run for 12 years to great acclaim. During her tenure, hundreds of girls were educated in subjects as wide-ranging as history, literature, theology, the sciences, mathematics, languages, music, art, etc., all in accordance with Christian principles. An 1842 advertisement in the Southern Literary Messenger described the school’s mission this way: “to form the female character for its high duties here and its still higher destination hereafter.” Anna Maria also continued to write devotional fiction and articles.

Tragedy struck again when her youngest child and only daughter, three-year-old Anna Louisa Mead, died on 4 Dec. 1843. Her mother followed four years later. So, by the 1850s, Anna Maria had buried her parents, her sister, two husbands, and a daughter. She retired as schoolmistress of “Mrs. Mead’s School” and, on 3 Jan. 1856, at the age of 46, married her third husband, David Chalmers. He was a widower and a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, and he owned a large Halifax County plantation.

As a wealthy planter, David Chalmers was, unsurprisingly, an enslaver, and Anna Maria became “a true Virginia matron.” How did she feel about the South’s so-called “peculiar institution”? According to her son Edward in his comprehensive 1893 biography, she opposed slavery and often spoke out against it, but took no active part in the fight for abolition. She preferred to leave the matter to God. And while her husband advocated secession, she dreaded the coming war between the states. With very good reason, it turned out: the Civil War would find her with one son serving in the Union army, another in the Confederate army, and all of her northern property under threat of confiscation.

Her oldest son, George Alexander Otis (1830-1881), was a surgeon with the 27th Massachusetts Volunteers and the U.S. Volunteers. Her third and youngest son, William Zachariah Mead (1838-1864), fought for the Confederacy and was killed on 14 May 1864 in the Battle of Resaca, Ga.

Anna Maria traveled north in 1863 to protect her property there and stayed in New York until the end of the war. In 1865, she returned to Virginia, where she would spend years helping the poor, educating formerly enslaved people, and writing. She died on 8 Dec. 1891, outliving her third husband by 16 years and her oldest son George by ten, and survived by only one of her children, Edward Campbell Mead (1837-1908).

In her 82 years of life, Anna Maria Mead Chalmers was many things: a writer, an editor, a teacher, a philanthropist; a sister, a mother, and the wife (and widow) of a lawyer, a minister, and a farmer; a Northerner and a Southerner. It’s remarkable to find so much of American history all rolled up into one person!

By Dan Hinchen

On Tuesday, 24 March, come in at 5:15PM for a seminar from the Immigration and Urban History series. Come listen as Thomas Chen from Brown University discusses “Remaking Boston’s Chinatown: Race, Place, and Redevelopment after World War II.” Jim Vrabel, author of A People’s History of the New Boston will be on-hand to provide comment. Seminars are free and open to the public; RSVP required. Subscribe to receive advance copies of the seminar papers.

Looking for some lunchtime learning? If so, come in on Wednesday, 25 March, for “Allegiance and Protection: The Problem of Subjecthood in the Glorious Revolution, 1680-1695.” This Brown Bag talk is presented by Alex Jablonski, State University of New York at Binghamton, and is free and open to the public. So pack a lunch and come on down!

And on Thursday, 26 March, join us at 6:00PM for the first event in a series called Lincoln and the Legacy of Conflict. “A Civil Conversation” is an author talk and conversation featuring James McPherson and Louis Masur, facilitated by Carol Bundy. The program is open to the public at a fee of $20 (no charge for Fellows and Members). Registration is required; please RSVP. A pre-talk reception begins at 5:30PM.

Part 2 of Lincoln and the Legacy of Conflict takes place on Saturday, 28 March, this time taking the form of a Teacher Workshop. “Emancipation & Assassination: Remembering Abraham Lincoln” will highlight digital resources available from the MHS and Ford’s Theatre, Lincoln-related treatures from the Society’s collections, and discover methods for teaching Lincoln’s life and legacy. A fee of $25 includes lunch and materials. For more information, contact the education department at education@masshist.org or 617-646-0557. To register, complete our Registration Form and send it to the education department at education@masshist.org.

Lastly, there is also a tour on Saturday, 28 March. Beginning at 10:00AM, The History and Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society Tour is a 90-minute docent-led walk through our public rooms. The tour is free, open to the public, with no need for reservations. If you would like to bring a larger party (8 or more), please contact Curator of Art Anne Bentley at 617-646-0508 or abentley@masshist.org.

While you’re here you will also have the opportunity to view our current exhibition, “God Save the People!” which explores events leading up to the American Revolution.

By Peter K. Steinberg, Collection Services

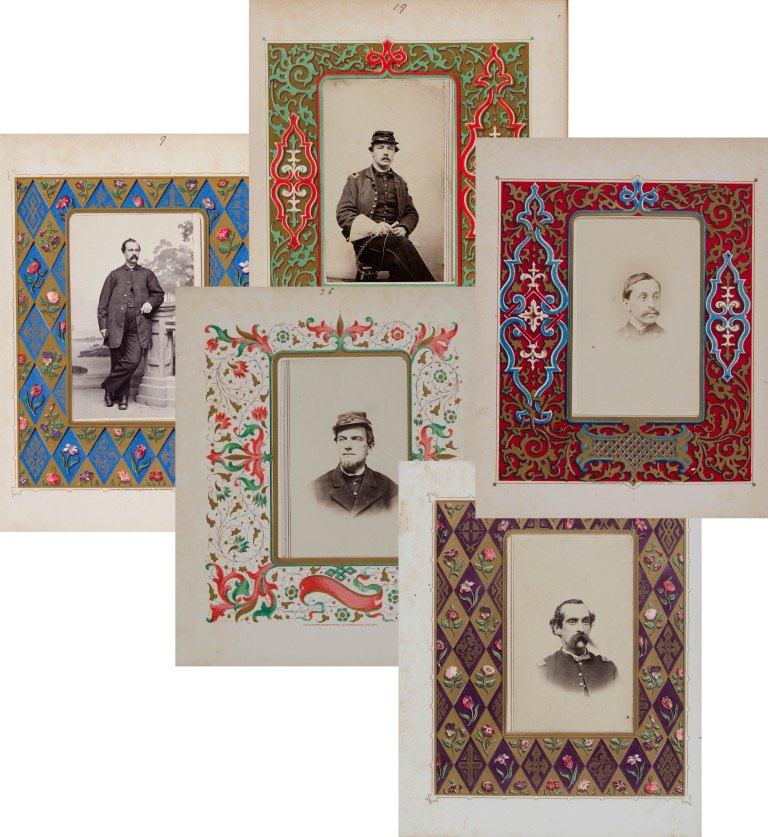

Collection Services at the Massachusetts Historical Society has recently created a collection guide for, and fully digitized, the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment carte de visite album, ca. 1864-1865 (Photograph Collection 228).

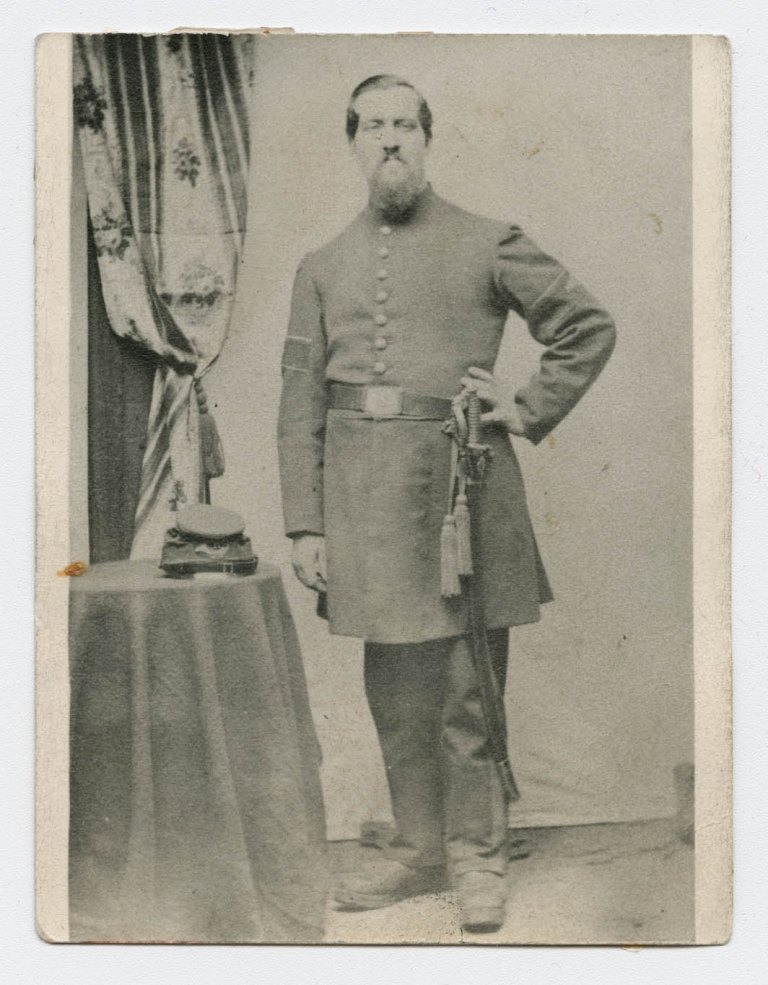

The 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment was a “colored volunteer” regiment active from 9 January 1864-31 October 1965. Formed at Camp Meigs, Readville, Massachusetts, was commanded by some notable sons of Massachusetts including Charles Francis Adams Jr., Henry S. Russell, Charles Pickering Bowditch, and Henry Pickering Bowditch. The regiment saw some action in the war, notably in a battles which took place at Baylor’s Farm and the Siege of Petersburg in Virginia.

This collection consists of a photograph album containing 46 carte de visite photographs of officers from the regiment. In addition to those named above, the regiment included Edward Jarvis Bartlett, Daniel Henry Chamberlain, Patrick Tracy Jackson, and others. The album includes a two-page handwritten index which identifies all but one of the photographs. Each image appears on a page beautifully bordered, as can be seen in the examples presented here.

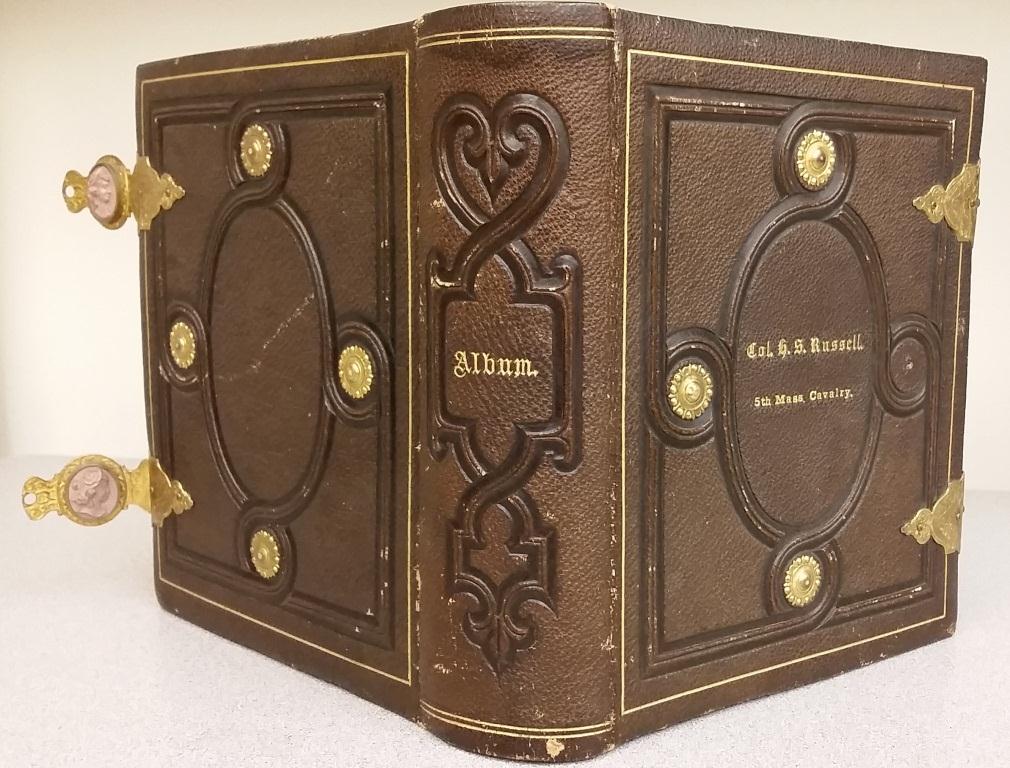

The cover of the album, also stunning, is embossed: “Col. H. S. Russell. 5th Mass Cavalry” and features the original, still-functioning brass clasps to keep the album closed. Henry S. Russell (1838-1905), an 1860 graduate of Harvard University, served several ranked positions in the Union Army reaching Lieutenant-Colonel of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry and Brigadier-General of the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. In 1864, Russell married Mary Hathaway Forbes, the daughter of the influential Boston businesman, railroad magnate, and abolitionist John Murray Forbes, and was a cousin of Robert Gould Shaw, Colonel of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Another family connection, but this time within the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment, were the brothers Henry Pickering Bowditch (1840-1911) and his younger brother Charles Pickering Bowditch (1842-1921). Both were Harvard educated; Henry being a physician and physiologist as well as dean of Harvard Medical School, and Charles becoming a financier, archaeologist and linguistics scholar.

This is the seventh fully digitized Civil War photograph album at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The MHS has additional fully digitized Civil War materials available, as well. Further Reading: Morse, John T., Jr. “Henry Sturgis Russell.” In Sons of the Puritans: A Group of Brief Biographies. Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1908:153-162.

By Dan Hinchen

Come by on Tuesday, 17 March, for another Environmental History Seminar. This time around, Katherine Johnston of Columbia University presents “An Enervating Environment: Altered Bodies in the Lowcountry and the British West Indies.” Conevery Bolton Valencius from the University of Massachusetts – Boston will provide comment. The talk begins at 5:15PM and is free and open to the public; RSVP required. Subscribe to receive advance copies of the seminar papers. Rescheduled from February 10.

On Wednesday, 18 March, bring a lunch at 12:00PM for “Networks of Faith and Finance: Boston’s Scottish Exile Community in the Later Seventeenth Century.” This Brown Bag talk is given by Craig Gallagher of Boston College. This event is free and open to the public.

Also on Wednesday, 18 March, is the third installment of the Landscape Architecture Series. This time around, independent author Elizabeth Hope Cushing presents “Landscape Architect Arthur Shurcliff.” There is a reception for the event at 5:30PM with the talk beginning at 6:00PM. The talk is open to the public with a fee of $10 (no charge for Fellows and Members of the MHS, Mount Auburn Cemetery and the Nichols House Museum). Registration is required; please RSVP.

And on Saturday, 21 March, come by for History and Collections of the MHS, a 90-minute, docent-led tour that explores the public space at the Society. Hear a bit about the collections, history, art, and architecture at 1154 Boylston Street. These tours are free and open to the public with no need to set an appointment for individuals and small groups. Parties of 8 or more should contact Art Curator Anne Bentley in advance at 617-646-0508 or abentley@masshist.org.

Finally, don’t forget to stop in and view our current exhibition! “God Save the People! From the Stamp Act to Bunker Hill” is open to the public Mon-Sat, 10:00AM-4:00PM, free of charge.

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

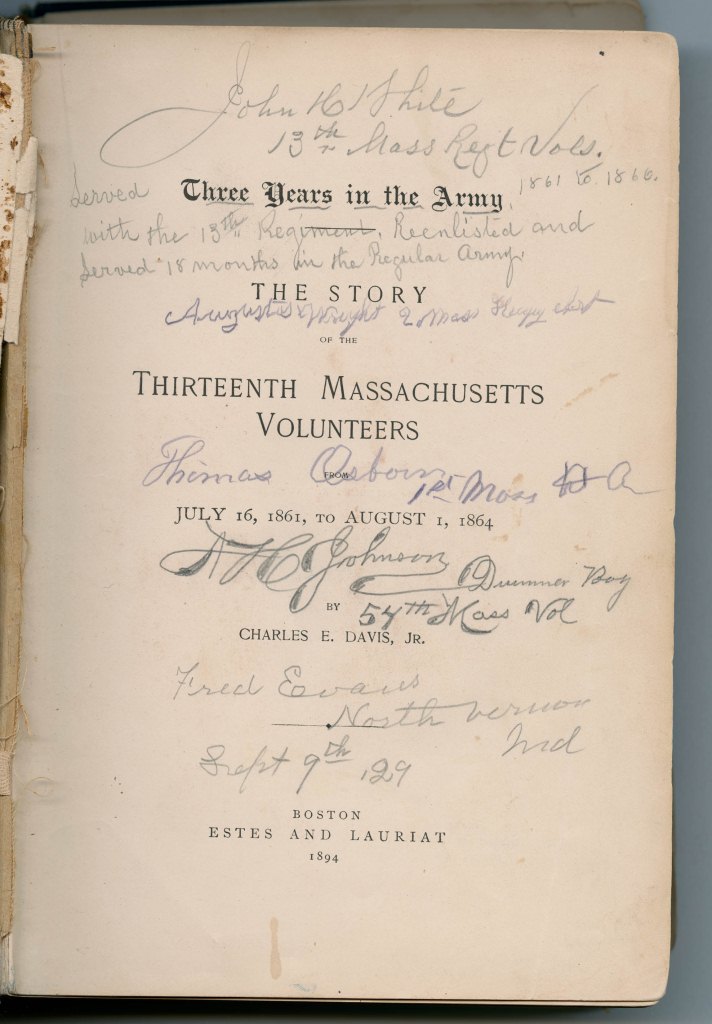

John Hill White (1835-1920) served as a hospital steward in the 13th Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War. His collection at the MHS contains a lot of fascinating material, including four diaries he kept from 1862 to 1865. But I was particularly interested in his personal copy of the book Three Years in the Army: The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers by Charles E. Davis, Jr. When White’s collection was acquired, the MHS already held a copy of this regimental history as part of its reference collection. But White’s copy is unique because he annotated many of the pages, adding valuable and sometimes hilarious running commentary in the margins.

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Many of White’s notes, probably written about 1903, identify individuals Davis had left anonymous. White also underlined and bracketed passages and added some specific dates, presumably by consulting his own diaries. But it’s his longer annotations that make for the most entertaining reading. Take, for example, this anecdote he scribbled at the bottom of page 40:

Capt Joe Coburn [Colburn], Ned Frost, John Saxton, & myself went to the hotel in town. The landlady asked Coburn if he was General Abercrombie & staff. Joe said yes, and she informed him that supper was all ready. The General had ordered the supper. We ate it, you bet, and as the general appeared at the front door we made a masterly retreat out the back door, & the general never found out who ate his supper, and did not pay for it.

And another a few pages later:

It was at Middleburg that Bryer, John King, & “Polly” Waitt got 24 good fat chickens for me. I had to present a revolver at the head of the man who owned them who politely informed me he would smash the head of the first man who took one, but the cocked revolver that he was looking into quieted him and he dropped his axe.

White had often been present at the events described in the book and used his notes to elaborate or add context. For example, a story on page 57 involves Gen. George L. Hartsuff, a kettle of beans, an irascible cook, and a case of mistaken identity. Here’s White’s version:

I saw the whole transaction. When Henry [the cook] turned around & saw the Gen’l, he straightened himself up, & saluting the Genl with the long iron spoon he held, said to him, “was that you general who wanted some of those beans?” I was the man said the general, & you can bet he got enough for a feast. The general married a Mass’t lady and there learned to love his beans.

These nostalgic “Humor in Uniform” style accounts are interspersed with others of the more heartbreaking variety. On page 78, next to the description of a particularly grueling march (at times through knee-deep water), White added:

I lost 20 lbs on this march, and was nearly starved during our 10 days marching. I was wet to the hide, for I did not have a blanket or my overcoat and the nights were cold as the devil.[…] Not a bit of fun being hungry & wet.

White’s notes reveal a lot about him and transform this printed volume into a kind of personalized history or mini-memoir. For example, he proudly starred and underlined a reference to the regimental glee club, of which he was a member. He also marked his birthday and commented on fellow soldiers. George M. Cuthbert was apparently a “great cribbage player” (p. 410), and the young drummers Ike and Sam Webster were “2 brothers who lived in Martinsburg Va. Little freckeled face boys, but good soldiers, true to the old Flag” (p. 465). Col. Richard Coulter of the 11th Pennsylvania is praised fulsomely in Davis’s text: “a better fighting man never lived” (p. 63). White agreed in the margin: “That is so.”

Unsurprisingly, White was not a fan of Gen. Jeb Stuart, who captured him with nearly 100 others on 30 Aug. 1862. According to White (p. 119), Stuart “was a damn coward, for the first shell that came from our side sent him down the hill as if the devil was after him.” But another Confederate general, Roger A. Pryor, “was a perfect gentleman and did all he could to make our wounded as comfortable as possible, under the circumstances.”

When I compared White’s annotations to the corresponding entries in his diaries, I appreciated this volume even more. In most cases, what he wrote here is much richer in detail. However, one fascinating fact is revealed in his diaries: he was present at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. on 14 Apr. 1865 and witnessed the assassination of Abraham Lincoln! Here’s his description of that event:

Went to Fords Theatre. Miss Laura Keenes Benefit. Mary C. with me. At 25 minutes past 10, heard a pistol shot and immediately J Wilkes Booth jumped from the box in which the President and wife were, exclaiming, “Sic Semper Tyrannus, Virginia is avenged.[”] He had shot the President in the head, and stab[b]ed Major Rathborn [Rathbone] with a dirk. He escaped by the stage door. All was excited. Men & women shed tears. Got home at 11 p.m. No sleep all night. Secretary Seward and sons stab[b]ed by an accomplice of Booth. A general slaughter of the whole Cabinet attempted.

The next day, he wrote:

The President died at 20 past 7 am. Went to town saw the body of the President being conveyed to the White House. Went to town in the afternoon. All business suspended and all the public buildings stores and houses dressed in mourning. Sad, sad day, for our Country.[…] Report of Booth having been captured. Andrew Johnson took the oath of office as President at 11 am this day at the Kirkwood House.

By Dan Hinchen

Filibuster, n. 1. An irregular military adventurer, esp. one in quest of plunder; a freebooter; — orig. applied to buccaneers infesting the Spanish American coasts; later, an organizer or member of a hostile expedition to some country or countries with which his own is at peace, in contravention of international law.

On September 12, 1860, an American lawyer and journalist, an adventurer and filibuster, was executed by firing squad in Trujillo, Honduras. This is his story in brief.

William Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824. Pushed by his parents to a good education, he graduated from the University of Nashville at the age of 14. By 1843, at 19, Walker received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He continued his medical education in Paris and toured several cities in Europe before returning to Nashville to practice.

Dissatisfied with his career in medicine, Walker changed his focus to law and, shortly after taking up studies, moved to New Orleans. While he attained the bar in Louisiana, his practice there was even briefer than his medical practice and he soon moved into the field of journalism. In the winter of 1848, Walker became an editor and proprietor of the conservative New Orleans Crescent.

The following year, like so many other intrepid young men, Walker responded to the lure of the West and settled in San Francisco, arriving in June, 1850. He continued his work as a journalist, speaking loudly against the judicial authorities in San Francisco for failure to roll back a tide of lawlessness and crime. His vocal stance raised the ire of district judge Levi Parsons who declared the press a nuisance and, after much wrangling, judged Walker guilty of contempt and set a fine on him. Now, Walker’s legal experience came to the fore as he defended himself in open court against the charges, with much popular support, and was ultimately vindicated.

Shortly after, Walker moved to the nearby and quickly growing town of Marysville where he practiced law with Henry Watkins. By this time, many men of California were already engaging in filibustering in Latin America. This practice, prominent during the 1850s, was an aggressive and idealized effort to expand the influence of the United States in fulfillment of manifest destiny.

Over the next several years, Walker pursued this activity with fervor. In 1853 he attempted an invasion of Mexico with a small band of men, barely escaping alive. The United States tried him in violation of the neutrality act but he was quickly exonerated. In 1855, he set his sights on Nicaragua. This locale was coveted by many as the key to linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. No less a man than Cornelius Vanderbilt invested heavily in transporting goods across the narrow country.

Landing with a small force of Americans, Walker supplemented his force with sympathetic liberal Nicaraguans and demanded independent command. With a lot of luck and small amount of daring, Walker and his men took the city of Granada and made hostages of its conservative leaders.

Over the next several months, Walker used various schemes and local proxies to consolidate power in his own hands, eventually raising the alarm in neighboring Central American countries. In April 1856, Costa Rica occupied the Nicaraguan city of Rivas in order to drive Walker out but, with the aid of an outbreak of cholera, he forced them into retreat.

Throughout the next year, Walker’s course of action greatly alienated him from his supporters in American business. So it was with the financial backing of Vanderbilt that, in spring of 1857, an alliance of Central American countries besieged him at Rivas, forcing him to surrender to an American naval officer, at which time he and his men were delivered out of the country.

Still, he was not finished. By this time, Walker was something of a folk hero in the United States, meeting acclaim wherever he went. In November 1857, he tried to invade and was met by the US Navy which forced a quick surrender. In 1860 he made one last effort. This time, the Royal Navy captured him and delivered him to the nearest authorities, the Hondurans. In September of that year, William Walker finally met his end.

The story of William Walker was unknown to me until I recently watched a film from 1987 called simply Walker, with Ed Harris in the title role and directed by Alex Cox. Though a fictional take on the actions of the man, it raised my awareness and piqued my curiosity. If you are interested in learning more about Walker and other 19th century filibusters, see below for some resources

Sources at the MHS

– The destiny of Nicaragua: Central America as it was, is, and may be, Boston: S.A. Bent & Co., 1856.

– Wells, William V., Walker’s expedition to Nicaragua…, New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1856.

Useful online resources

– Stiles, T.J., “The Filibuster King: The Strange Career of William Walker, the Most Dangerous International Criminal of the Nineteenth Century,” History Now 20 (Summer 2009). The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.gilerlehrman.org/history-by-era/jackson-lincoln/essays/filibuster-king-strange-career-william-walker-most-danerous-i

– Tirmenstein, Lisa, “Costa Rica in 1856: Defeating William Walker While Creating a National Identity,” Accessed March 12, 2015. http://jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu/FieldCourses00/PapersCostaRicaArticles/CostaRicain1856.Defeating.html

– Judy, Fanna, “William Walker,” The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist1/walker.html

By Dan Hinchen

On Tuesday, 10 March, there is an Environmental History Seminar beginning at 5:15PM. All are welcome to join us for “Fear of an Open Beach: The Privatization of the Connecticut Shore and the Fate of Coastal America.” This seminar features Andrew W. Kahrl of the University of Virginia, with Karl Haglund, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, providing comment. Seminars are free and open to the public; RSVP required. Subscribe to receive advance copies of the seminar papers.

Then, on Wednesday, 11 March, is the next installment of the Landscape Architecture Series. In this program, Keith Morgan, Director of Architectural Studies – Boston University, presents “The Brookline Troika: Olmsted, Richardson, Sargent and the Planning of a ‘Model Community.'” A pre-talk reception begins at 5:30PM and the talk begins at 6:00PM. This talk is open to the public with a fee of $10 (no charge for Fellows and Members of the MHS, Mount Auburn Cemetery and the Nichols House Museum). Registration is required; Please RSVP.

And on Saturday, 14 March, come in at 10:00AM for a free tour. The History and Collections of the MHS is a 90-minute docent-led walk through the public spaces here at the Society and provides some background on the art, history, collections, and architecture of the MHS. The tour is free and open to the public. Larger parties (8 or more), please contact Curator of Art Anne Bentley in advance at 617-646-0508 or abentley@masshist.org. While you’re here you will also have the opportunity to view our current exhibition, “God Save the People!” which explores events leading up to the American Revolution.

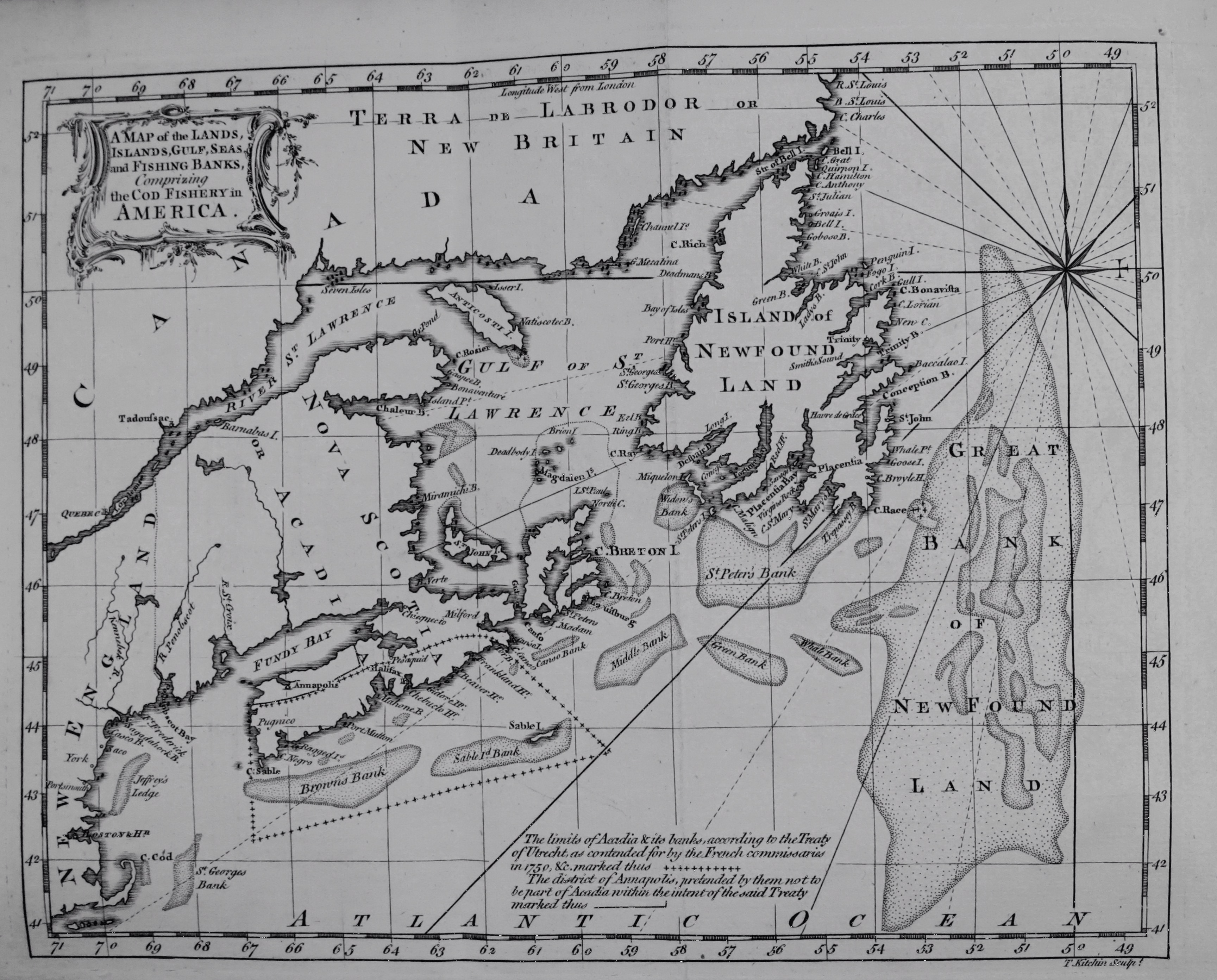

By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

Boundaries on land are largely man-made. These lines scribbled on paper or enclosed by transient fences signify what is claimed. Borders change over time. Geography shifts with natural disaster into or out of the ocean. Land boundaries are surprisingly fluid but not as immaterial as the open ocean, which poses the indeterminate question: Who owns the sea? Who has the right to fish the ocean?

In a four-post blog series, I aim to examine the claims over the North Atlantic fishery from 1764 to 1910. I cannot identify who owns the ocean. You may want to ask Poseidon or Neptune. My goal is to tell the story of claims and contestation of this “American fishery” between Great Britain, Canada, and the United States through our collections at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The contestation truly begins with the coming of the American Revolution.

In the North Atlantic, various claims to the plentiful fishing waters off the Newfoundland coast to the tip of Cape Cod in Massachusetts Bay caused great strife between Great Britain and its colonies. Great Britain’s economy relied heavily on Atlantic fish trade especially that of dried, salted cod. The growth in population and life expectancy in New England throughout the 18th century also increased the numbers of New England fishermen and their fishing vessels, and thus increased Atlantic fishing. In response to this additional competition in the Atlantic, British fish merchants cornered the market by prevailing upon Parliament to protect their interests in the “American” fishery. To this end, Sir Hugh Palliser became Governor and Commander-in-Chief at Newfoundland in 1764 and intensified the removal of New England fishing vessels from the coastal waters in support of a British fishery in the North Atlantic.

Massachusetts resident William Bollan published a treatise entitled The Ancient Right of the English Nation to the American Fishery in the same year as Palliser’s appointment. This publication summarizes a history of naval conflict in the North Atlantic in an effort to persuade his London audience of their might over the pitiable French. In establishing the English right to this fishery, he then asks to share these waters with the enemy:

“…I cannot forbear recolleƈting that the eagles grief was encreased on her finding that she was shot with an arrow feathered from her own wing; and that my cordial wishes for the future happy fortunes of my prince and country are accompanied with concern that after obtaining so many important victories, whereby the enemy was so far enfeebled and disarmed, and the sources of her commence and naval strength brought into our possession, there should be prevailing reasons for putting into her hands so large a portion of this great fountain of maritime power.”

Bollan’s use of the eagle shot with an arrow feathered from her own wing in hindsight unintentionally reflects the growing revolutionary sentiments in the British North American colonies during the 1760s.

With tensions rising over the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765, British seizures of American fishing vessels in Newfoundland waters increased the building momentum of riotous debate over colonial rights. In the summer of 1766, Captain Hamilton of HMS Merlin boarded the colonial schooner Hawke and demanded to know what business skipper Jonathan Millet had in the Newfoundland waters. The New England fishermen were there for cod fishing. Upon the response, the captain promptly seized the vessel and fish, according to Jonathan Millet’s deposition from 13 September 1766, “…[Captain Hamilton] threatn’d that if he ever Catch’d any New England Men Fishing there again that he wou’d seize their Vefsells & Fish and Keep all the Men, beside inflicting severe Corporal Punishment on every man he took,….” Spurred by his foul treatment at the hand of the captain, skipper Millet recounted his impressment grievances to the Justices of the Peace Benjamin Pickman and Joseph Bowditch in Salem for this deposition.

A plethora of impressment grievances appear in the 1760s in the MHS collections. In fact, William Bollan personally knew of impressment as a major issue of contention. Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson wrote to Bollan in the latter’s capacity as colonial agent in London on the issue of impressment in 1756. This letter was written a decade prior to the Hawke impressment. British inattention to colonial rights and the impressment of colonial fishermen certainly led to rebellion. But the contestation over Newfoundland fishing rights continued well into the 19th century.

In the next blog post, I will examine the fishing in the Early Republic as New England fishermen become citizens of the United States, and Britain’s continued impressment until the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.