By Dan Hinchen

Two things that make creating these posts for the Beehive a little bit easier are visual images and convenient coincidence. I lucked out this time around in having both. The images below (except the photo-portraits) were created by two men who seem to have very little to do with one another. One was a Civil War captain and later a librarian, while the other made a career for himself as one of the most prominent American artists of the late-19th and early-20th centuries. The first was an amateur who mainly did pencil drawings in his scrapbooks and journals, the second designed posters, catalogs, and held public exhibitions in major cities.

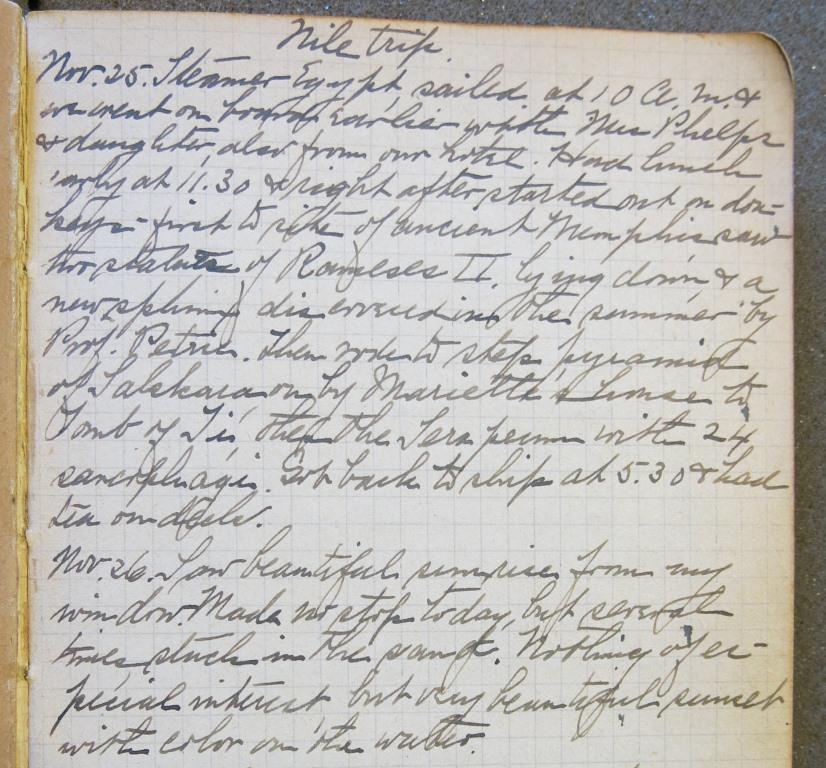

Eben W. Fiske (1823-1900) served during the Civil War as a Captain in the 13th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in Virginia. As part of the Fiske family papers here at the MHS, we hold several of his small notebooks which contain clippings from newspapers and a variety of pencil drawings. For ease of description, I split his drawings into two very broad categories: Civil War drawings and Other.

Fiske’s war artwork illustrates sketches of specific subjects such as the people and animals he encountered. I first saw his illustration pictured above in one of the Society’s past exhibitions. The image of this infantryman inspired me to further investigate Fiske’s artwork for this blog post.

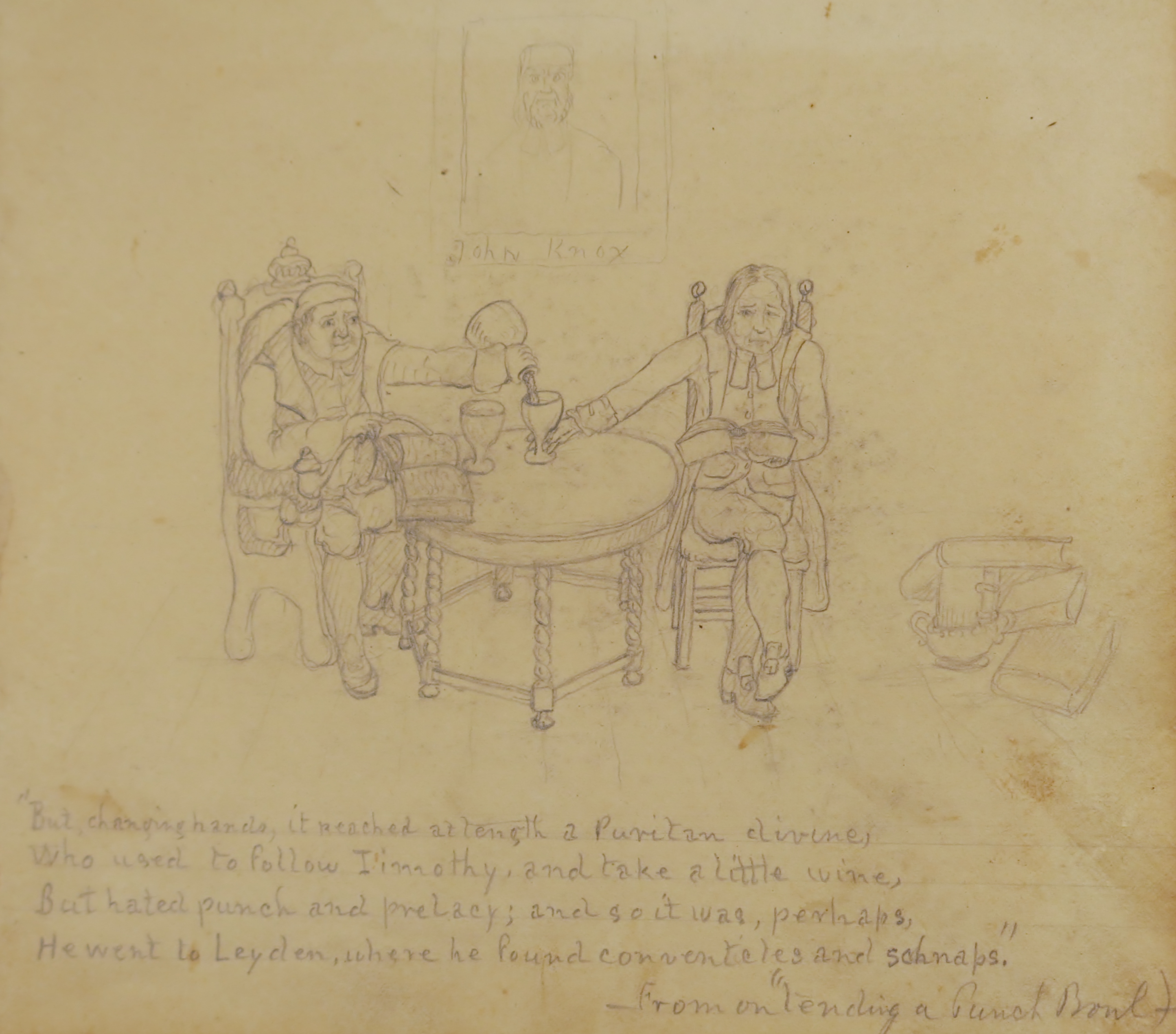

The set of drawings I describe loosely as Other, consists of illustrations that Fiske created to go along with verses from poems and other writings. This set of drawings reminds me somewhat of those done by Christopher Pearse Cranch, subject of a previous post here. One such drawing illustrates a single verse from the poem “On Lending a Punch Bowl,” by Oliver Wendell Holmes:

“But changing hands, it reached at length a Puritan divine/Who used to follow Timothy and take a little wine/But hated punch and prelacy; and so it was, perhaps/He went to Leyden, where he found conventicles and schnaps.”

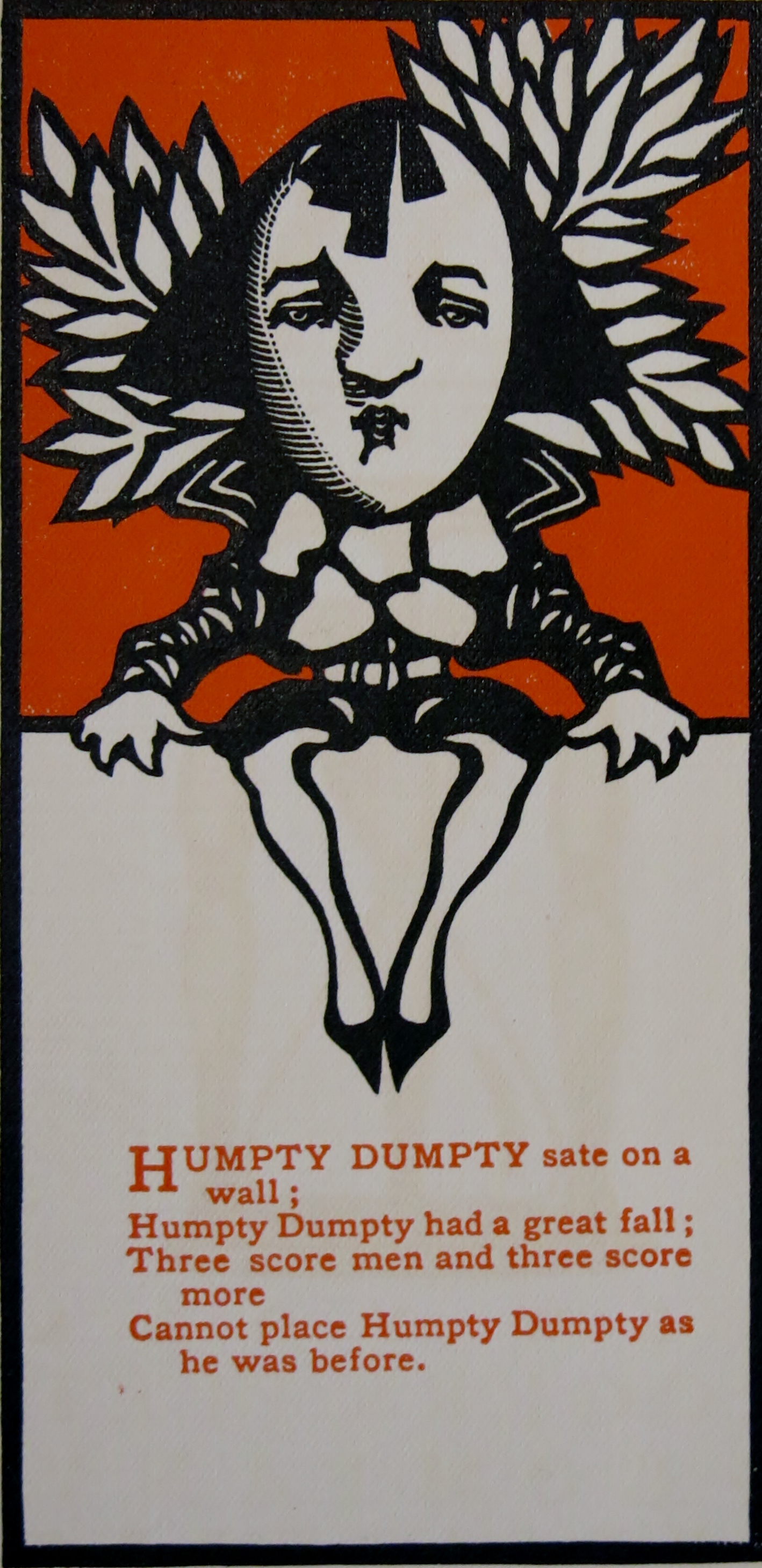

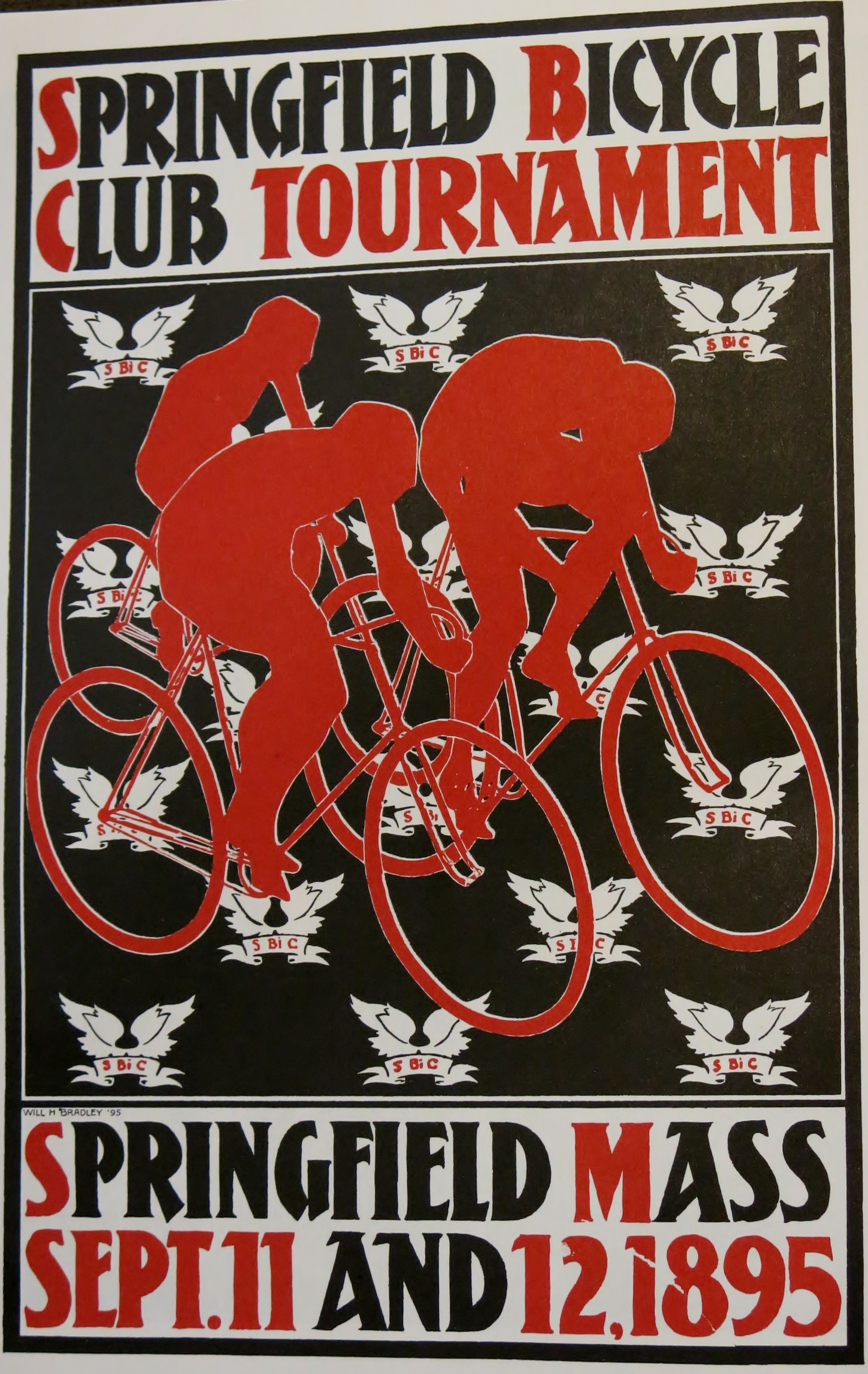

The second artist, Boston native Will H. Bradley (1868-1962), is best remembered as the “Dean of American Design.” Bradley’s Art Nouveau style widely graced the pages of commercial trade catalogs, posters, and public exhibitions through the late-19th and early-20th centuries. His career as a visual artist brought him international acclaim. He reigned in his time as the most highly-paid American artist. Recently, the MHS digtized a sample of his work for view on our website. Bradley designed and illustrated the Overland Wheel Co./Victor Bicycle catalog in 1899. Check it out here to learn more about his life and work.

In addition to the bicycle catalog available on the website, take a look at a few other pieces in the MHS collections that show Bradley’s work.

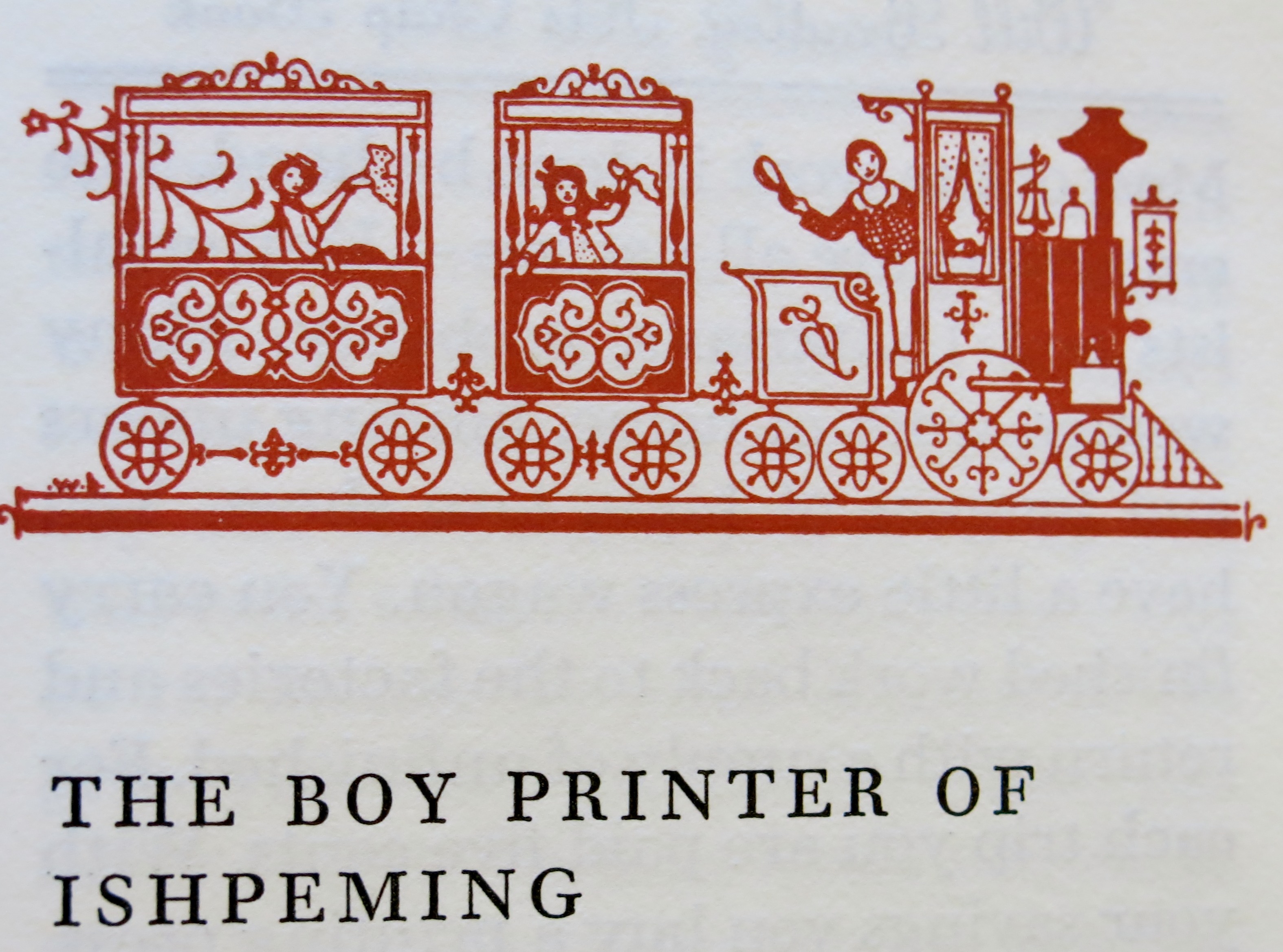

So, why is it that I am connecting these two men in this post? A clue lies in the image just above of the train. Fiske served as the librarian in Ishpeming, MI, a small town on the Upper Peninsula. Bradley, after the death of his father, moved with his mother to the town of Ishpeming, MI, to be closer to their relatives. It was here that he became a printer’s apprentice, his first job in the field he would come to dominate in his lifetime. It was a happy accident that led me connect these two men for this post. Unfortunately, I could not find information about the timing of Fiske’s tenure as librarian in Ishpeming. Perhaps a young Mr. Bradley crossed paths with the older librarian at some point in Ishpeming. Convenient coincidence that they should both end up represented at the MHS.

To find out more about the collections that the Society holds relating to these two Ishpeming-ites, try searching in our online catalog, ABIGAIL.

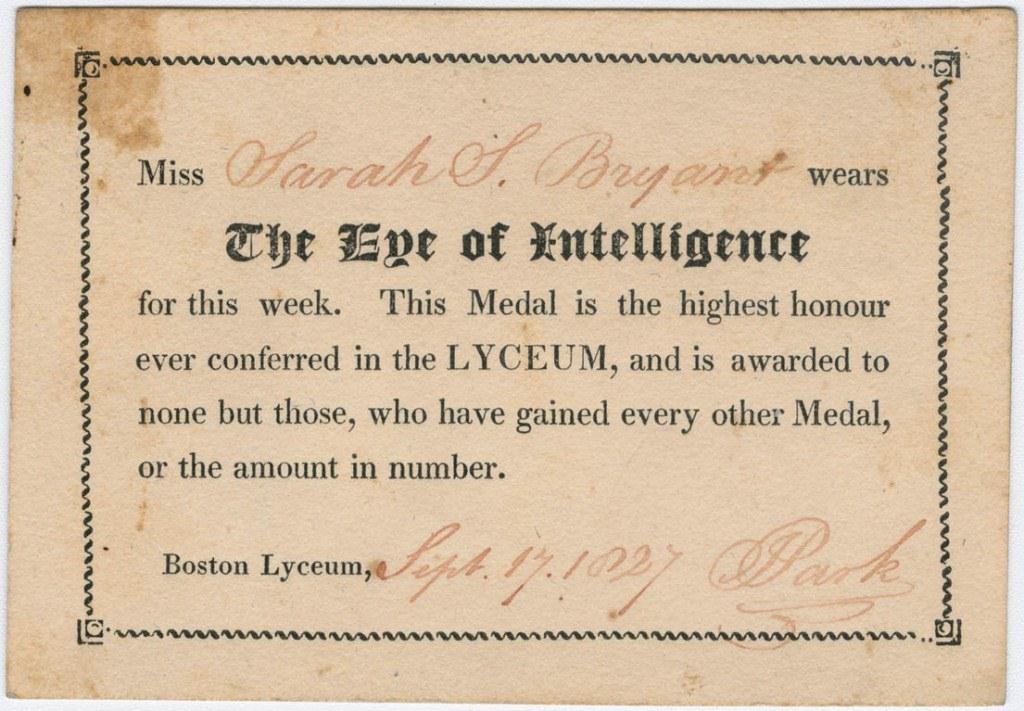

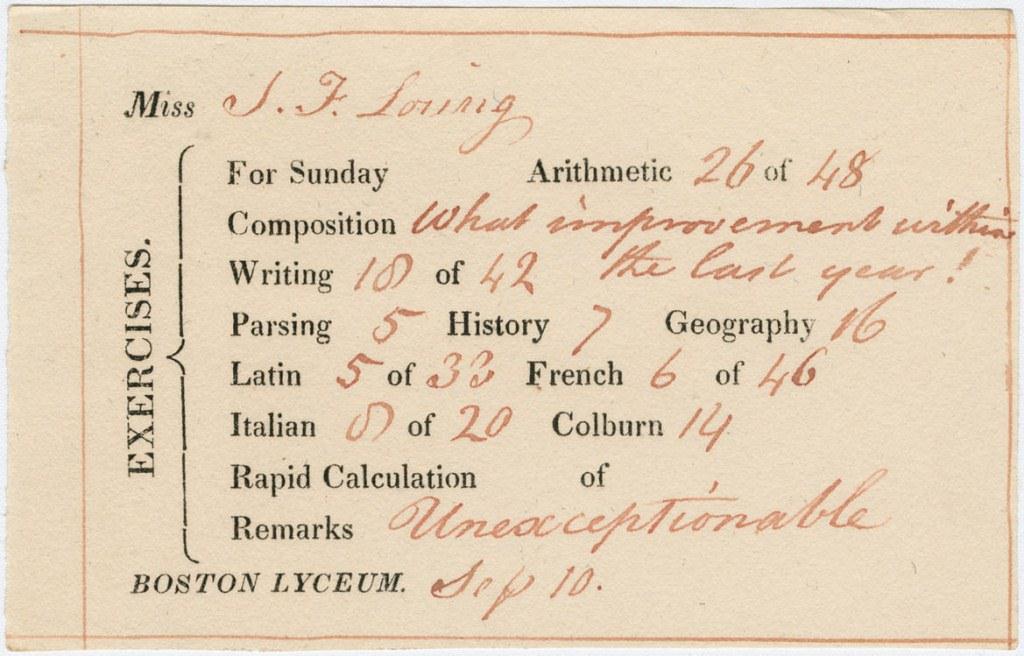

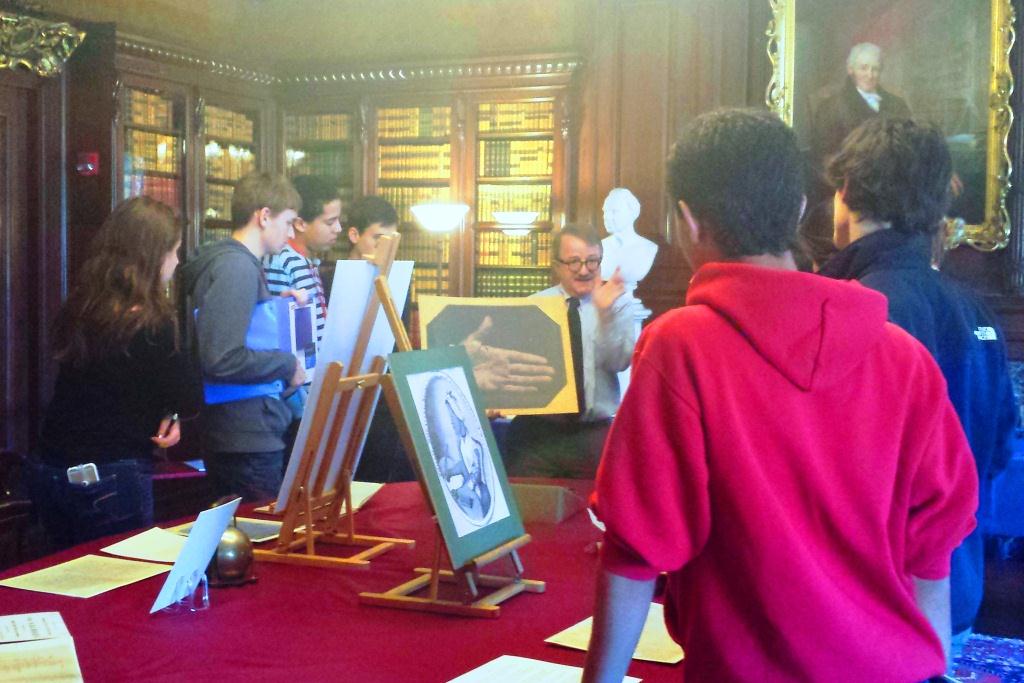

On November 10, students from Needham High School returned to the MHS for a program on the coming of the American Revolution in Boston. They analyzed propaganda from the 1760s and the 1770s, including this entertaining newspaper article encouraging colonists to

On November 10, students from Needham High School returned to the MHS for a program on the coming of the American Revolution in Boston. They analyzed propaganda from the 1760s and the 1770s, including this entertaining newspaper article encouraging colonists to  and the African Americans in the Civil War in order to help select topics for an upcoming project. Students then discussed the messages promoted in abolitionist propaganda such as

and the African Americans in the Civil War in order to help select topics for an upcoming project. Students then discussed the messages promoted in abolitionist propaganda such as