By Kittle Evenson, Reader Services

For my inaugural Beehive post I delved into the world of female incarceration, attempting to better understand the creation of women’s prisons in Massachusetts, and the codified societal controls imposed on women in the 19th century.

In 1874, Emory Washburn published “Reasons for a Separate State Prison for Women” and with impassioned rhetoric, called out the systemic inequalities leading to women’s imprisonment, and called for a shift in focus from punishment to reformation.

While I initially read his publication expecting a paternalistic discourse, what I found was a sharp commentary on women’s power for self-determination and democratic participation.

But for what we are bound to suppose wise reasons, the voice of only one sex can be heard at the ballot-box, while the other must content themselves with humbly making known their wishes to the legislature, that something may be done to relieve the Commonwealth from this inequality in the administration of justice in the case of the two sexes. It is not overlooked, that not a few of those who would be the inmates of such a prison as is here advocated, have become so from causes with which those whose votes help to settle questions of this kind have had much to do [emphasis added].

Crime is a form of social action; the criminal justice system a type of social control; and the arc of women’s history is inexorably linked to both. In puritan New England, women were predominantly brought up on charges of fornication and adultery, and even crimes such as murder, were often the result of secretive abortions, or desperate acts of infanticide. Punishment was evocative and public. As concrete expressions of social control, it served dual purposes as both a lesson to the female perpetrators and an establishment of boundaries for the women waiting in the wings.

Within our collections, there is a smattering of “last words” of colonial-era women convicted and punished for felonious crimes. Secondary sources, such as N.E.H. Hull’s Female Felons: Women and Serious Crime in Colonial Massachusetts deftly explicate the female experience in colonial courts, but women’s first-hand accounts of the 19th century justice system prove maddeningly elusive.

In his call for sex-segregated prisons, Washburn is speaking to a society in which women are jailed in the same institutions as men, yet offered no means with which to train or educate themselves.

Reformers saw the harsh conditions of men’s prisons as hardening and detrimental to women, with the lack of educational and vocational trainings failing to prepare them for a productive life beyond their incarceration. With no prospects independent of crime, recidivism among women was high, and the cycle of crime in the mid-19th century rarely broken. By advocating for separate women’s reformatories, Washburn saw a chance to break women free from this cycle. So long as the women had sufficient time to internalize the reform.

The process of working to reform in such prisons must, at best, be slow, and the attempt to do it in the period of a few months practically hopeless. Such sentences have reference to disposing of bad subjects for the time being, and not to the reforming of them (6).

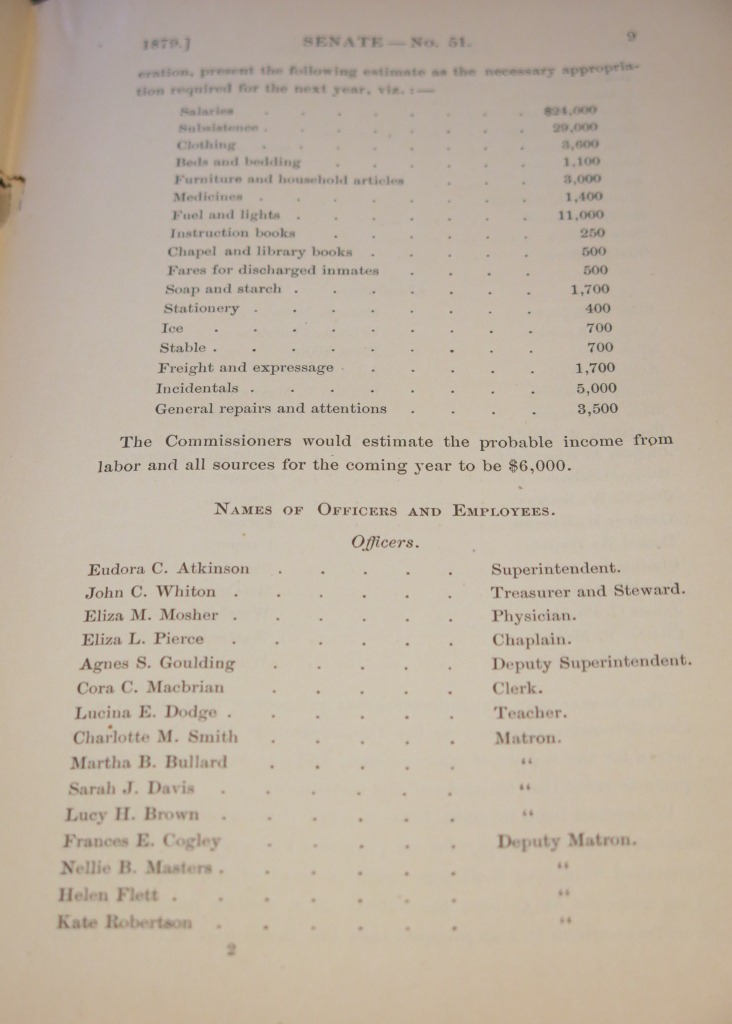

To better understand the women’s prisons that arose from this movement, I found the 1888 report to the Massachusetts Commissioners of Prisons detailing the first year of the Reformatory Prison for Women at Sherborn. The report echoes Washburn’s call for longer sentences and the necessity for access to education and vocational training. But it also complicates our understanding of female incarceration – detailing the all-female prison staff tasked with monitoring, controlling, and reforming the women under their care. This staff included a chaplain: Eliza L. Pierce, a physician: Eliza M. Mosher, and superintendent: Eudora C. Atkinson.

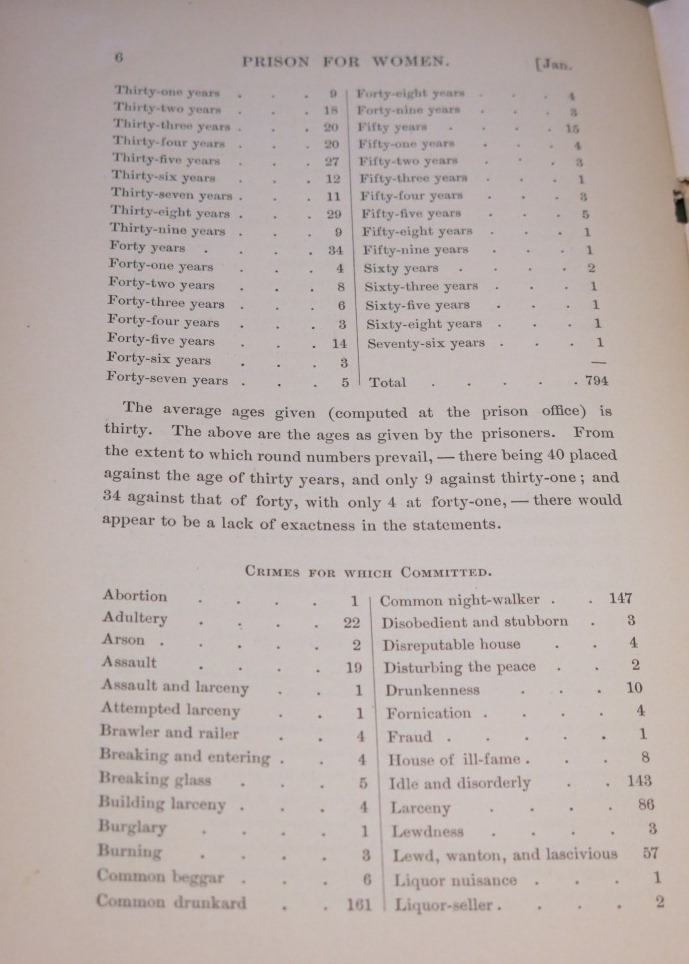

In its first year the prison held 794 women. 143 of the inmates were sentenced for acting “idle and disorderly”; 147 for being a “common night-walker”; and the most, 161, for being a “common drunkard” (161). While the women’s financial backgrounds are unclear, it was recorded that the majority, 54%, were foreign born.

Fom this tableau of sources, we see the beginnings of a rich context into which the experiences of women as gatekeepers, educators, protectors and prisoners can be woven. Questions abound as to the concrete changes these women pursued; the dynamics between domestic and foreign-born inmates; and the support these prisoners received after their release, specifically from institutions such as Temporary Asylum for Discharged Female Prisoners.

These are just a selection of the MHS’s offerings pertaining to women’s incarceration. Researchers interested in engaging further with these sources, or our broader manuscript and print collections, are encouraged to contact the library or stop by for a visit.