By Olivia Mandica-Hart, Library Assistant

Like many New Englanders, I followed the recent Market Basket labor strike with near-obsessive interest. Of course, a small, selfish part of me was irked that my “More for Your Dollar” shopping had been temporarily suspended. But beyond that, I was inspired by the employees’ bravery and revolutionary spirit. After weeks of negotiations and uncertainty, I was pleasantly surprised that the workers had triumphed over the CEOs. I’d noticed two important things while following the story; first, that many of the employees who were protesting “on the front lines,” as well as the consumer advocates who boycotted the store, were women. And secondly, that in the news media, many labor activists discussed the “record breaking” strike as distinctly unique to Massachusetts. These two facts are not particularly startling, given the state’s strong history of labor organizing and activism, much of which began with Massachusetts women.

In the 1830s, more than fifty years before labor movements became popular throughout the United States, the Lowell Mill women began organizing and striking, forming the first union of female workers in the United States. Over the next few decades, the same radical spirit picked up momentum and moved to the city of Boston.

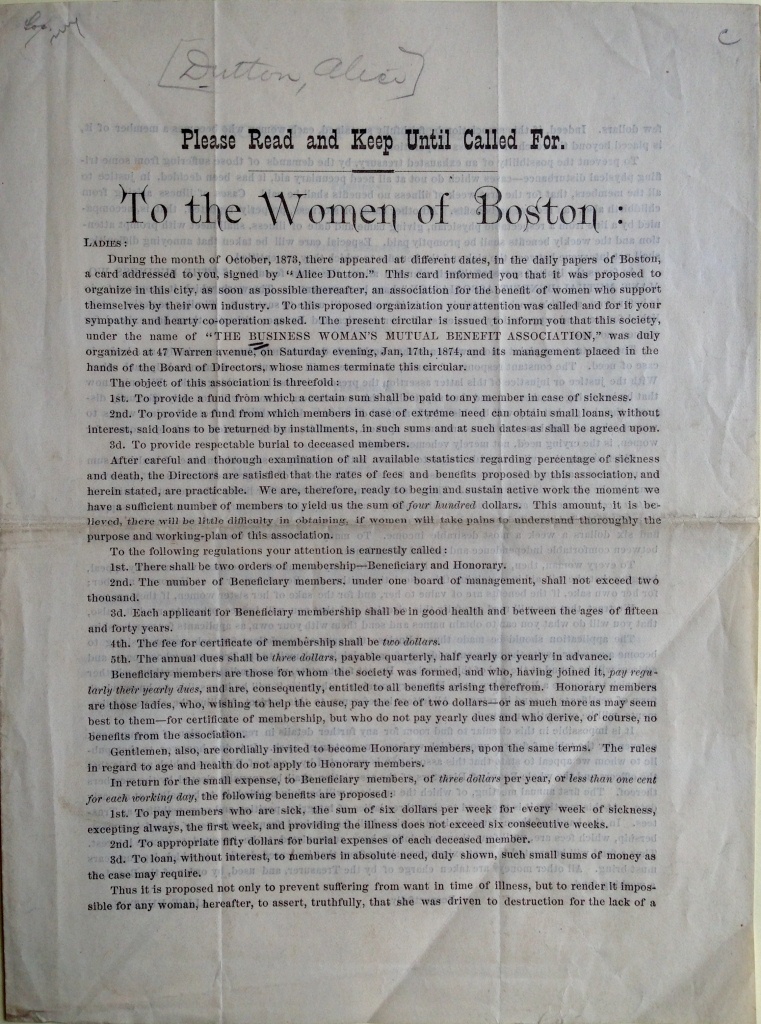

In 1874, forty-six years before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, a group of female business owners in Boston formed the Business Woman’s Mutual Benefit Association, which published circulars in Boston newspapers to advertise its services.

This circular, dated 27 February 1874, explains that “the object of [the] association [was] threefold:”

1st. To provide a fund from which a certain sum shall be paid to any member in case of sickness.

2nd. To provide a fund from which members in case of extreme need can obtain small loans, without interest, said loans to be returned by installments, in such sums and at such rates as shall be agreed upon.

3d. To provide respectable burial to deceased members.

To include as many people as possible, the Association established two tiers of membership: beneficiary members paid yearly dues and were subsequently entitled to all of the aforementioned benefits. Honorary members paid a one-time fee and received a certificate, but did not gain any benefits from the association. Men were “cordially invited to become Honorary members,” but the Board of Directors was comprised entirely of women.

Although women’s rights were not supported by the majority of Bostonians, the Association did have some allies. For instance, in its 2 April 1874 issue, The Index: A Weekly Newspaper Devoted to Free Religion, introduced the Association’s statement by writing:

We have been requested…to give a ‘word of notice’ to the following circular; but we find it so excellent that it seems proper to publish it in full in THE INDEX, with our heartiest approval of the organization and its object. Similar ones ought to be everywhere established; and the attention of all friends of the cause of women is called to one of the best plans yet devised to further it.

Nineteenth-century society provided independent women with very few legal and social rights, so these Bostonian businesswomen decided to organize and unite to protect themselves (and each other). Their circular states:

The constant complaint among women is that nothing is done to help them, pecuniarily, as a body, in case of need. The constant response of men is, that women will not unite as do men to help each other…by becoming members of, and thus supporting this association, women will not only effectually disprove the charge, but they will by this simple method do more to defeat the evil effects of unjust wages to women…

This last point seems particularly poignant and timely given that in mid-September, the United States Senate yet again blocked the passage of the Paycheck Fairness Act, a bill that would have strengthened equal pay protections for women. Despite the valiant efforts of these pioneering ladies, women are still fighting to be paid equal wages, one hundred and forty years later. Perhaps we should look to these revolutionary nineteenth-century women for some twenty-first-century inspiration in our continued fight for gender equality.