By Dan Hinchen

The last two times I wrote for the Beehive (here and here) I spoke about the important interplay that goes on between the library staff and researchers. In both cases this interplay revolved around the parties sharing information about and exploring collections relevant to a particular topic. Recently, though, one of our regular researchers casually asked me whether I saw a collection of sketches and drawings with which he was working. Since I did not see them before, prior to returning the material to the stacks I decided to have a peek.

The first thing that I saw was a drawing I recognized immediately and which I remember seeing in a textbook in high school, showing an eyeball raised on long, spindly legs and wearing a top hat, striding through an unembellished countryside. The “transparent eyeball,” a facetious illustration of Ralph Waldo Emerson remains a popular image.

Christopher Pearse Cranch was a transcendentalist artist and poet. Born in 1813 in what is now Alexandria, VA, he eventually made his way to Boston to study divinity at Harvard in 1835. Though Cranch was never ordained, he served for a time as a missionary in New England and the Midwest. While at Harvard he became associated with the New England Transcendentalists. Through his life, Cranch published several volumes of poetry, served as an editor and contributor for James Freeman Clarke’s Western Messenger, wrote frequently for various periodicals, published a pair of children’s books, and did a blank verse translation of Virgil’s Aeneid. Despite all of this, it is his drawings for which he is most remembered, most of which were not published until they were rediscovered by F. DeWolfe Miller in 1951.

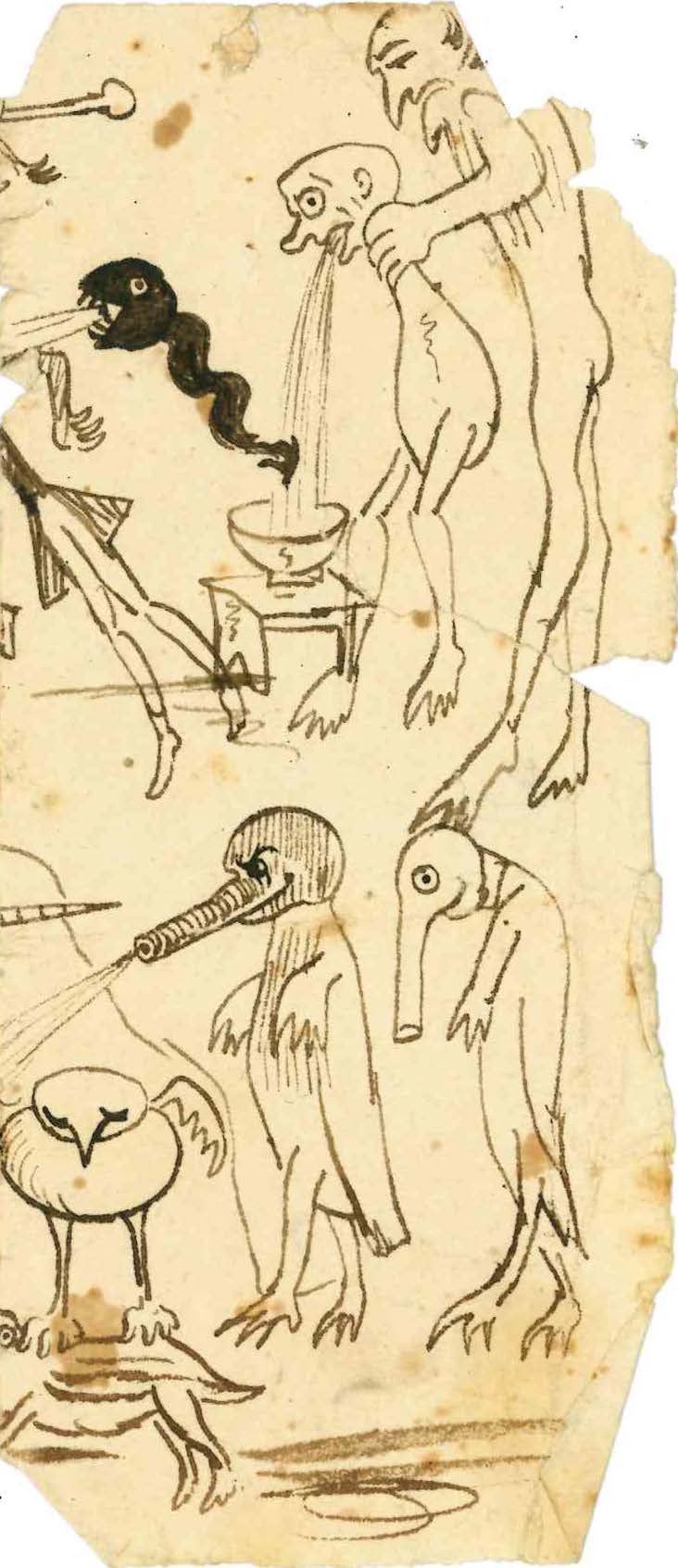

What struck me first as I looked through the drawings was how much his sketches called to mind images from other artists from very disparate times and places. The first thing conjured up by some of these drawings are the works of the 15th-16th century Dutch painter, Hieronymous Bosch, especially his famous triptych “The Last Judgement.”

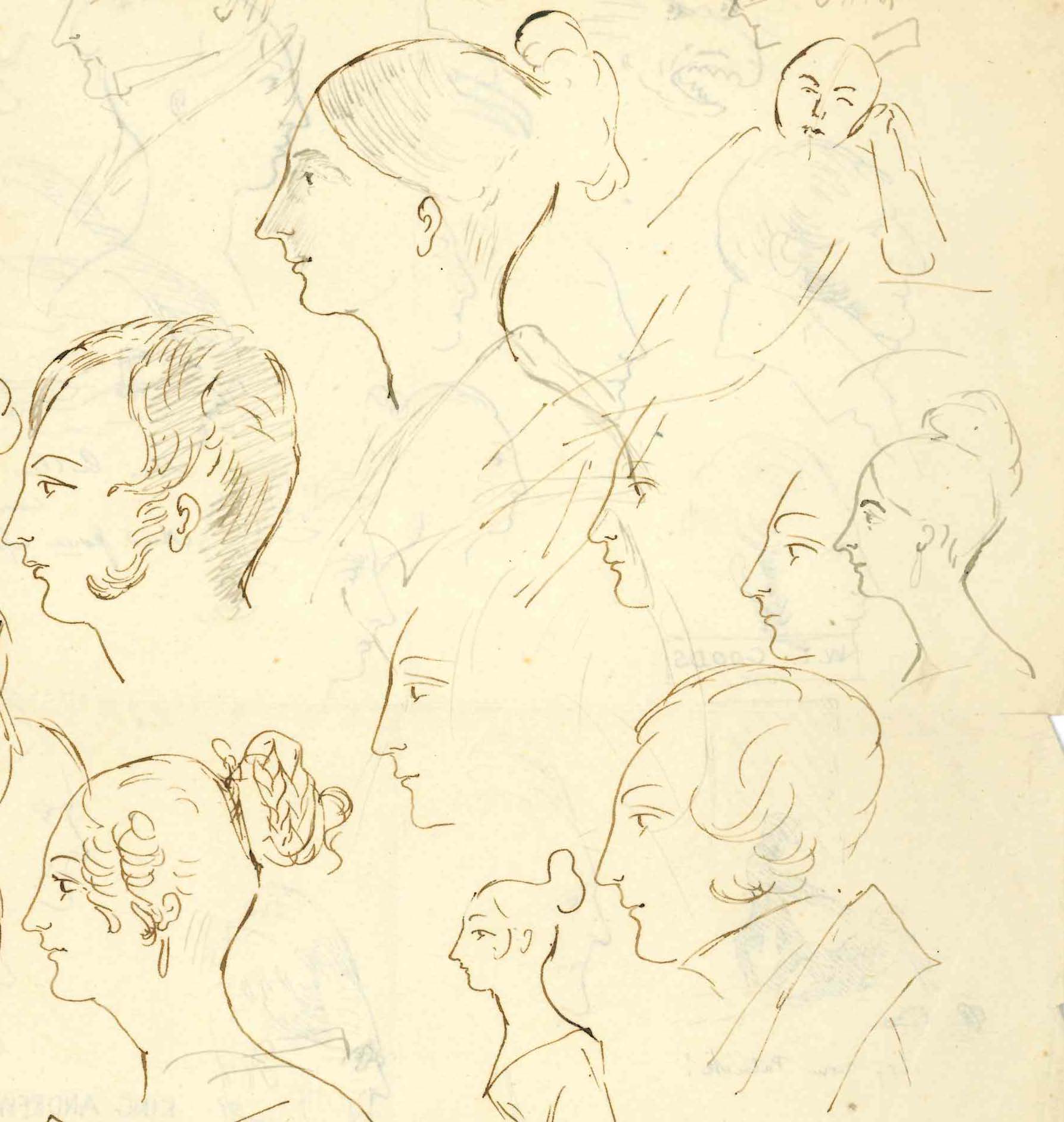

Beyond this first impression I was intrigued by the breadth of styles that Cranch employed and delighted in the strange doodles he created. Some of them are funny and slightly satirical, others are repetitive depictions of people in profile. Many of these profiles, as well as some other creatures he drew, remind my very much of the style employed in the Beatles’ animated movie Yellow Submarine, especially the Victorian-esque profiles:

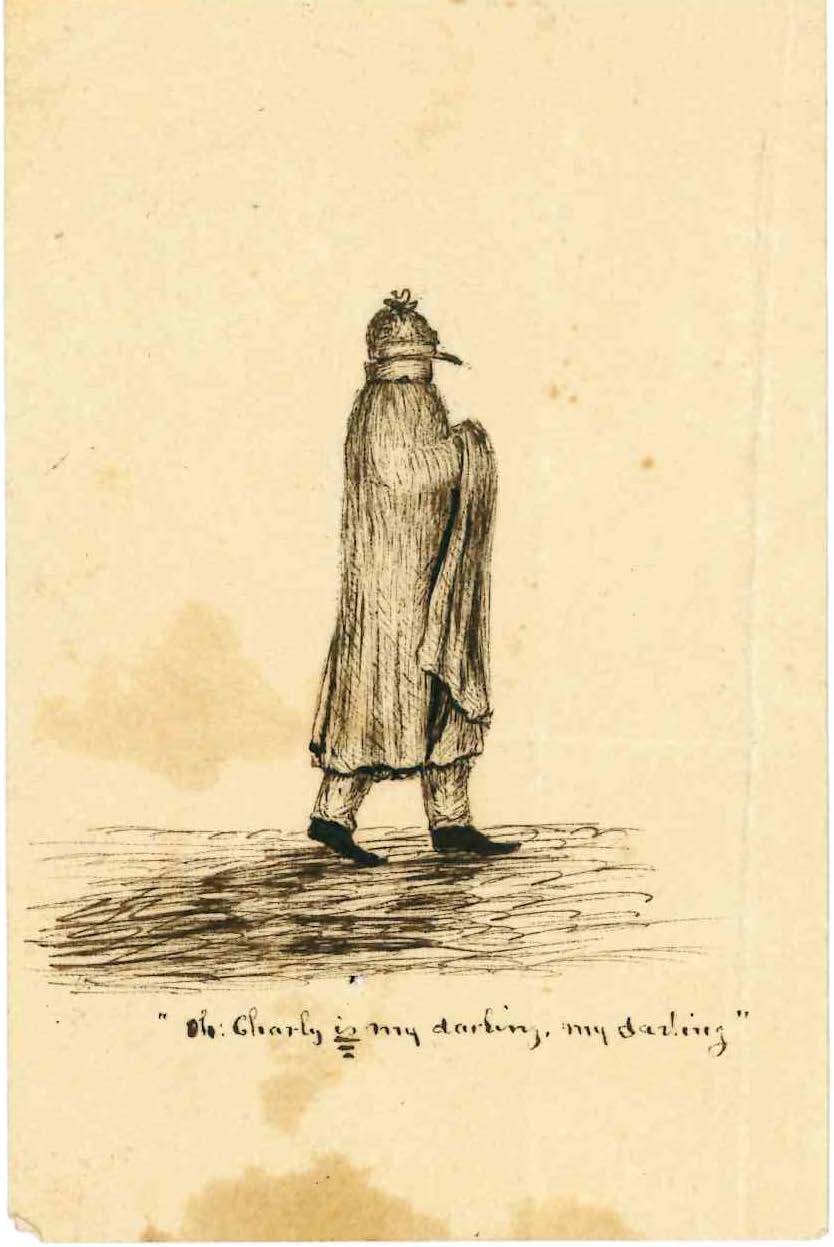

Another image I found, depicting a cloaked and somewhat shadowy figure, looks like it would be right at home in a collection of drawings by the Massachusetts illustrator Edward Gorey:

“Oh: Charly is my darling, my darling.”

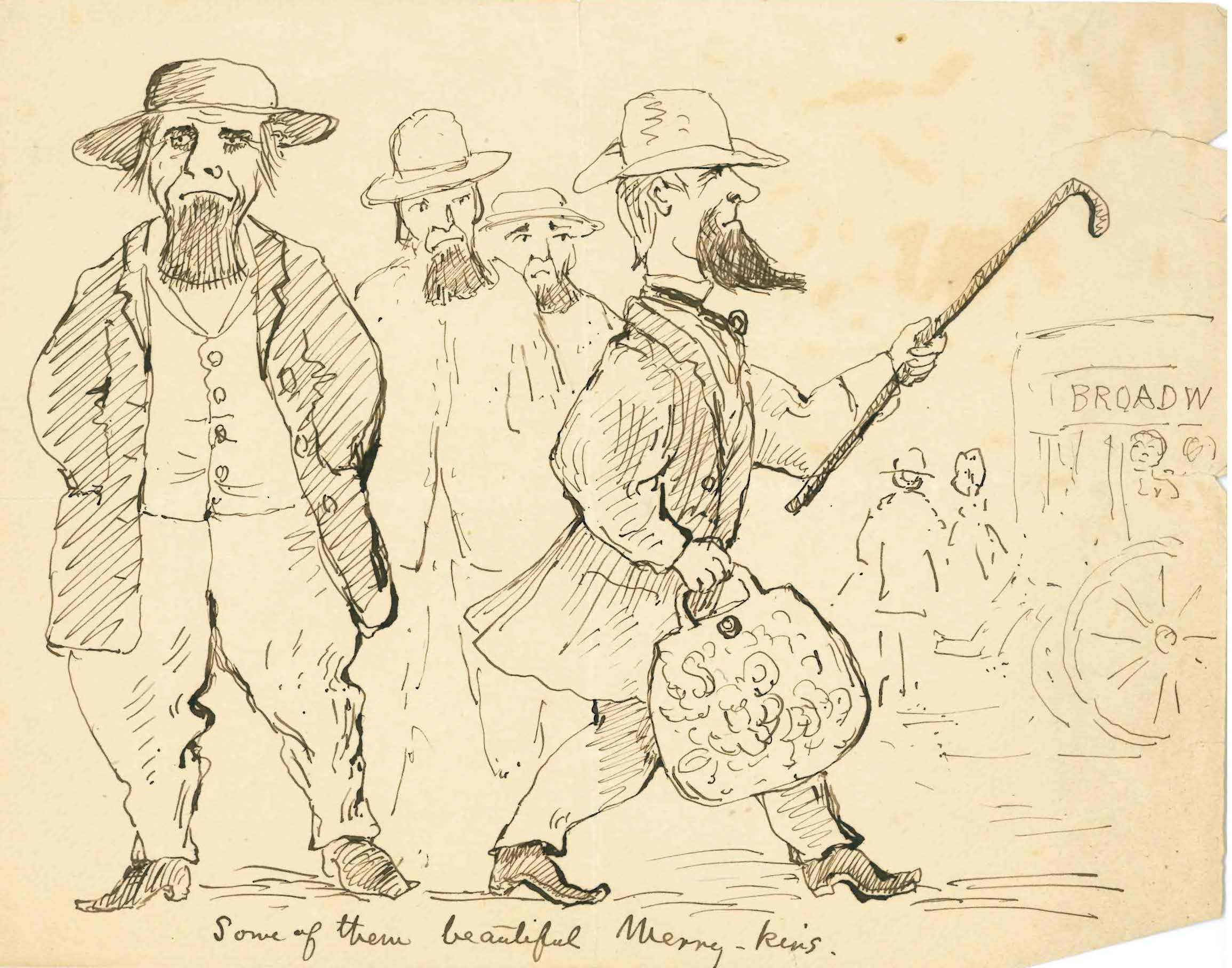

Also present were little pieces of satire, sometimes aimed at specific people or situations, and some, like this one, aimed at Americans in general:

“Some of them beautiful Merry-kins.”

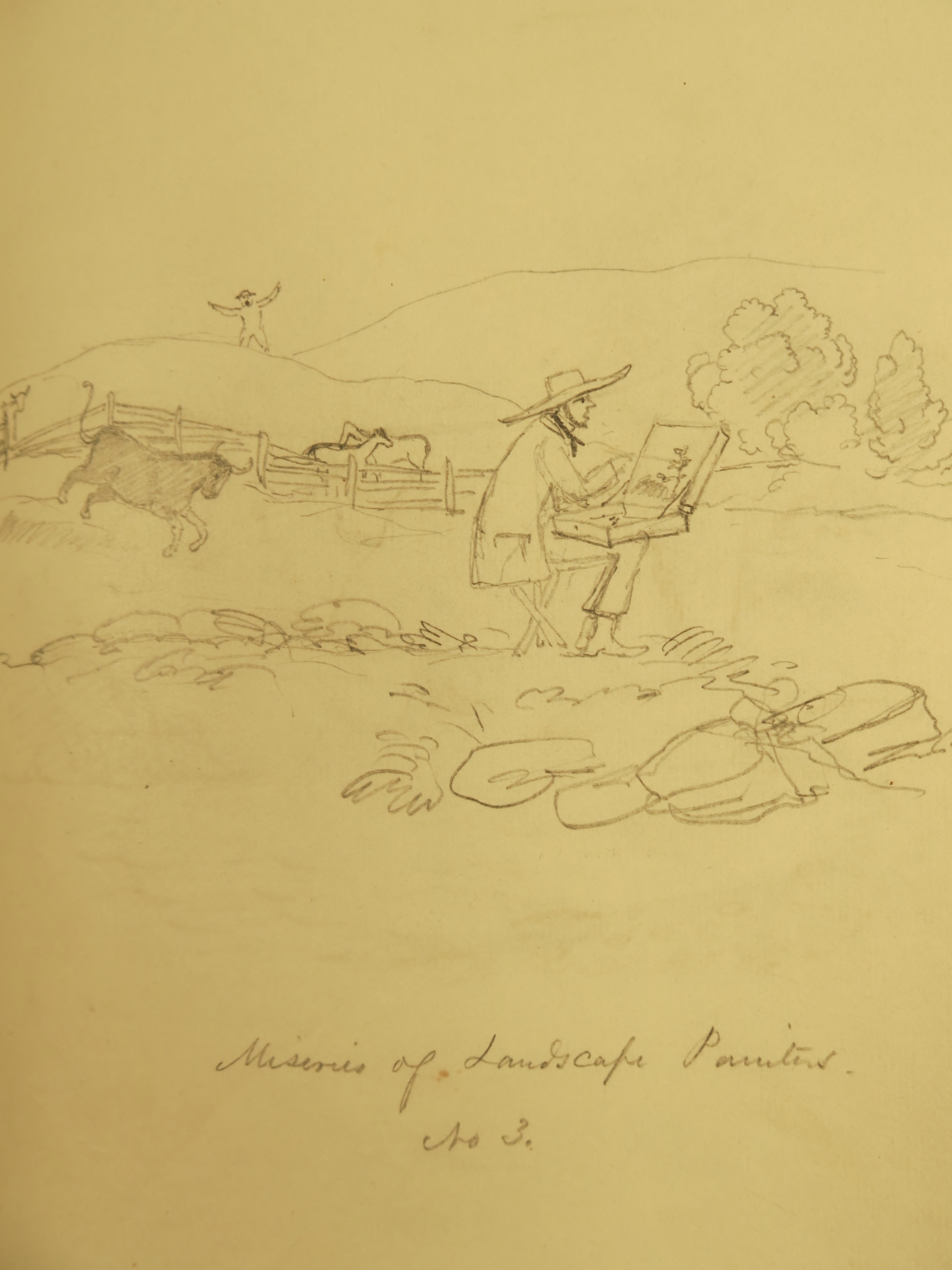

In addition the types of images you see here, Cranch also did some serialized cartoons that followed themes. One series of drawings was made up of imaginitive illustrations of lines from various works of Shakespeare. Another series of several images showed the “Miseries of Landscape Painters.”

“Miseries of Landscape Painters.

No 3.”

Despite all of the whimsy present in many of Cranch’s drawings, and despite the “misery” of the form, he also showed talent with landscape images:

While Cranch’s drawings are nothing new to many people, without a casual interaction with one of our researchers I might never have seen them in this way. This is just one more example of how important and how beneficial it is for us as librarians to interact with our researchers. What do you think about Cranch’s drawing?

Sources:

– Christopher P. Cranch drawings [graphic]

– Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds. 1999. American National Biography. New York: Oxford Univeristy Press.