By Susan Martin

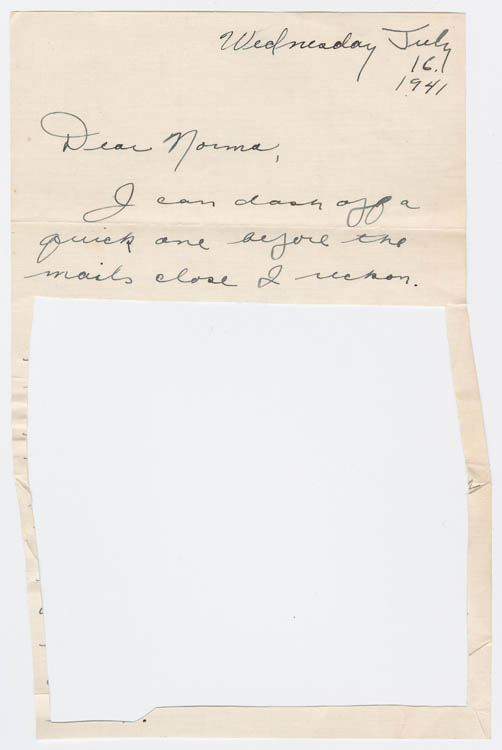

The MHS recently acquired a small collection of Norma A. Krtil papers that includes nine World War II letters from Krtil’s boyfriend, 23-year-old Donald K. Kibbe of Westfield, Mass. Sgt. Kibbe was an American volunteer with the Royal Canadian Air Force serving in England. Unfortunately, some of his letters arrived in Westfield looking like this:

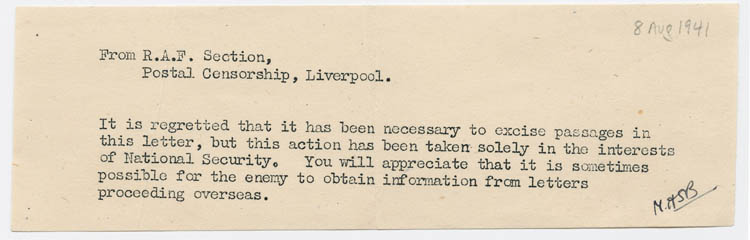

Now, I’ve seen a number of wartime letters with censorship marks or redacted passages, but this is definitely the most zealous censorship I’ve come across. Obviously these particular passages were (literally!) excised because they revealed Kibbe’s location and information about specific equipment and missions. In fact, the R.A.F. censor enclosed this helpful note in one of the envelopes:

The content of Kibbe’s correspondence—what’s left of it—is also interesting. For example, in his first letter after shipping out, he wrote to his girlfriend with disappointment:

Norma, I lost your pin. I ransacked the house for it the morning before leaving but it was such a small thing & the house is so big. They’re going to send it to me if they find it. I feel terribly bad about it. I wanted something you wore and held in your hands and gave to me with your hands and I had it & then I lost it. But if I’ve lost the pin I’ll never lose the memory of you nor the memory of the words you said the night you gave it to me. Norma, just love me half as much as I love you.

Happily this wonderful passage remains intact. (By the way, Kibbe later found the pin and wore it “inside [his] pocket beneath the wings.”) But Kibbe’s story, like so many others, ended tragically. He was killed on 30 Sep. 1941 in a plane crash on the Yorkshire moors. He had been serving as second pilot on a bombing raid to Stettin, and the plane went down on its return flight. It was his first mission.

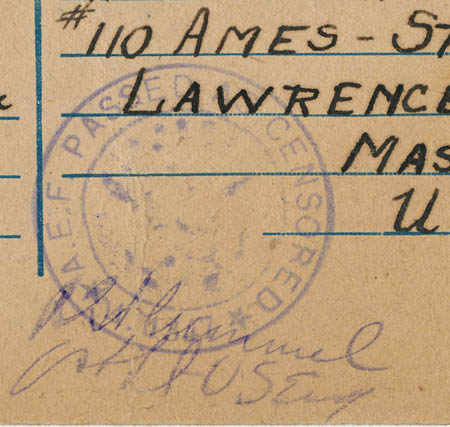

Of course, censorship of wartime letters was nothing new. Letters written by soldiers during World War I also had to be approved by censors, and it’s not uncommon to see marks or stamps on them, like these on the letters of Alton A. Lawrence and William F. Wolohan, both from 1918:

But young men, far away from home, placed in frightening situations, and desperate to reach out to their families and friends, often balked at the restrictions. When he arrived in Europe with the American Expeditionary Forces, Wolohan complained:

All the fellows are asking each other what to write as this is about the first time their mail has been censored, and they are having a great time trying to send a decent letter. They have so much to say or would like to say and yet dont know just what they are allowed to write.

Pfc. Brooks Wright, a World War II cryptographer from Cambridge, Mass. serving in India in August 1943, told his family the story of a fellow serviceman’s frustration with the censorship.

You will be amused to hear of a letter which Calahan sent home. In it he complained of censorship in no complimentary terms. Between the lines was written “He’s not far from wrong –Censor.”

Wright himself didn’t suffer much at the hands of the censors, though he did have the occasional phrase or passage cut from his letters à la Kibbe, usually when he was describing something specific about his location. Even a printed program for a concert he attended, enclosed with a letter, was redacted: “The […] Symphony Orchestra.”

But Wright was fond of drawing and illustrated many of his letters with scenes from his environment, local architecture, etc. And while he was a careful letter-writer, his sketches revealed more. His botanical sketches were so detailed, in fact, that when his mother took them to Harvard’s Gray Herbarium, the experts there were able to identify the species and pinpoint precisely where her son had been posted.