By Peter Drummey

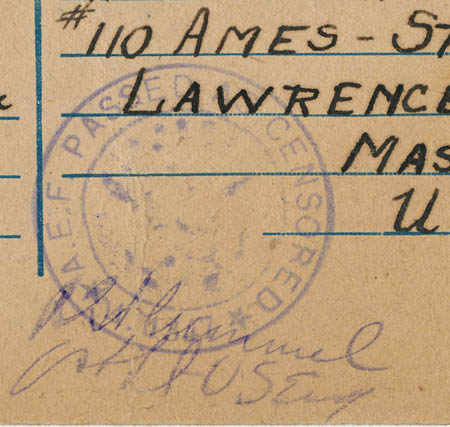

The release of the new George Clooney film, The Monuments Men, recalls a fascinating talk given at the Historical Society in December 1980, and published as “Remembrance of Things Past: The Protection and Preservation of Monuments, Works of Art, Libraries, and Archives during and after World War II” (Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 92, p.84-99). Our speaker was Mason Hammond, the Pope Professor of the Latin Language and Literature Emeritus at Harvard University. Professor Hammond, by then well into his seventies, was an enthusiastic member of the MHS (the man that the Adams Papers editors and other staff members turned to when a difficult Greek or Latin passage appeared in a manuscript), but until that day his fellow members probably saw him as a stereotypically tweedy academic historian. While his lecture was an overview of the quietly heroic effort of American and British curators, conservators, and art historians to save cultural treasures in wartime Europe, just enough of former Captain (later Lieutenant Colonel) Hammond’s own experiences enlivened his narrative to give his audience an inkling of the great adventure that he had participated in almost forty years before, and the remarkable role that he played as the first—and for a time the only—”Monuments Man.”

In his MHS talk, Mason Hammond described his path to a key role in the Allied preservation effort first in Sicily and Italy, and later in Northern Europe as almost accidental. In 1943, the director of the Metropolitan Museum in New York was appointed the first Fine Arts and Monuments Officer of the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories, but he was too fat to pass his physical, so Hammond, an intelligence officer at the Pentagon though not an art historian, was sent to North Africa in his place. Here Hammond was too diffident about his qualifications. He already had a lustrous career as a student and teacher at Harvard; had continued his studies of ancient art and archaeology at Oxford as a Rhodes scholar; and spent three years teaching at the American Academy in Rome. In Sicily and then on the Italian mainland, he developed the pattern for the rescue work that followed. Inadvertently, he also may have given the “Monuments Men” their name. His Boston accent proved so challenging for his British colleagues (who heard him say “fine arts and monuments” as “finance and monuments”) that for the sake of clarity, they reversed the order of words in the title of his section to “Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives”—and hence the “Monuments” rather than the “Fine Arts” (or “Finance”) Men.

Mason Hammond’s role in the Second World War is not unknown. He appears in recent popular histories by Robert M. Edsel with Bret Witter, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History (2009), and Saving Italy; The Race to Rescue a Nation’s Treasures from the Nazis (2013). If his own narrative is more measured than the breathless treasure hunt described in both books and the new film, it places the work of the Monuments Men in a larger context.

What would Mason Hammond have made of the new Monuments Men movie? We cannot really say, but in his talk he described the work of the monuments officers mostly in terms of architectural preservation and the restoration of museum and archival collections within their countries of origin, rather than the focus of the film—the hunt for art treasures looted from private collections in countries occupied by the Nazis. In fact, Hammond was extraordinarily fair minded in assigning responsibility for the accidental or deliberate destruction of architectural monuments and buildings, as well as the contents of museums and libraries. He thought that what he believed to be the worst cultural loss of the war, the destruction of the bulk of the collections of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, probably had been an accident rather than the result of Nazi malevolence or Russian revenge.

As a student of ancient history, Hammond probably was about the only person who could find a silver lining in the controversial Allied bombing of the Monastery of Monte Casino in Italy early in 1944 (this event is shown as leading to the creation of the Monuments Men in the new film, although Hammond had been in the field for almost nine months when the attack took place). As he noted, the Germans had removed the library of the Monastery to the Vatican before it was attacked. He thought the bombardment that followed had stripped away modern accretions to St. Benedict’s original structure, allowing its restoration in “a more suitable Romanesque style.”

Ironically, at the war’s end, Hammond found himself caught up in what appeared to be American-sponsored looting. He was serving in Berlin, the custodian of a bank vault filled with boxes labeled “Rembrandt” and “Rubens” that had been rescued from a phosphate mine in Thuringia. All the Monuments Men in Germany, regardless of rank (and by then Hammond was a senior officer in the detachment), signed a “most unmilitary” protest of a plan to remove works of art from Germany to the United Sates—a plan that the Monuments Men found too closely resembled the looting of cultural treasures by the Germans. While art works came to the United States and were stored at the National Gallery, in due course they were returned to Germany.

There is some presumption in claiming one of Harvard’s most faithful alumni and faculty members as the Society’s own “Monuments Man,” but Mason Hammond was an active member of the MHS for forty-four years, regularly attending MHS events until not long before his death in 2002, at the age of ninety-nine.

On 29 January, the Society hosted a special author talk for a very lucky group of middle-school students. The star of the show was none other than Cokie Roberts: MHS Fellow, journalist, political commentator, and author of the new children’s book Founding Mothers: Remembering the Ladies. The book, which is based on her 2004 bestseller Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation, chronicles the lives of the women who helped to found and nurture the United States. Abigail Adams is duly represented, as are Martha Washington, Phillis Wheatley, and Mercy Otis Warren. The book also introduces young readers to characters who might be less familiar: women like Deborah Sampson, the Massachusetts native who disguised herself as a man and fought in the Revolution, or Esther DeBerdt Reed, who raised more than $300,000 to purchase supplies for the underfunded Continental Army.

On 29 January, the Society hosted a special author talk for a very lucky group of middle-school students. The star of the show was none other than Cokie Roberts: MHS Fellow, journalist, political commentator, and author of the new children’s book Founding Mothers: Remembering the Ladies. The book, which is based on her 2004 bestseller Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation, chronicles the lives of the women who helped to found and nurture the United States. Abigail Adams is duly represented, as are Martha Washington, Phillis Wheatley, and Mercy Otis Warren. The book also introduces young readers to characters who might be less familiar: women like Deborah Sampson, the Massachusetts native who disguised herself as a man and fought in the Revolution, or Esther DeBerdt Reed, who raised more than $300,000 to purchase supplies for the underfunded Continental Army.