By Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

There’s been a lot of chatter recently about the new Netflix original series “Orange is the New Black,” a drama about life in a women’s prison. As Heather Chapman, one-time volunteer at the Massachusetts Correctional Institute in Framingham, writes in The Guardian:

The reality is over 2 million Americans are currently locked up. Put another way, that’s 1 in 100 US adults. And 1 in 37 Americans will be locked up at some point in their lifetimes. Despite the “lock ’em up and throw away the key” mentality, most of these people will re-enter society. The public should understand our correctional system – and its financial and human costs – far better than we do now.

What does a twenty-first century Internet series have to do with an institution like the Massachusetts Historical Society? While the medium is new, the message is not: American calls for prison reform and advocates of prisoner’s rights have long historical precedent. Before the advent of moving pictures – and long before the invention of the Internet – reformers and prison advocates alike used text and images, to convey their message. Here are a few examples drawn from the MHS collections.

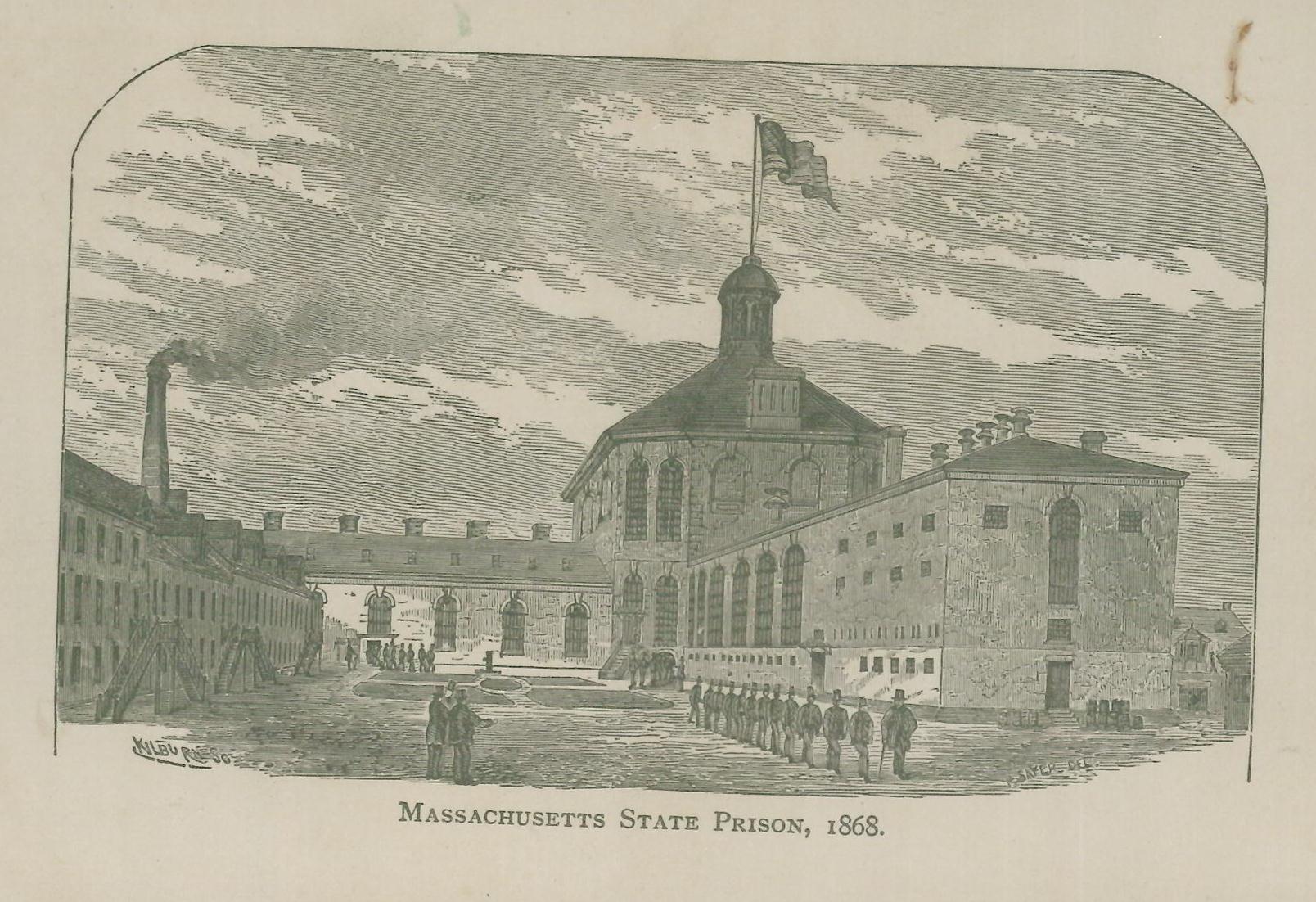

This illustration from prison warden Gideon Haynes’ Pictures From Prison Life: An Historical Sketch of the Massachusetts State Prison (1869) depicts a tidy building and grounds, with a row of prisoners exercising.

This illustration from prison warden Gideon Haynes’ Pictures From Prison Life: An Historical Sketch of the Massachusetts State Prison (1869) depicts a tidy building and grounds, with a row of prisoners exercising.

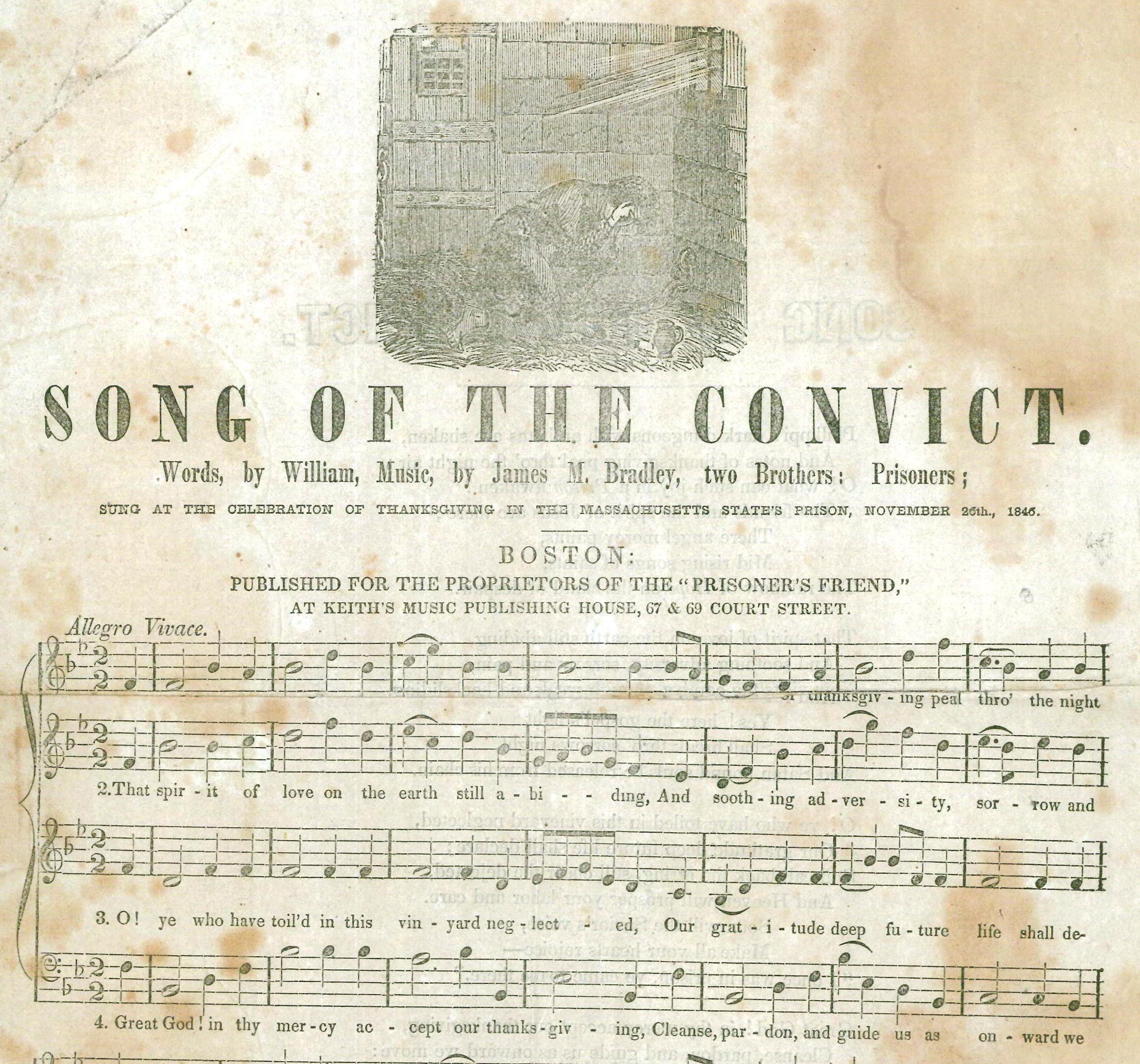

A different perspective can be found in the lyrics and illustration of “Song of the Convict,” a maudlin lament written by William and James Bradley, “two brothers, prisoners,” for the celebration of Thanksgiving at the Massachusetts State Prison in 1846. Along with the image of the forsaken prisoner kneeling in his cell, the lyrics of the song document the religious motivation of many behind prison reform campaigns during this period:

A different perspective can be found in the lyrics and illustration of “Song of the Convict,” a maudlin lament written by William and James Bradley, “two brothers, prisoners,” for the celebration of Thanksgiving at the Massachusetts State Prison in 1846. Along with the image of the forsaken prisoner kneeling in his cell, the lyrics of the song document the religious motivation of many behind prison reform campaigns during this period:

Phillippi’s dark dungeons with anthems are shaken,

And notes of thanksgiving peal thro’ the night air;

O! what can such joy in a Prison awaken?

The friends and the spirit of Jesus are there;

There angels mercy paints,

Mid rising songs of saints,

The rainbow of Hope on the cloud of despair.

Women in prison (the subject of “Orange is the New Black”) were then, as now, their own particular topic of concern. In a circular tentatively dated from 1849, the Prisoner’s Friend Association reported to its membership:

The design of the Charity is, to furnish to female prisoners, on their discharge from the House of Correction, a temporary home, to encourage them to reform, and to enable them to do so by procuring for them honest means of support.

Examples of successful “reform” and subsequent participation in society are detailed in explicitly gendered (and in one case racialized) terms:

One, who in the moment of temptation was guilty of theft … was returned to her family [upon release], where she has since, for a period of eighteen months, faithfully discharged her duties as a wife and mother.

A young girl, also, whose heart had not been hardened by crime, after a short imprisonment, was taken by our Agent and furnished with a place of service, where she remains.

A colored girl, with few acquaintances and no friends, was sent to a family in the country, where she has given such evidence of fidelity and capacity as to merit and receive from her mistress the highest encomiums.

At once progressive in the assumption that former criminals may be rehabilitated, the reformers in the Prisoner’s Friend Association also paint a very clear picture of the limits of that rehabilitation: who it is possible to rehabilitate, and what the former prisoners might be suitably rehabilitated for: the roles of wife and mother, the position of servant.

Researchers interested in the history of prison life, prison policy, and prisoner advocacy are invited to explore our collections to see what other primary sources we have to offer!