By Emilie Haertsch

As the New Year approaches, many people set aside time to reflect upon their lives. What has transpired over the past 12 months? What were our successes? Where could we have improved? Charles Francis Adams, too, used the end of the year as an opportunity to evaluate his life, and the Society has his diary entries on the subject in the Adams Family Papers.

As the New Year approaches, many people set aside time to reflect upon their lives. What has transpired over the past 12 months? What were our successes? Where could we have improved? Charles Francis Adams, too, used the end of the year as an opportunity to evaluate his life, and the Society has his diary entries on the subject in the Adams Family Papers.

Charles Francis was the grandson of John Adams and son of John Quincy Adams. Hoping to carry on the Adams family legacy of public service after the untimely deaths of his two older brothers, he became a politician, writer, and editor. In this December 31, 1852 diary entry he reflects on the previous year, including both the positive and the negative.

And thus terminates the year 1852. I look back upon it with a great many emotions, in which the leading one is gratitude for unnumbered blessings enjoyed. I have lost in it my last earthly parent, but under circumstances which soften the pain I might have felt for the blow. She lives to me in the agreeable recollection of the profuse affection she uniformly bestowed upon me during her life.

Charles Francis’s mother, Louisa Catherine Adams, suffered a stroke and died on May 15, 1852. Adams had other difficulties, as well, that year, but he chose to look on them in a positive light, writing, “These things have been given to me to purify my heart and my mind, and to warn me to correct the defects of my own character and temper.” Adams was 45 years old when he wrote this entry but still concerned with improving himself. He hoped to live up to his own expectations and reach his goals before he reached his dotage.

If only all of our year-end reflections were so generous to others and focused on self-improvement. Perhaps Adams’s words will provide us with a little inspiration. Do you take the time to self-assess at the end of the year? What other New Year’s traditions do you keep? Share with us in the comments below.

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds

Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience.

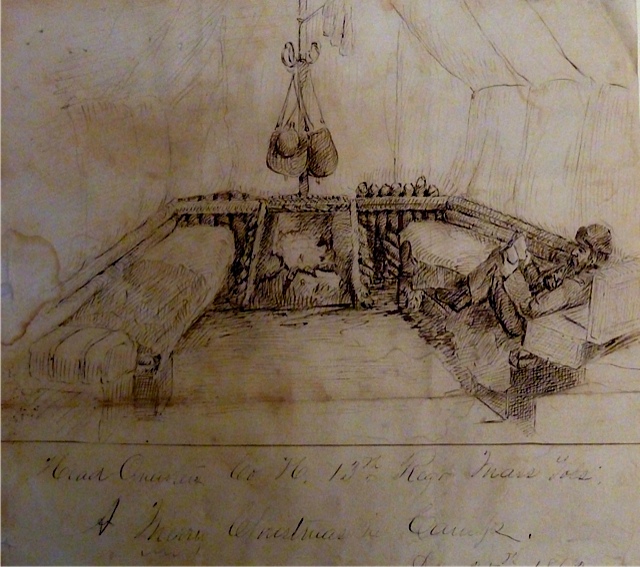

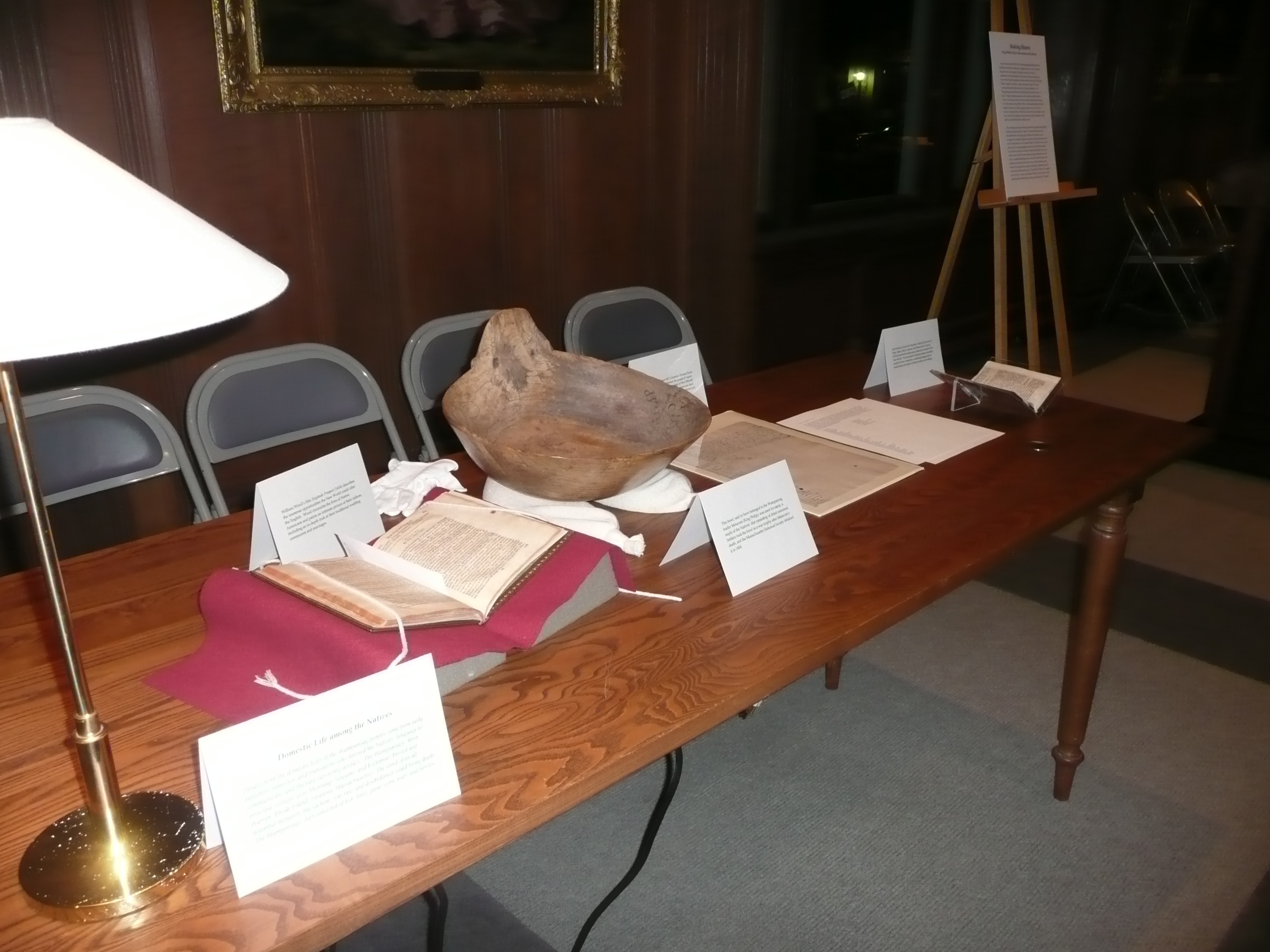

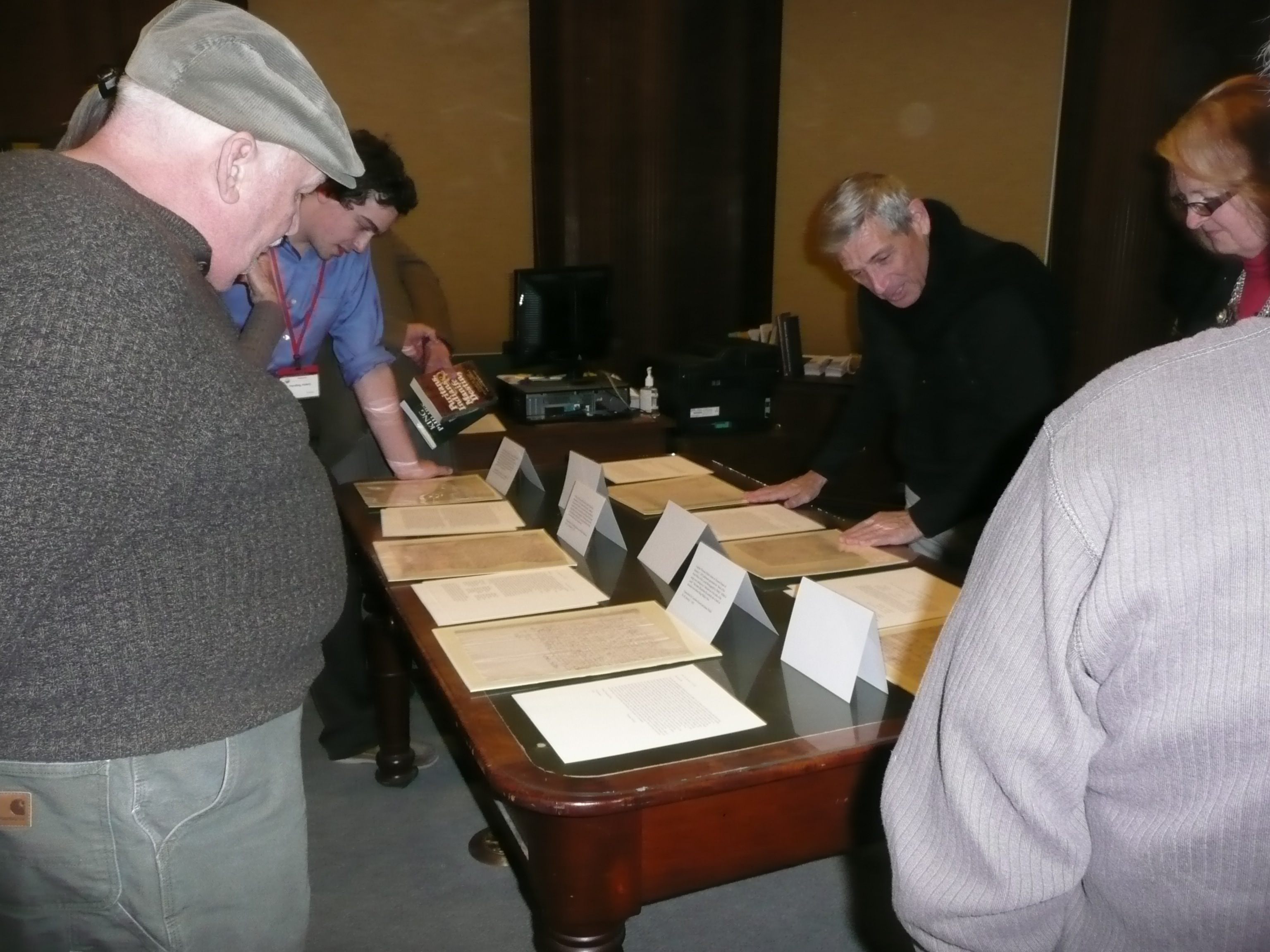

When I eagerly returned home the following day to inspect the brandy infusion, a heavenly citrus aroma wafted from the bowl. I removed the lemon zest from the brandy and added water, lemon juice, and sugar. Because I didn’t exactly have a whole nutmeg lying around (Stop & Shop was fresh out), I had to cheat a bit with that part of the recipe. I substituted the pre-grated spice instead, estimating the amount. I stirred the concoction until the sugar dissolved, but let’s face it – it was still mostly brandy. The temptation to try it then was strong, but I held out for the true Franklin experience. Students visited the MHS several times, both as a class and as individual researchers. They had the opportunity to analyze a series of manuscripts and published documents. Pamphlets such as John Eliot’s Strength Out of Weakness (1652), describe Puritan’s attempts to convert Indians to Christianity, while other works, like William Hubbard’s The Present State of New-England: Being a Narrative of theTroubles with the Indians in New-England (1677) suggest that not all native peoples were willing to adopt English customs or religious principles. Class members also transcribed a number of documents from the Winslow family papers, which include the papers of Edward and Josiah Winslow, colonial governors of Plymouth Colony from 1638-1680. Several letters in the collection detail colonists’attempts to negotiate with Metacom and other native inhabitants, even as native groups began forming alliances against the English settlers.

Students visited the MHS several times, both as a class and as individual researchers. They had the opportunity to analyze a series of manuscripts and published documents. Pamphlets such as John Eliot’s Strength Out of Weakness (1652), describe Puritan’s attempts to convert Indians to Christianity, while other works, like William Hubbard’s The Present State of New-England: Being a Narrative of theTroubles with the Indians in New-England (1677) suggest that not all native peoples were willing to adopt English customs or religious principles. Class members also transcribed a number of documents from the Winslow family papers, which include the papers of Edward and Josiah Winslow, colonial governors of Plymouth Colony from 1638-1680. Several letters in the collection detail colonists’attempts to negotiate with Metacom and other native inhabitants, even as native groups began forming alliances against the English settlers.

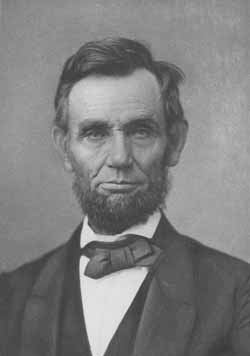

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.