By Jim Connolly, Publications

It’s the most wonderful time of the year: that time when a new volume of the Massachusetts Historical Review goes to press! Print subscribers will receive Volume 14 by mail in the early days of the new year, and the electronic version will be published simultaneously through JSTOR’s Current Scholarship Program. Learn more about subscription here. The journal is also a benefit of MHS membership—learn more about membership here!

The upcoming volume treats a diversity of fascinating topics:

“Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic” by Amalie M. Kass

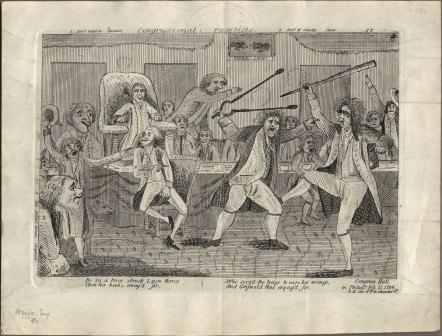

Cotton Mather’s advocacy for inoculation—a practice then unheard of in the colonies—stirred up a controversy in 18th-century Boston. Insults and accusations flew in the partisan newspapers as inoculation’s champions and opponents fought for public health—and personal glory. The source of Mather’s knowledge of inoculation may surprise you.

“The Newbury Prayer Bill Hoax: Devotion and Deception in New England’s Era of Great Awakenings” by Douglas L. Winiarski

This article explores the phenomenon of the prayer bill or prayer note in colonial religious practices, and how a satirical prayer bill was crafted to injure the reputation of Newbury Congregational minister Rev. Christopher Toppan, who vehemently opposed the popular religious revivals of the Great Awakening.

“A Prince among Pretending Free Men: Runaway Slaves in Colonial New England Revisited” by Antonio T. Bly

Bly sheds light on the lives and characteristics of runaway slaves through in-depth analysis and explication of runaway notices in newspapers. Clues within these notices tell us how fugitive slaves employed quick wits and savvy under extraordinary duress. Bly, who has compiled a database of runaway slave notices, crunches the numbers on a variety of characteristics, illuminating the most common months for escape, the race, linguistic ability, and work backgrounds of runaways, and more.

“Boston, the Boston Indian Citizenship Committee, and the Poncas” by Valerie Sherer Mathes

When the Ponca Indians of Nebraska were forced from their homeland in 1877 and sent to the inhospitable Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), many Americans sympathized with their plight. Among those who took up the cause was the Boston Indian Citizenship Committee, a group of philanthropists, described in detail for the first time in this article. Mathes also chronicles the speaking tours in support of the Poncas, including the tour of Ponca chief Standing Bear.

The new volume also includes review articles by Sarah Phillips and Chernoh Sesay concerning environmental history and books about Phillis Wheatley and Venture Smith, respectively.

Every issue of the MHR offers pieces rich in narrative detail and thoughtful analysis, and Volume 14 is no different. The MHS looks forward to its publication.

Friday, 30 November, we close out the month with our signature fundraising event. Tickets are still available for

Friday, 30 November, we close out the month with our signature fundraising event. Tickets are still available for