By Daniel Hinchen

“Never since the clink of the first hammer of civilization that rung its notes upon the tri-mountains of the present town or city of Boston, has there been or is there likely to be, such a gala day as that of the 25th of October, 1848! The entrance and reception of Washington, of Lafayette, and the still greater acclamation, parade and pageant that welcomed ‘Old Hickory,’ the Bunker Hill Celebration, all, all fall far behind the brilliancy, fervor and grandeur of the demonstration mode by the citizens of Boston and country adjacent upon this great occasion—introduction of the waters of Lake Cochituate into our city!”

Such was the joy in Boston and surrounding areas when the new aqueduct was opened in 1848, giving the citizens what they wanted and needed for so long: water that was not only fresh, but free.

While a modern day parade that hails our sports teams as champions draws thousands of loyal fans to the streets, none will celebrate an event that had such an impact on the city or attract such a diverse crowd. While some put their hopes and emotion into supporting the Bruins or the Red Sox and cheer their victories, this was a cause to celebrate lives saved and enriched.

While a modern day parade that hails our sports teams as champions draws thousands of loyal fans to the streets, none will celebrate an event that had such an impact on the city or attract such a diverse crowd. While some put their hopes and emotion into supporting the Bruins or the Red Sox and cheer their victories, this was a cause to celebrate lives saved and enriched.

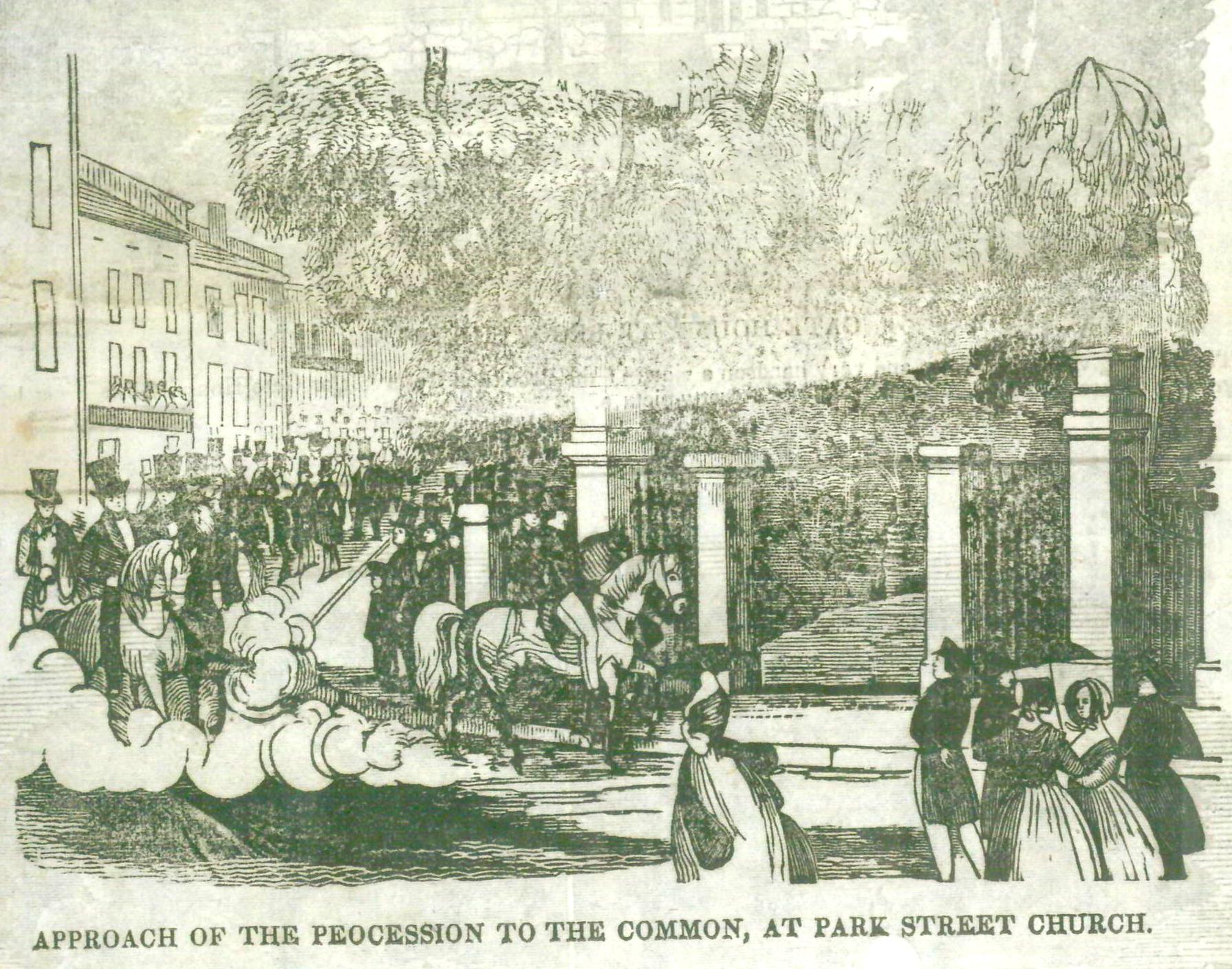

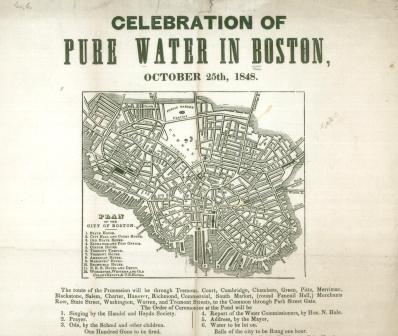

People from all walks and all professions were in attendance. The great procession included, among others: firemen, military, various committee members, Governor Briggs, state officers, municipal authorities, clergy, physicians, mechanics, reporters. There were printers pulling a printing press that spat out flyers and programs as the group proceeded. All of these groups were represented in the first two divisions of the parade, which consisted of at least six divisions! And this does not include the people watching the procession. “We certainly never saw Boston so packed with people before; for miles nothing but compact masses of human beings were to be seen in our streets.”

The procession ended at Boston Common, at which point the performances began. There was singing by the Handel & Haydn Society, a prayer by a reverend minister, an ode sung by schoolchildren and penned by James Russell Lowell. A report on behalf of the Water Commission followed, along with an address by the Mayor. Finally, the water was turned on and the chorus from the Oratorio of Elijah was proclaimed.

The procession ended at Boston Common, at which point the performances began. There was singing by the Handel & Haydn Society, a prayer by a reverend minister, an ode sung by schoolchildren and penned by James Russell Lowell. A report on behalf of the Water Commission followed, along with an address by the Mayor. Finally, the water was turned on and the chorus from the Oratorio of Elijah was proclaimed.

Thinking of this event serves as a reminder of the major steps that a city like Boston takes in its development, and that the running water that is now taken for granted was once cause for unparalleled festivities, celebration, and joy.

To learn more about the celebration, or the struggle to bring additional clean water into Boston in the 19th century, visit the MHS library to discover additional source materials.